1929 (Sample Chapter)

A note to readers: This is a first draft of the 1929 chapter proposed for the book. It was completed March 20, 2006. By the time the book appears in 2009 it may be much altered.

The big story in 1929 for Vancouver was not the Great Depression. The first ominous effects of the crash would begin to be felt by the end of the year, but we wouldn’t begin to feel the real effects until 1930. No, for Vancouver in 1929 it was an explosion in size. On January 1st the amalgamation of Point Grey and South Vancouver came into legal effect, and overnight Vancouver—the southern boundary of which had been 16th Avenue—became Canada’s third largest city. The new population: 240,000. It had been 117,000 at the 1921 census.

The first mayor of the larger city—he’d defeated the incumbent, L.D. Taylor, the previous November—was W.H. Malkin, whose name since 1896 had been most visible on the labels of the jams and jellies his company packed. At the first meeting of the new city council January 2nd Malkin paid a gracious tribute to Taylor, giving him credit for the work he had done in pushing for the amalgamation.

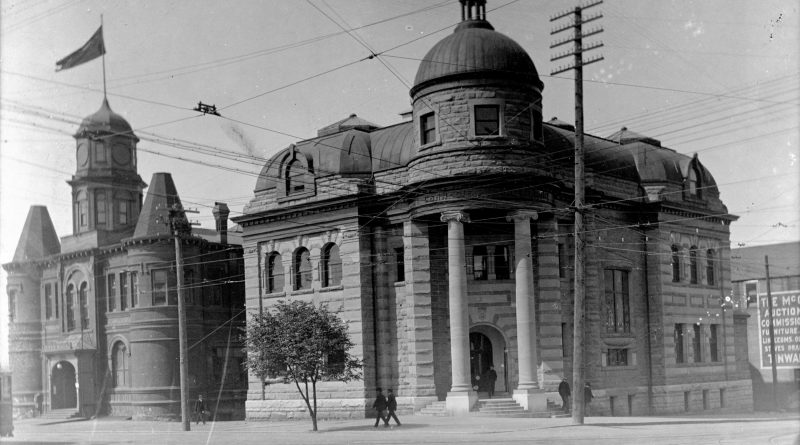

A bigger city needed a bigger city hall. Since 1897 a sombre, dark red, somewhat dumpy building immediately south of the Carnegie Library on the west side of Main Street had served as city hall. It had once been a public market, later an auditorium. Now a move was made from that overcrowded place into the Holden Building at 10 East Hastings. This handsome ten-storey structure would serve as city hall until the present one opened in 1936. (Later, in May, 1929 Vancouver voters would approve 14 of 20 money bylaws presented to them, but reject a new city hall, so the ‘temporary’ Holden Building served much longer than had been planned.)

In June the old red building would become an annex to the adjacent library.

The school population of Vancouver also grew, of course: to its existing 22,000 students were added nearly 9,000 pupils from South Vancouver and more than 6,000 from Point Grey.

Building, building, building . . .

A great deal of building went on in Vancouver in 1929, highlighted March 13 when Mayor Malkin blew a blast from a golden whistle, setting in motion a steam shovel that began an excavation for the construction of the Marine Building. This 25-storey beauty, designed by the architectural firm of McCarter & Nairne—who became one of its charter tenants—and built by E.J. Ryan Contracting, would open in 1930. Read more about it in that chapter.

The Georgia Medical-Dental Building, the first art deco-style building erected in Vancouver, went up this year at the northwest corner of Georgia and Hornby Streets. It was richly embellished with whimsical ornaments like plump little terra cotta owls and other birds, lions and horses. The building was adorned with medical, religious and mythological symbols around the main door. Most of its tenants were doctors, dentists and the like. Easily the most famous distinguishing features on the building were three 11-foot-high terra cotta statues of nursing sisters in First World War uniforms, one perched on each of the building’s three visible corners. A local gag—inspired by the medical use of the building—was that they were the three Rhea sisters: Gono, Dia and Pyo. The building was designed by McCarter and Nairne, whose more famous Marine Building would soon follow. Sixty years after its opening the dignified old structure would be demolished—Sunday, May 28, 1989—by a controlled explosion (viewed by a huge throng in the surrounding streets), following an intense but unsuccessful public campaign to save it. Replicas of the nurses can be seen at Joe Tinucci’s Ital Decor location at 6886 East Hastings Street.

