1907 (Sample Chapter)

A note to readers: This is a first draft of the 1907 chapter proposed for the book. By the time the book appears it may be much altered.

There weren’t many automobiles in Vancouver in 1907 (a five-minute film taken along several downtown streets this year shows precisely one), but there were enough for someone in the Vancouver office of the Imperial Oil Co. to decide that the usual method of fueling them at the time—carrying a sloshing bucket full of gasoline up to the vehicle and pouring it through a funnel into the tank—was somewhat dangerous. So, adjacent to Imperial’s storage yard at the southeast corner of Cambie and Smithe, the manager of the company’s Vancouver office, Charles Rolston, built a small open-sided shed of corrugated iron. Atop a tapering concrete pillar he placed a 13-gallon kitchen hot-water tank “fitted with a glass steam-gauge marked off by white dots in one-gallon increments.” The tank was gravity fed, being connected to Imperial’s main storage tank.

The filling hose was a ten-foot length of garden hose, drained with thumb and finger by the attendant after filling a car. The first attendant was Imperial’s former night watchman, J.C. Rollston (no relation to Charles Rolston), who had been in poor health. His coworkers believed he would improve in the sun and open air. Future city archivist J.S. Matthews, who worked for Imperial Oil at the time, said “We got a barroom chair, and my wife made a cushion for it.” A corrugated tin shed was built for shelter and Rollston was installed as attendant.

Canada’s first gas station was now in business. “The fresh air and the sunshine soon banished the pallor from Mr. Rollston’s cheeks,” Matthews recalled. “And, ofttimes as I passed and waved good morning, he would call out, ‘I’ve been busy this morning!’ ‘How many?’ I would call, and he would answer back, ‘Three cars this morning!’” The first gasoline-powered car in Vancouver had arrived in 1904, so sales must have been slow at first! Two local bicycle shops began selling gasoline, which they bought from Imperial for 20 cents a gallon and sold for 40.

Word of this way of delivering gasoline to cars spread. “A dealer in Florida,” says Matthews, “wrote asking details.” (The Florida people had been using garden watering-cans.) It’s sometimes claimed this was the world’s first gas station. It’s not, but it was certainly Canada’s first. That humble kitchen hot-water tank is still around, tucked into a basement corner in the Vancouver Museum.

A 1907 movie

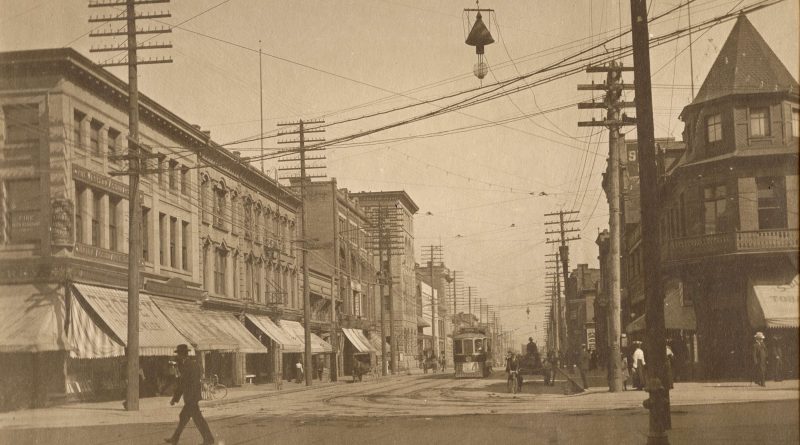

The Vancouver of 1907 was a thriving, energetic city. The population was climbing rapidly, jumping from 27,000 in the 1901 census to the 70,000 of 1907. We can actually see the city’s vitality thanks to a man named William Harbeck who set up a film camera at the front of a BC Electric Railway streetcar and on May 7 filmed the city’s downtown streets.

This is the earliest surviving film on Vancouver. Its discovery was something of a miracle: it was found in the basement of an abandoned theatre in Sydney, Australia! It had apparently been dumped there by movie house managers along with other movies no longer wanted. Some pieces are missing, and the entire film is just five minutes long, but those five minutes are valuable.

It is fun and exciting to see streets full of horse-drawn wagons, men (every one of them wearing a hat) strolling into long-gone shops, women hurrying along in their dark, ground-length skirts, bicyclists speeding by, and the occasional recognizable sign: Knowlton Drugs; P. Burns (meat packer); the Edison Grand Theatre; Woodward’s, and “Cascade: A Beer Without Peer.” We see the now-vanished second CPR station at the foot of Granville, Trorey’s Jewelry and the original Vancouver Daily Province newspaper building. (In reporting on the filming the Province said the people of the city had been stricken with “kinetoscopitis.”) We travel along Granville and Hastings, along Westminster Avenue (now Main Street) and Carrall, Powell, Cordova and Cambie, Robson and Davie . . . a unique look at a Vancouver of a century ago.

The streets are alive with people. We see in these flickering, silent images a city that has almost tripled its population in six years.

