B. Marcus Priteca

The magic of what architect Benjamin Marcus Priteca created for theatre goers in the Orpheum is captured memorably in a Denny Boyd tribute to Ivan Ackery published in the Sun October 31, 1985, the day after Ackery died. In that column Boyd paid simultaneous tribute to the building over which Ivan had presided for so many years. Denny begins, in a comparison that would have mightily pleased the architect, by remembering his first view of India’s Taj Mahal: “I think the only other time I felt such a hammer blow of awe,” he writes, “was when I was seven and I approached the box office of the Orpheum Theatre for the first time with a King George V dime in my sweaty little fist.

“If you grew up in Vancouver through the mean, bleak ’30s, movies were the common escape and a dime was the key. If you lived in a 2 1/2-room flat, your family on relief, that dime took you up the lushly carpeted stairway of the massive Orpheum foyer into the world of imagination where animals spoke, Tarzan roared, children squealed with laughter and bad guys always got it before the closing credits.

“Most Saturdays, we Fairview kids went to the Stanley or the Roxy, nicknamed the Beanery, which stood precisely where I am writing this, at Sixth and Granville. On special Saturdays, a birthday, an extra dime gouged from the relief cheque to cover the streetcar costs, we went to the Orpheum to be dazzled.

“The rose-red carpeting led to the dramatic split stairway to the upper foyer, light cascading down from the chandeliers and the wall sconces. There were balustrades and ornate arches, pillars and colonnades, coffered and domed ceilings . . .

“I didn’t know Ivan Ackery then, only what he gave us. I sensed that someone was being terrifically kind to us on those Saturday mornings in the Depression, giving us two features, 30 minutes of cartoons, a Pete Smith specialty and the newsreel, all for a dime. We were made welcome . . .”

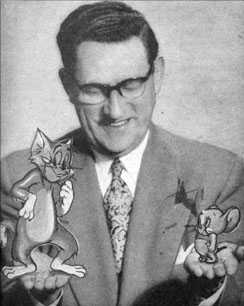

The man who designed the Orpheum to both dazzle and welcome, B. Marcus “Benny” Priteca, had been creating spectacular theatres like it since 1910. In his more than 50 years of activity, Priteca created a great many unique and—to say the least—colorful buildings.

Priteca was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on December 23, 1889. He took architectural training in Edinburgh—beginning as an apprentice at age 14 and earning the degree of “Master Architect” by age 20—and received a travelling scholarship to study architectural forms in the United States. He decided to stay there. By July, 1909 he had settled in Seattle, where he immediately went to work as a draftsman with architect E.W. Houghton. (Priteca’s drawings are superb.) Then, in 1911 the 21-year-old Priteca met Alexander Pantages, a Seattle resident and theatre owner. The young architect was delivering some illustrations he had made for a local architectural firm, and met Pantages there. Pantages was fuming over a theatre design he considered to be inadequate, and that led to a discussion of theatre design with Priteca.

Pantages was impressed by the superior quality of Priteca’s drawings, and the stocky little entrepreneur commissioned the young architect to design his next theatre, the San Francisco Pantages. The site presented challenges, but Priteca overcame them, the theatre opened in December, 1911 and Pantages was so pleased with the results he commissioned Priteca—now all of 22—to design all his theatres from that time on. That relationship continued for 18 years, and the two men prospered as the Pantages organization grew to become the largest privately owned vaudeville circuit in the world.

“When Mr. Pantages asked me to design him a theater,” Priteca once said, “he told me that any darn fool could design a million-dollar theater for a million dollars, but that it took a smart man to design a theater that looks like a million dollar theater and cost half that much.”

Pantages pretty much kept out of Priteca’s hair. “As a Greek, the only directions he gave me were to include pillars on either side of the proscenium stage . . . he bought expensive rugs and furnishings, elaborate crystal chandeliers, things that only the wealthy could have at home.”

The now-vanished Pantages Theatre on Hastings Street was Priteca’s first venture into Vancouver. That 1,800-seat theatre, which opened June 17, 1917, was later called the Majestic, then the Beacon and finally the Odeon Hastings. Architectural writer Miriam Sutermeister says it “was considered at the time to be the most richly embellished and efficient theater of the Pantages chain.” Its demolition in 1967 outraged Vancouverites, and has been called a rallying point for public support for the Orpheum’s preservation. (The architect of the earlier 1907 Pantages, also on Hastings Street, which is still there and being restored, was Edward Evans Blackmore.)

Seattle architect Richard F. McCann, who has made a study of Priteca’s work, says his great influences were Palladio and Vignola, innovative 16th century Italian Mannerist architects. The now vanished Seattle Pantages Theater (1915) was among his earliest works, and it combined a large auditorium with a substantial office building.

There were times when Priteca’s ideas went over the edge. His design for the Coliseum Theater at 5th and Pike in Seattle included fountains by the orchestra pit, and birdcages holding 30 canaries in the walls of the upper foyer. There was a children’s play room and nursery, with miniature furniture. At the time it opened January 8, 1916 the Coliseum was one of the few—some say the first—movie theatres in the world with an orchestra to accompany the silent films it showed. It also housed one of the world’s largest theatre organs. It was the only movie house in the world with an elevator. The decorative elements were by Tony Heinsbergen, who would bring the same wildy imaginative work to our Orpheum. (This spectacular building, by the way, still exists in Seattle, home today to a Banana Republic clothing store.)