Another city landmark, the Royal Bank building at the northeast corner of Hastings and Granville, edged into print this year: on June 17 the Journal of Commerce reported that tenders had been called by the Royal Bank for the property. That famous corner had been occupied for many years, first by jeweler George Trorey, then in February 1907 by Birks. The Journal also reported that the Bank of Nova Scotia would build a new branch at the northeast corner of Granville and Davie Streets. Today that building is Vancouver’s Dance Centre. In June the Sun told us that the proposed ‘Canadian National Hotel,’ the present Hotel Vancouver, would be expanded. One hundred extra rooms would be added, and the hotel would be 16 storeys high. Several such reports would appear during the hotel’s construction. It kept getting bigger and bigger—on paper. Then the Depression came along.

Given the construction or impending construction of all these lofty buildings, here’s a curiosity: on October 25 the Province wrote: “Vancouver will have no skyscrapers if the City Council accepts the advice of its Town Planning Commission . . . This morning the commission again endorsed the provision of the city charter which requires all buildings to be within ten storeys in height or 120 feet.”

The Randall Building, in the 500 block West Georgia, was built this year. Since being rehabilitated in 1991, it’s now known as the Cavelti Building, after jeweller Toni Cavelti. The Dick Building, an ornately decorated structure at the southeast corner of Granville and Broadway, and the equally ornate Bank of Commerce at 817-819 Granville are also from 1929. All three are heritage buildings today, preserved for their aesthetic and architectural value.

On June 1st an artist’s conception of the new Stock Exchange Building in Vancouver appeared in the Sun. The building, the second of that name, would be at the northwest corner of Pender and Howe Streets. What an unpleasant surprise they have coming in about five months!

Out at UBC the Union College Library was okayed in May. The Anglican Theological College opened October 1st, and the university’s first gymnasium, built with funds raised by students, finally provided a proper place for the sports-minded among them to play. Built when the number of students was about 1,500 it would eventually prove too small. Still, it would serve until the War Memorial Gym opened in October of 1951. The 1929 gym stood where the Buchanan Tower is today.

Point Grey Secondary School opened at 5350 East Boulevard in Kerrisdale.

Boeing of Canada opened a plant on Coal Harbour this year. It had been the Hoffar-Beeching Shipyard at 1927 West Georgia; in 1930 Boeing would begin to build seaplanes there.

Construction began on the East Lawn Building at Essondale (now Riverview) Hospital.

More building!

The Commodore Cabaret opened December 3rd on Granville Street. Owners Nick Kogas and John Dillias began a tradition of showcasing local bands and international touring artists, and the place—known today as the Commodore Ballroom—is still bringing in big names in music.

Members of the Cambrian Society, named after the Cambrian Hills in Wales, built a community hall at 215 East 17th Avenue. Wrote Kevin Griffin, in The Greater Vancouver Book, “This is believed to be the only hall built and operated by a Welsh society in North America . . . [The] hall became the home of the annual Eisteddfod, a competitive singing and reciting festival, and the Gymanfa Ganu, a hymn singing festival.” The Hall was officially opened September 1st by Marion Malkin, the mayor’s wife. Today’s Welsh Society tells us that “the cornerstone at the front of the Cambrian Hall pays tribute to the members of the Cambrian Society (as the Welsh Society was then known) who were donors to the building fund and also to those who had assisted in erecting the building. Among the donors were prominent Vancouver citizens, such as Chris T. A. Spencer, a member of the Spencer’s Department Store family, Thomas Edwards, a leading Vancouver businessman, and Jonathan Rogers from the Ceiriog Valley, a builder and philanthropist who spent 26 years serving on the Vancouver Parks board. The land on which the Hall is situated was sold to the Society for one dollar by Joseph Jones from Prestatyn, the owner of a Vancouver dairy and a long-term school trustee.”