Lots going on

The city’s major newspaper, the Province (five cents, please) had a circulation of just over 15,000. (The Vancouver Sun was still five years away.) In the Province’s pages you find ample evidence of the economic and social ferment Vancouver was enjoying.

Some examples:

- The Montreal-based jeweler, Henry Birks & Sons, came to Vancouver in February of this year and bought the well-established shop of George Trorey, at the northeast corner of Granville and Hastings. They kept Trorey on as manager—and they kept his famous sidewalk clock, too. The Birks clock and the store can just be glimpsed as our movie-streetcar swings east onto Hastings from Granville. The clock is plainly visible in the photograph at the top of this page.

- David Spencer, who had earlier (1873) started a store in Victoria, put his son Chris, 38, in charge of a big new Spencer’s on Hastings Street in Vancouver. Chris had started working for the Victoria store in 1882 at age 13. The new store was so successful that it eventually took up almost an entire city block. Today, the building is SFU’s downtown campus.

- There were enough cars in Victoria to justify the establishment there of a new organization, the British Columbia Automobile Association. They would get to Vancouver in 1908.

- Just a few months after Harbeck’s May filming, the Vancouver Police Department bought its first automobile. The car got its first use in August when one Richard Goddlander, “a well-known police character,” was charged with public intoxication and given his first automobile ride. Destination: the city jail. We have a hunch Richard would have been quite excited—if he noticed.

- The chief of the Vancouver Fire Department, John Howe Carlisle, arranged to have three motorized firefighting units purchased this year, in the face of some amused, some not-so-amused, opposition. The company making these units—Seagrave of Columbus, Ohio—had just begun their manufacture, and very few fire departments in North America were making the switch, preferring to stick with horses. Vancouver’s motorized equipment was the first in Canada. “I think Carlisle was persuaded to go motorized,” VFD historian Alex Matches said, “because he was one of the first people in Vancouver to own an automobile. It was a two-cylinder McLaughlin-Buick touring car, and Carlisle was impressed with how quickly he could get around in it.”

- The Vancouver Stock Exchange was incorporated April 12, a month before this movie was made. The exchange, headquartered at 849 West Pender, had 12 charter members. Said the president, C.D. Rand: “Many applications to list stocks of doubtful merit have already been made to the Exchange, but have been promptly turned down by your executive, and this policy will be adhered to while we remain in office.” That would change!

- On May 11, the University Women’s Club of Vancouver was founded by eight graduates. The club thrives to this day. (The Stock Exchange doesn’t.) One of the club’s founding members was journalist Lily Laverock, whose future fame in the city would be of a much different kind.

- A dozen Vancouver businessmen formed the Vancouver Exhibition Association, with a goal of developing a fair to showcase Vancouver to the world. They succeeded, and beginning in 1910 the Pacific National Exhibition would become an annual tradition.

- The most famous writer in the world at the time, Rudyard Kipling, visited Vancouver again. Kipling really liked this city; this was his third visit, and he even bought land here (at the southeast corner of East 11th Avenue and Fraser Street.)

- W.J. Timmins, proprietor of the Pantages vaudeville theatre on Hastings Street, was up from Tacoma to “look over the work.” This little jewel of a theatre opened January 6, 1908. It’s still there at 152 East Hastings, the oldest theatre in Greater Vancouver, the oldest remaining Pantages theatre in North America, and one of the oldest purpose-built vaudeville theatre interiors in Canada. The theatre—whose architect was Edward Evans Blackmore—was being eyed in 2006 by a consortium of local theatre people who hoped to restore it to its original use.

In a February, 1949 article in the Province Patrick Keatley says that Alexander Pantages preceded the East Hastings establishment with a theatre in a rented store on Powell Street. (There would be another Pantages Theatre built in Vancouver in 1914, a 1,200-seat palace of entertainment. It was torn down in the 1970s for a parking lot.)

Of course, there was crime news, too. Richard Goddlander’s beer-soaked ride paled into insignificance compared to the escape of train robber Bill Miner, the ‘Grey Fox,’ from the penitentiary in New Westminster. And the Vancouver of a century ago could be a tough and intolerant place: an Asiatic Exclusion League was formed to keep Oriental immigrants out of B.C. The League was behind raids September 7 in Vancouver’s Chinatown and Japantown that would bring shame to the city.

Riots and Racism

The Vancouver Sun Magazine in a 1947 issue looked back at that event in an article by Albert Foote: “A monster parade marched down Hastings Street that night. First came the speakers and their lady sympathizers in horse-drawn carriages, followed by over 5,000 marching men, each with a white badge fluttering from his buttonhole . . . Then someone shouted ‘On to Chinatown!’ and the trouble started . . . On the first trip only rocks were thrown and hundreds of windows were broken. The second trip proved more vicious, for this time there was gunfire. When the mob grew tired of this they moved down to Japtown. Here they met fierce resistance but there was no shooting . . . No Chinese or Japanese appeared on the streets for days. The Oriental sections of Vancouver were roped off by the police and remained under martial law for ten days.”