Before he moved to Los Angeles in 1922, Priteca had designed theatres in Memphis, Kansas City, Fort Worth and Salt Lake City. He also found time to design many of Seattle’s downtown theatres—and Seattle schools, homes, commercial buildings, synagogues (one of his parents was Jewish, and he used to joke that he was one of the few Jews in North America entitled to wear a kilt), and the now-vanished Longacres Racetrack in Auburn, Washington, where for many years they ran a Priteca Handicap race. He had become one of the leading architects in the American northwest.

Oddly, he ventured into other design areas, too: he designed a body for the Locomobile car, and crafted a raked grill and windshield for the Paige, forerunner of the Graham-Paige automobile.

Pantages wasn’t his only source for theatre work. During his career Priteca worked for four different theatre chain clients, and designed more than 150—some say 200—theatres. (The Orpheum was designed, of course, for the Orpheum Circuit.) He referred to the elaborate style of that house and others as “conservative Spanish Renaissance.” But he borrowed from a dozen different places: the ornate ceiling of the Orpheum lobby, for example, is apparently based on one he saw and admired in India! The organ screens are Moorish North African; the ceiling arches in the auditorium are Gothic; the ceiling itself and its dome and the chandeliers are Baroque, and the wall coverings imitate those of the 19th century in France!

We know, thanks to the December 5, 1926 issue of the Journal of Commerce that Priteca was in Vancouver December 3, with his associate architect F.J. Peters and an Orpheum vice president, to look at bids made by local construction firms. We have also learned that because the bids were so much higher than had been anticipated for that aspect of the work that Priteca and his associates decided to scale back some of the more elaborate features he had planned. (The winning bid was put forth by Northern Construction Co. Ltd. and J.W. Stewart, the oldest construction firm in the city.)

Acoustics is a key factor in the design of theatres, and Priteca paid careful attention to his buildings’ sound qualities. Those graceful curving balconies, sloping floors and good sight lines are no accident. “Seeing is hearing,” he said. He was his own acoustical engineer. He doesn’t appear to have had any special training in the field, and it’s likely he relied on experience—his own, and others’. The late Dr. Vern Knudsen, a world-renowned specialist in acoustics (in the early days of radio and talking pictures Knudsen designed the acoustics of most of the original Hollywood sound stages) wrote for the layman a brief history of acoustics as applied to theatres, and specifically and approvingly cited Marcus Priteca’s work as a consultant in the conversion of the old Seattle Civic Center into the Seattle Opera House. “Sound is as much a part of man’s man-made environment as heat or light,” Knudsen wrote. “It can now be effectively managed, notably in rooms where music is heard, by applying the principles of acoustical physics . . .

“The application of acoustical knowledge to architecture,” Knudsen continued in this 1963 essay, “dates back barely 60 years. Until about 1900 the design of a successful music room was almost entirely a matter of luck. Today the design can be based on well-established principles of physics and engineering . . . The typical open-air amphitheater consists of steeply banked benches arranged in a semicircle in front of a platform. With the passage of time the platform evolved into a stage with massive rear and side walls of masonry (and sometimes a ceiling) that served the acoustical purpose of reflecting, directing and thereby reinforcing the sound intended for the audience . . .

“The principal defect of the Greek and Roman theaters,” Knudsen continued, “is that the semicircular tiers of seats act as reflectors that tend to focus sounds from the stage back to a point on or near the stage. Moreover, the echoes from concentric tiers are reinforced at certain frequencies and diminished at others. The reason is that the vertical risers, which form the backs of the benches, create an echelon of uniformly spaced reflecting surfaces.”

Priteca apparently solved this problem instinctively, and through long experience.

He would change styles again toward the end of his theatre-based career, adapting to changing tastes, and try his hand at Art Deco. Again, he was successful. His work on the Hollywood Pantages (opened June 4, 1930), his last theatre for Pantages, has been called “stunning.”

“The breathtaking decor, with its golden zigzag-style columns, statues, chandeliers, and intricate geometric motifs, has been called the most spectacular theater interior ever built in Los Angeles.” His decorator/muralist was, as usual, Tony Heinsbergen. Theatre historian Maggie Valentine has a delightful explanation for this switch to Art Deco design of theatres: She said the exotic decor of the early picture palaces reflected the silent and exotic nature of film in those times. Movies in the 1930s, however, “turned to romance and domesticity; Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire demanded an Art Deco showcase.” (Valentine also theorized on the move to the art deco style in the Depression: “Clearly tastes had changed. No longer did moviegoers expect a royal welcome from doormen, ushers and lounge attendants. The architectural treatments of movie palaces were now considered exuberant, if not downright wasteful.”)

Priteca worked into the 1960s, and his Temple de Hirsch Sinai Sanctuary (1960) in Seattle is counted as one of that city’s major buildings. At 73 he was taken on as a consultant in the conversion of Seattle’s Civic Auditorium into the Seattle Opera House for use in the 1962 World’s Fair in that city. He lived long enough, in fact, to outlast some of his theatres. Sadly, he witnessed during his lifetime the demolition of several of his creations, including the Seattle Pantages (which became the Palomar, and which was the site of Priteca’s fifth-floor office for all 50 years of its life) and the Seattle Orpheum, which had opened August 28, 1927, a little over two months before Vancouver’s. The Seattle Orpheum stood where the city’s Westin Hotel now stands.

B. Marcus Priteca died in Seattle October 1, 1971, too soon to see that one of his greatest creations, Vancouver’s Orpheum Theatre, would survive and thrive. He was 81.

“For some, life has been work,” he said near the end of his life. “For me, it has been a happy time. It has been nice.”