The intense building activity in the city persuaded city leaders that some sort of direction was needed. That had prompted the formation in 1926 of the Vancouver Town Planning Commission, marking the beginning of formal planning efforts in the city. In 1928 the Commission hired Harland Bartholomew and Associates, a town planning firm from St. Louis, Missouri which had designed city plans for many cities across the United States. On December 28 of this year Bartholomew submitted his report—which had been modified by the amalgamation with Point Grey and South Vancouver. The plan was ambitious. His team had surveyed the city, prepared detailed reports on zoning regulations, street design, transportation and transit, public recreation and civic art. They planned for a city of one million people focused on the “great seaport” of Burrard Inlet. The Fraser River banks and False Creek would be industrial. Businesses would spread evenly over the central business district to “prevent undue traffic congestion.” The West End would provide apartments close to jobs. “The Bartholomew Plan,” city planner Dr. Ann McAfee wrote in The Greater Vancouver Book, “was never formally adopted by City Council. Nevertheless, over the years, much of Bartholomew’s vision was realized.” The most well-known visible evidence today is the central boulevard down Cambie Street, south of King Edward.

Involved in all of this was J. Alexander (Sandy) Walker, who began this year what would become a long stretch as Vancouver’s town planning engineer. He would serve to 1952. The City of Vancouver Archives has a hand-written letter to Walker, written October 4 this year. Carefully inscribed, it came from Lauchlan Hamilton, the man who had laid out most of the city’s downtown streets more than 40 years earlier. Hamilton, 77 at the time he wrote the letter, had been the CPR’s land commissioner here. He was re-visiting the city.

“I cannot say that I am proud of the original planning of Vancouver,” he writes, after explaining that the shortness of his visit precludes a personal meeting with Walker. “The work, however, was beset with many difficulties. The dense forest, the inlets on the north and False Creek on the south, the pinching in of the land at Carrall Street . . .” and so on, and so on.

If you look at a map of Vancouver, you’ll note that east-west streets crossing Burrard often do not line up. In his letter to Walker, Hamilton complains of a severe problem. His “original plan” for the streets in the city’s downtown peninsula had to be altered. It seems a property owner named Pratt refused to go along with Hamilton’s design. Local historian John Atkin explains: “Pratt was one of the large land owners in the West End who refused to allow Hamilton to replot the area, hence almost all of the streets going east-west across Burrard don’t match up. Hamilton was quite angry about this. The West End streets were drawn up on a plan and registered in the 1870s, but were never surveyed on the ground. Hamilton had to fit his work to the registered plan, which is why the lot sizes in that area are so odd.”

The Archives has a collection of field survey books used by Hamilton and those working for him. It’s fascinating to leaf through those brittle, yellowing pages and see the pencilled notes and drawings made more than 120 years ago as the surveyors decide to cut a “Granville Street” through here and a “Nelson Street” through there. The pages are covered with scribbled computations and little memos, each street plan carefully dated: the survey of Granville south of Nelson, for example, began March 15, 1885. The corner of Cambie and Hastings was laid out on April 30, 1886. If you’re a surveyor or interested in the subject and you haven’t seen these little books, by all means visit the Archives and ask to have a look.

Not all the building in Vancouver this year was ‘important.’ To the delight of local kids, the Pacific National Exhibition opened its first permanent amusement park, with rides and games. It was near the race track and was dubbed ‘Happyland.’ It would last to the end of the 1957 season, then be replaced by the bigger ‘Playland.’

In June it was announced that Kingsway between Knight and Broadway was to be widened from 66 feet to 99. And there was a name change for a well-known building at the eastern end of False Creek. Known as Union Station from 1917 to 1928—housing the Great Northern and the Canadian Northern Pacific Railway, a precursor to the CNR—it became the Great Northern Station. The building would be demolished in 1965.

Over in North Vancouver, the North Shore Hospital opened May 30, and on June 28 bids were called for a bridge over the Capilano River in West Vancouver.

Can You Hear Me Now?