Two days later the Province reported “The Chinese of Vancouver armed themselves this morning as soon as the gun stores opened. Hundreds of revolvers and thousands of rounds of ammunition were passed over the counter to the Celestials before the police stepped in and requested that no further sale be made to Orientals . . . Few Japanese were seen buying arms, but a bird’s-eye view today of the roofs of Japanese boarding-houses and stores in the Japanese district disclosed the fact that the Orientals are prepared for a siege. Hundreds of bottles are stored on the roofs, and these with stones, clubs, and bricks will be hurled at the whites in the streets below should any further trouble occur.”

Ironically, later in the year the city would play host to a visit from His Imperial Highness Prince Fushimi of Japan.

When the federal Deputy Minister of Labour visited Vancouver to review damage caused by the anti-Oriental riots, he was dismayed to learn the manufacture and sale of opium here were legal. To a man possessed of the moral rectitude of William Lyon Mackenzie King, this was an intolerable situation. When he got back to Ottawa he initiated a federal ban on the sale of opium—but in Chinese-run establishments only.

At one point in the Harbeck film the streetcar rattles by 570 Granville Street. Up on the second floor of this building, an artist named Miss Emily Carr had a studio. Who knows, maybe she looked out her window (if she faced the street) as movie-maker Harbeck passed. Tragically, when the Titanic sank in 1912 William Harbeck was one of the hundreds who went down with her.

A new weekly publication called Saturday Sunset started in June. Its stance on local race relations is indicated by a cartoon it published in an early issue: one panel, titled ‘Typical Home of Vancouver white workingman,” shows a pleasant Victorian home with the man of the house coming home from work to be met by his adoring wife and children. In the other panel is a long low two-storey apartment block titled ‘A warren on Carrall Street infested by 2000 Chinese.” Next to the white man’s house is a drawing of a little girl skipping rope. Next to the ‘warren’ is a drawing of a Chinese man sucking on an opium pipe.

Cultural doings, etc.

Vancouverites were singing new songs in 1907: It’s Delightful to be Married and Dark Eyes and On the Road to Mandalay (with lyrics by Rudyard Kipling), and Harrigan by George M. Cohan (“H-A-double R-I . . .”), humming a tune called The Teddy Bear’s Picnic and reading a new book, Songs of a Sourdough by Robert Service, including The Cremation of Sam McGee and The Shooting of Dan McGrew. George Eliot’s novel Adam Bede, written nearly 50 years earlier, was being serialized—in great swaths of tiny print—in the Province.

A fellow named Richard Cormon Purdy opened a shop on Robson Street and began selling chocolates.

The tiny Arbutus Grocery at the corner of West 6th Avenue and Arbutus Street was built in 1907 by Thomas Frazer. A century later it’s still there, with its “boomtown” facade and an unusual corner entry. And construction started this year on a rather grander building with General Alexander Duncan McRae’s “Hycroft.” The general, who was newly arrived from Ontario, took advantage of Hycroft’s location on a high point of land to ensure that his stately Shaughnessy mansion, unlike most of the others in that lavish neighborhood, would have a good view of the north shore mountains. The house would take five years to complete, and cost more than $300,000 at a time when $3,500 would put you into a fine house.

A drawing of the proposed Dominion Building was given May 4 in the Province. The finished design would be slightly different, but it’s obviously that famous red-and-tan building, called “Vancouver’s first skyscraper,” at the northwest corner of Cambie and Hastings. It would open for business in 1910.

Over on the north shore the map changed. On May 13 the small, central core of North Vancouver’s business and industry broke away and formed its own municipality, the City of North Vancouver. The residents felt their area would be more prosperous on its own. The District was deprived of its water system, municipal hall, ferry terminal and ferry, fire-fighting and road-making equipment, even its cemetery. In return the new City paid some outstanding liabilities of the District. A May 4th article in the Province had described the new town as a “City of Splendid Possibilities.”

The Province was also the newspaper that complained in its editorial pages (in June) that Seattle had a “spieler” in an open streetcar who took visitors around the city pointing out the sights. “Why don’t we?” the paper asked. Not until 1909 would the BC Electric follow that lead. More traditional rail travel emerged when the Great Northern Railway, an American firm, started construction of a line that followed a coastal route from Blaine, around the Semiahmoo Peninsula and across the Fraser River to New Westminster. When service started March 15, 1909, settlers were finally able to arrive in numbers.

City council was discussing street names on September 30, and decided to commemorate famous battles. So what had been Campbell Street became Alma Road (Crimean War), Richards Street became Balaclava (also a Crimean War battlesite), Cornwall, the second street with that name, became Blenheim to recall the Battle of Blenheim, Lansdowne became Waterloo, and the old Boundary Street on the west side that divided District Lot 192 and the CPR grant became Trafalgar.

Image: Corner of Hastings and Granville St., Vancouver, 1907 [City of Vancouver Archives]