The GN/CN station just cited was home to radio station CNRV, one of a network of stations CN had set up across the country for its passengers. Radio was still young, and the city—if the city directory is to be believed—had just seven stations (there are 19 today), and some of those were on for just a few hours a day. Besides CNRV they included:

CHLS Province Commercial, 198 West Hastings

CJOR Commercial Broadcasting Service, 212-1040 West Georgia

CKCD Vancouver Daily Province, 198 West Hastings

CKFC Radio Station, West 12th Avenue at Hemlock

CKMO Sprott Shaw 336 West Hastings, and

CKWX Sparks Co., 801 West Georgia

One of the local broadcasting phenomena of those early years was a fellow at CKCD named Earle Kelly, 50, a night editor at the Province. Chosen for his authoritative voice and crisp enunciation he began broadcasting newscasts this year for the newspaper’s station, CKCD, and became known as “Mr. Good Evening” for his lugubrious introduction to those programs. (He never identified himself on these broadcasts.) Kelly, born Michael Aloysius Kelly to Irish parents in Australia, became known as Canada’s first personality broadcaster. He would carry on his broadcasts seven nights a week for 17 years and become famous throughout western Canada. “Mr. Good-Evening,” radio researcher Gordon Lansdell has written, “was a dashing and debonair bachelor, well over six feet tall, who lived at an exclusive businessman’s club on the Vancouver waterfront. On Saturday nights he always delivered his newscasts wearing impeccable evening dress, his white mustache bristling and his hair brushed sleekly back. On his own time, he was often seen playing strenuous games of tennis in nearby Stanley Park or dancing in white tie and tails at the elegant downtown Commodore Cabaret.

“He used the editorial ‘we’ or ‘us’ in most of his broadcasts, to the extent that it crept into his private life and he almost became a plural entity. ‘Excuse us,’ he would say if he coughed on the air. Every night he wound down his newscast with good wishes to the elderly, but only those celebrating birthdays over 90 or anniversaries over 50. Finally, he would, ‘Wish all our listeners, on land, on the water, in the air, in the woods, in the mines, in lighthouses, and especially [a salute to different groups each evening], a restful evening. Good night.’ One night he wished a good night to ‘the Ladies of the Evening’ which brought him a great deal of critical mail from his more sedate audience.”

Vancouver Day

On June 13, 1929 Vancouver marked ‘Vancouver Day,’ but this would be the last time. Back in 1925 city council had named June 13 as Vancouver Day—a time of remembrance and thanksgiving, inspired by the Great Fire of June 13, 1886—and it was arranged that each year as a part of the Vancouver Day ceremonies there would be held, “on the Sunday closest to the anniversary of the fire, a service in Stanley Park . . .” At the ceremony this year a band played a march especially written for the event by Lt. E.J. Cornfield. The tradition was short-lived: this 1929 event seems to be the last time ‘Vancouver Day’ occurred. A guess is that the Depression killed it off. (City archives worker Donna Jean McKinnon and others revived it unofficially for one occasion in the 1990s.)

Getting Around

1929 brought changes in the transportation future of Vancouver. Charles Lindbergh had sparked intense interest in air travel with his 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic. In July of this year he was touring the U.S., speaking in various cities, and when he got to Seattle a Province reporter asked him if he would consider coming up to Vancouver. Lindbergh said no. “Your airport isn’t fit to land on,” he said. That embarrassed Vancouver, and prompted the push to build one that was! It would open in 1931.

And, still up in the air, some local histories indicate that the Graf Zeppelin, the most famous airship of the 1920s, visited Vancouver—specifically, Coal Harbour—on August 27, 1929. Alas, a closer examination of papers of the day revealed the truth: she never got here. “Plans of Dr. Hugo Eckener to bring the Graf Zeppelin over Vancouver and Seattle,” the Province reported, “were upset by two occurrences. Dense fog in the North Pacific forced the airship south in order to get her bearings, and a slight attack of ptomaine poisoning caused the commander to hasten to Los Angeles.” The huge airship had just completed “one of the most spectacular flights of all time, a non-stop 5,800 miles across the Pacific Ocean from Japan . . .”

Down on the ground, the Canadian Pacific Railway began having ‘Hudson’ type steam locomotives built this year by the Montreal Locomotive Works Company. One of them is B.C.’s well-known Royal Hudson. Before production halted in 1940 MLW built 65 of these powerful and marvellously fast engines. The last model produced had a top speed of more than 144 kilometres per hour. They would not get the ‘Royal’ designation, by the way, for another 10 years, when King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother) rode in them across the country.

The long-sought-after Pacific Highway neared approval, and Canada and the State of Washington agreed this year to place the proposed highway and the port of entry near the Peace Arch, erected in 1921—a rare, perhaps unique, example of a major highway being placed to provide access to a public memorial. The Douglas crossing is now used by millions of cars annually.

Out on the water the Taconite, a luxury yacht, was built for William Boeing. She was all teak and 125 feet in length. The Taconite was built at the Hoffar-Beeching Shipyard, adjacent to the Boeing aircraft plant on Coal Harbour. (She’s still in Vancouver, still looks beautiful, and is used for charters.) The West Vancouver ferry system, once a drag on the city’s finances, was now thriving . . . and would continue to do so until the Lions Gate Bridge was opened.

Most importantly, on December 17, 1929 the Empress of Japan II was launched in Glasgow. She would begin service on the Pacific August 30, 1930. This famous liner was fast, with a top speed of 23 knots: in 1931 she would set the pre-Second World War speed record for a Pacific crossing from Yokohama to Victoria of seven days, 20 hours and 16 minutes. Unfortunately, the Depression would impact badly on both passenger and cargo numbers for the Empress line and the service would end in a few years. (After the war with Japan began her name was changed—albeit somewhat belatedly, on October 16, 1942—to Empress of Scotland.)

Entertainment

Colored motion pictures (without artificial tinting) were shown for the first time in 1929 in Vancouver at Kodak’s store on Granville Street. On June 3 the Orpheum Theatre (the present one) ran an ad for a new Mary Pickford film: Coquette, “her first 100% Talking Picture, and the usual big bill of Radio-Keith-Orpheum Vaudeville.” The theatre was now called the RKO Orpheum. Vaudeville, incidentally, was on the way out. It was drawing smaller audiences all across North America. On September 1st the operation of the Orpheum began to be shared by former competitors Orpheum Circuit and Famous Players, and by 1931 the theatre would begin to show movies only. (Vaudeville would still be enjoyed for a few more years in Vancouver, mainly at the Beacon Theatre, but its glory days were over.)

Still with entertainment, it’s not local, but irresistible: 1929 is the year the “Oscars” began in Hollywood.

George Godwin’s acclaimed novel The Eternal Forest under Western Skies, set in Whonnock, appeared. It would be reissued in 1994 by Godwin Books as The Eternal Forest. A British-born Province staff writer named Lukin Johnston gave us an illustrated book titled Beyond the Rockies: Three Thousand Miles By Trail and Canoe Through Little-Known British Columbia. A review says: “he had opportunity to travel widely the province of British Columbia and write about its beauty and character. He used his newspaper material as basis for this book, a snapshot of a beautiful province, the way it was before the outbreak of the Second World War. He later returned to England.” The provincial Public Library Commission this year applied for, and received, a grant of $100,000 from the Carnegie Corporation to test an idea for five years: providing library services to a rural population. The result, still active: the Fraser Valley Public Library.

In sports, Davey Black, the club pro at the Shaughnessy Golf Club, teamed with Duncan Sutherland to beat world-famous Walter Hagen and Horton Smith at the Point Grey Golf Club. On August 7th the first annual B.C. High Schools Olympiad opened at Hastings Park. This is the year the Tyee Ski Club was formed on Grouse Mountain, making it one of the oldest ski clubs in Canada. By the mid-1930s, the mountain had its first rope tow. Since then, organized skiing and ski racing have flourished at Grouse. The Alpine Club of Canada conducted a ski tour of Mount Seymour this year, and vigorous development followed. Out on the water, the Lady Van, a racing yacht affiliated with the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club, won the 1929 Lipton Cup, defeating a Seattle crew.

Business

In business news, on March 12 the Vancouver Board of Trade chose W.C. Woodward by acclamation as its president for the following year. A couple of months later newspapers reported that the Board of Trade was prominent among the bodies pushing for a Commerce faculty at UBC. They got it.

A US-based chain of grocery stores, Safeway, arrived in Canada this year, just three years after its 1926 birth. The major grocery chain in Vancouver in 1929 was another US-based company, Piggly Wiggly, which had 28 locations in the city. Safeway would eventually take over the Piggly Wiggly chain.

Ben Wosk, future furniture merchant, born March 19, 1913 in Vradiavka, Russia, arrived in Vancouver with his family in 1929. London, England-born William George Murrin, who had joined the B.C. Electric Railway in 1913 as mechanical superintendent, became president this year. He would hold that office until 1946. James M. McGavin became president of McGavin Bakeries, and he would hold that title until his retirement in 1947. And it was reported in June that Jones Tent & Awning had just started to manufacture, for the first time in Canada, Venetian blinds.

As an indication of the growing importance of visitor dollars the Vancouver Publicity Bureau (precursor to Tourism Vancouver) announced that “money expended to advertise the tourist attractions of the city brought better returns than that expended on advertising for new industries.”

The White Rock area of Surrey (then still a part of Surrey) experienced a financial setback when the local lumber mill closed because of a log shortage. And there was trouble on the water: in 1922 fishing licences to “other than white, British subjects and Indians” had been cut by up to 40 per cent. Local Japanese fishermen took their case to court and won, but the provincial government enacted legislation to allow the discrimination to continue. The case went to the Privy Council in England this year. The fishermen won, but only half of them were still around by the time the decision was handed down.

Located at 140th Street and 96th Avenue in Surrey, the 640 acres of Green Timbers have become a memorial to what once was a larger natural forest of giant evergreens soaring to 200 feet and more in height. Writes Terri Clark of the Vancouver Parks Board in The Greater Vancouver Book, “Green Timbers was, at the turn of the century, the only remaining stretch of virgin forest between San Diego and Vancouver. Tourists would come from all over to view these cathedral-like groves in a 5,000-acre refuge. Despite proposals to have the forest declared a park, Green Timbers was clear-cut in 1929, the entire population of trees lost to feed a local sawmill.”

For business the year ended horribly. In late October the New York Stock Exchange collapsed and launched a severe economic crisis in the USA. Canada and the rest of the Western world would not be immune. The Great Depression had begun. Volume on the Vancouver Stock Exchange was 143 million shares this year, would drop to 10 million in 1930. But, again, except for people directly involved in the market 1929 itself did not seem that ominous. For those who were involved, it was a different story. Vancouver accountant Pat Dunn recalls: “I got a position with the brokerage firm Branson, Brown and Company on October 23, 1929, the day of the great financial crash. Branson, Brown and Company was the largest brokerage firm in town and was a correspondent for Logan and Bryon in New York. It was the most traumatic day, because I saw the whole financial world fall in. I can even today recall seeing men crying at the door, saying: “I’m destitute. I can’t go home and tell my wife that all the money is gone.”

By December the extent of the debacle was beginning to be clearer. The Vancouver Unemployed Workers’ Association had been formed, and on December 17 unemployed men raided the city relief office. There was much worse to come.

There was still some money in the civic kitty: on May 30 the city bought Little Mountain—now Queen Elizabeth Park—from the CPR for $115,270, and a couple of months later it was announced that Vancouver’s brand-new chief constable, W.J. Bingham—he had been a District Supervisor with London’s Metropolitan Police—would be given a three-year contract and an increase in pay to $6,000 a year. The Police Department had grown larger with the absorption of the police forces of Point Grey and South Vancouver. (One of Bingham’s chief concerns in the Vancouver of 1929 was Chinatown gambling. He said, however, that gambling was the “natural instinct” of the Chinese, and could never be repressed.) Over in the Fire Department, a familiar face was going: after an astonishing 42 years as chief of the department, John Carlisle retired. He was succeeded as chief by C.W. Thompson. Annie Jamieson was first elected to the Vancouver School Board this year. She would be elected again and again, and serve to 1946. An elementary school in Vancouver is named for her.

Two fires made more than average news in 1929: in July there was a serious fire in Ladner’s Chinatown. The settlement stretched along the river front and consisted of more than a dozen buildings. Half were destroyed in the blaze, which was reported in the Ladner Optimist newspaper: “Fanned by a tremendous wind, the fire burned like lightning through the dry wood and the damage was all done before firefighting equipment from Vancouver could reach the scene. Calls for help came soon after the blaze was discovered. Its origin is unknown.” And also in July the provincial exhibition buildings in New Westminster—the fair was due to open in September—burned down. They would use big tents instead.

The disappointment of the exhibition’s organizers at losing the buildings was ameliorated somewhat by a special invited visitor: Winston Churchill. On September 2 Winnie—described as “the former chancellor of the exchequer and holder of a dozen other cabinet positions in Great Britain”—arrived in New Westminster to open the exhibition. Some 40,000 people turned out to see him. The following day he travelled to Haney “for an inspection of British Columbia’s lumber industry.” His host was Nels Lougheed, provincial MLA and an executive of the Abernethy Lougheed Logging company, who gave him a demonstration of B.C. logging methods. He later gave a talk at the Vancouver Theatre on Granville Street. Next on his agenda: a trip up Grouse Mountain where he dined at the chalet. Churchill, who was on a tour of North America, was accompanied by his son Randolph, his brother Jack and Jack’s son John.

R.I.P.

A lot of notable people left us in 1929: the most well-known was architect Samuel Maclure. He died in Victoria, aged 69. Maclure was born April 11, 1860 in New Westminster. The son of a Royal Engineer, he was a brother of newspaper publisher Sara Anne McLagan. He is considered the most gifted of early B.C. architects. Maclure designed some 150 buildings either alone, with his firm, or in partnership with others. He designed many Shaughnessy Heights homes before the First World War. Janet Bingham and Leonard K. Eaton have each written a book about him.

Also well-known was Henry Tracy Ceperley, realtor. He died December 14 in Coronado Beach, Calif. at 79. He was born in Oreonto, NY, arrived in Vancouver around 1885. Ceperley Rounsefell & Co. (est. 1886), became one of B.C.’s largest real estate/insurance firms. In 1887 the company was renamed Ross and Ceperley Real Estate, Insurance and Financial Agents, with Ceperley in partnership with Arthur Wellington Ross. It was Ceperley who encouraged the CPR’s William Van Horne to promote the idea of Stanley Park in Ottawa. Ross and Ceperley controlled much of the land near the park, promoted it heavily after it was converted from a military reserve. Ceperley’s Deer Lake home is now the Burnaby Art Gallery.

Thomas Plimley, pioneer Vancouver auto dealer, died in Victoria, aged about 58. He’d started a bicycle business in Victoria in 1893, the year he arrived from England. He sold the first car in Victoria, a tiller-steered Oldsmobile, in 1901. Plimley Motors on Howe Street was one of B.C.’s largest dealerships. His grandson Basil (born in 1924 in Victoria) was one of the few third-generation executives of a B.C. business. The Plimley companies would close in 1991, after 98 years.

Peter Righter, the man at the throttle when the CPR’s first passenger train, #374, pulled into town in May of 1887, died at 77. For several years after that adventure, Righter served on the CPR line between Vancouver and Kamloops. In 1901, at age 49, an injury forced him to retire. In 1918, at age 66, he married. He was survived by his wife and a daughter.

Another man who died in February was Daniel Loftus Beckingsale, Vancouver’s first port doctor. He died in London England, at 82. Beckingsale was born November 18, 1846 on the Isle of Wight, came to Vancouver in June 1886, became the first port doctor and an early health officer. He was involved in the establishment of the Vancouver Reading Room, predecessor of the public library.

Vancouver’s first solicitor also died in February. Alfred St. George Hamersley, 80, died in Bournemouth, Eng. He practiced law in New Zealand, arrived in Vancouver in 1888. He became legal advisor to Vancouver City Corporation and the CPR. Hamersley was active in local business and athletics, once sold some Mt. Pleasant property—the southeast corner of Fraser Street and East 11th Avenue—to fellow Freemason, writer Rudyard Kipling. He returned to England in 1906.

Our first city treasurer, G.F. Baldwin, who had also been a school trustee, died in June. He’s visible in the famous City-Hall-in-a-tent photo, standing at the far right in the back row.

A New Brunswick-born Point Grey pioneer, Francis Bowser, died in Vancouver at age 71. He had served as a reeve of Point Grey when it was a separate municipality.

Finally, pioneer John Hess Elliott died in February, aged 65. He’s remarkable because when the First World War began he enlisted with the 242nd Battalion Canadian Expeditionary Force. At the astonishing age of 53 he chose to fight in the trenches of Europe alongside men less than half his age. He was severely wounded in battle and, shell-shocked, was unable to remember his own name. Evacuated to a hospital in England, Elliott remained unidentified until a fellow soldier recognized him and sent word home to his wife and family that he was alive. He was brought back to Vancouver on a stretcher, a decorated veteran.

1929 Fragments

On February 14, 1929 the St. Valentine’s Day massacre occurred in Chicago, when Al Capone’s gang killed seven members of “Bugs” Moran’s rival organization. See the 1967 chapter for a later and curious Vancouver connection.

On April 6 (coincidentally Vancouver’s own incorporation date) the city of Hope was incorporated.

June 1, 1929 was the first day of Uncle Ben’s Sun Ray Club. This was a “club” for kids whose parents read the Sun. It would eventually have thousands of members. The author was one in 1946.

On June 3rd the Peter Pan Restaurant opened at 1128 Granville. Said the Sun: “Thousands Inspect New Cafe.” A photo showed the staff lined up out front. This restaurant, soon to become a city landmark, was started by Peter Pantages of Polar Bear Swim fame.

John Napier Turner was born in Richmond, Surrey, England on June 7. He would become one of Canada’s shortest-serving prime ministers: 80 days in 1984.

On October 18 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that women were, after all, “persons.” A word of explanation: on April 24, 1928 the Supreme Court of Canada had ruled that women were not “persons.” The judges expanded on the judgement, ruling that “by the common law of England, women were under a legal incapacity to hold public office.” That paternalistic ruling was overturned, thanks in part to crusaders like Nellie McClung and Emily Murphy.

On December 18 Burnaby’s first street lighting was turned on, illuminating Hastings Street from Boundary to Gilmore.

A striking Japanese-Canadian War Memorial, designed by James Benzie, was installed at Stanley Park. It commemorates Japanese-Canadians who fought in World War I.

UBC’s Social Work program began, the third university social work program established in Canada after Toronto’s in 1914.

A kindergarten was renting Glen Brae, the Shaughnessy mansion, for $75 a month.

Artist Mary Riter Hamilton, aged about 56, arrived in Vancouver and would teach art here. She had been a battlefield artist during the First World War. A web site about her tells us: “In 1919 she was commissioned by H. F. Paton’s Gold Stripe, which was a tribute to those who were killed, maimed and wounded in the Great War, to produce paintings of the French battlefields for reproduction in the publication. She spent the years from 1919 until 1922 living in France alone in a tin hut amid Chinese workers hired to clear the Western Front of the debris of war. The conditions ran the gamut from uncomfortable to downright dangerous due to gangs of ‘criminals’ roaming the region.”

Frances Street in Vancouver’s East End was named this year after Sister Frances, a pioneer nurse at St. Luke’s Home and St. James Church on Cordova St.

Smoky Tom Island was purchased by George C. Reifel, and became Reifel Island.

Built from 1889 to 1895, Christ Church, the oldest surviving church in the City of Vancouver, became a cathedral this year. The cathedral stands at the northeast corner of Georgia and Burrard.

The Womens’ Auxiliary of the St. George Orthodox Hellenic Community was founded, and a branch of the Slovenian Society was opened in Vancouver. The Jewish Western Bulletin, a weekly newspaper on the Jewish community in Vancouver, began publication. So did the Swedish Press/Nya Svenska Pressen, a bilingual monthly newspaper.

Mary Louise Bollert, UBC’s dean of women, became president of the Confederation of University Women.

The Essondale Hospital fire department bought a new ladder and pumper truck in 1929. They would use it for 40 years!

United Church minister Andrew Roddan was appointed this year to Vancouver’s First United Church, “the church of the open door.” Roddan was an early advocate of low rent and housing projects in the East End, welfare services for the poor and a fresh air camp on Gambier Island. He would become locally prominent, partly because of his radio sermons.

Image, top: Library and City Hall, Vancouver – 1907 [CVA 135-05]