Glimpses

A Brief History of Greater Vancouver

Envision the span of human occupation in this area—say, 8,000 years—as the width of this computer screen. The events described in this short article could be fitted into a couple of centimetres on the right. Our “modern” story begins in the winter of 1824 with the Hudson’s Bay Company setting up a network of fur-trading posts on the Pacific slope.

A party of 40 men led by chief factor James McMillan reached what is now the Langley area December 16, 1824. They approached from the west, entering the Nicomekl River from its mouth on Boundary Bay, paddling through what is now Surrey, then portaging to the Salmon River. They entered the Fraser River about 50 kilometres from its mouth, then carried on north into the interior. But McMillan noted the location and chose a prominent tree, nicknamed the Hudson’s Bay Tree, to remind him of it. Two-and-a-half years later, aboard the Cadboro, he was back by the tree with 25 men and instructions to build a fort in the area. It would be called Fort Langley, after Thomas Langley, a Hudson Bay Company director. It was July 27, 1827.

That date is as good as any to mark the beginning of Greater Vancouver. (Fort construction began a few days later.)

Fur Trading Begins

The Kwantlen people left their winter villages at the mouth of the Brunette River to take up fur trading around the fort. In 1832 Fort Langley shipped out more than 2,000 beaver pelts. Then salted salmon became a major industry. By the late 1840s the fort was the largest fish exporter on the Pacific Coast, with Hawaii a major market. The original fort was abandoned in 1839 and a new one built 35 kilometres upstream, the present site. Next, farming became an important source of income. Thirty years after its establishment, Fort Langley was thriving.

Gold!

Everything changed in 1858 following announcement of the discovery of gold on the Fraser River. That news travelled quickly to California. Within weeks 25,000 American prospectors flooded in, prompting an alarmed James Douglas, the governor of the colony of Vancouver Island, to declare the mainland a British colony, too. The proclamation was made at Fort Langley November 19, 1858.

To ensure control of the new colony by Britain and discourage any thoughts of American expansion, a small detachment of Royal Engineers had been sent for to show the flag and build roads. The first 25 “sappers” arrived from England November 25, 1858 under the command of Col. Richard Moody. (The Engineers get their nickname from an old word, sap, a spade used in digging trenches.) Their settlement came to be called Sapperton. Today it’s a New Westminster neighborhood.

Colonel Moody

Richard Moody is the most important figure in Greater Vancouver’s early history. He selected the routes for our first roads, the sites for the first military reserves and the location of our first city. Moody was alarmed by Fort Langley’s strategically poor location on the south side of the river, with its “back” to the Americans. Calling on the advice of his officers he picked a more suitable site a little farther to the west and on the north bank. Called Queensborough at first, in tribute to Queen Victoria, it would become—at the suggestion of the Queen herself—New Westminster. (Because it was named by the Queen, New Westminster dubbed itself The Royal City.) It became the capital of the mainland colony, supplanting Fort Langley. Victoria was the capital of the colony of Vancouver Island. In 1866, when the two colonies were united, New Westminster became capital of both. But in 1868 Victoria regained the title.

North Road

In 1859 Moody had a trail built through the forest from New Westminster to ice-free Burrard Inlet; today, as North Road, it’s the boundary between Burnaby and Coquitlam. Not long after, he set aside a government reserve for a townsite that would come to be called Hastings. Superimposed on a city map today, Hastings Townsite would extend south all the way from Burrard Inlet to 29th Avenue between Nanaimo Street and Boundary Road. (A fascinating graphic account by Bruce Macdonald, in his book Vancouver: A Visual History, shows the process of the city’s physical changes over the years in maps and photographs. Macdonald’s book is an indispensable guide to the story of the city’s growth.)

Settlement Begins

People began to settle in what we know now as Burnaby and Delta. A dairy farm with 50 milk cows was established on the Pitt River. The False Creek Trail, closely following a very old native-built trail, was opened in 1860 between New Westminster and False Creek. Today’s Kingsway follows its route fairly closely. A school for the sappers’ children was built, and the first permanent church went up. (Oddly, there were no local sawmills yet, so St. John the Divine Anglican, consecrated May 1, 1859 at Derby, near Fort Langley, was built of imported California redwood!)

In 1861 the first newspaper (New Westminster’s British Columbian) appeared; in 1862 the first real hospital was built; a telegraph line went in in 1865 (its first message the assassination of U.S. president Abraham Lincoln); postal service began in 1867, and so did the first regular transportation service between New Westminster and Burrard Inlet . . . by stagecoach!

The “Three Greenhorns”

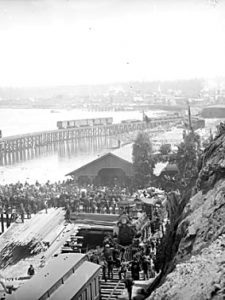

![[McCleery Farm] Land Pre-empted Sept. 26, 1862 by Fitzgerald McCleery](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/28a61432-a4e7-4abe-82c8-8ae2f8c2f0b1-CVA188-1-300x189.jpg)

(Image: Vancouver City Archives)

Brothers Fitzgerald and Samuel McCleery arrived September 26, 1862 and set up a farm in what would become the city of Vancouver. (And their farm would become a public golf course.) A month later a Yorkshire potter named John Morton saw a chunk of Burrard Inlet coal on display in a New Westminster shop window and wondered if near that coal there might be fine clay suitable for pottery. There was clay, but of a quality suitable only for bricks, and so Morton and two associates preempted 550 acres—at a price equivalent to $1.01 an acre—with a view to becoming brickmakers. (They spent, some thought, far too much money for the remote “Brickmaker’s Claim,” and one newspaper report derisively described them as “three greenhorn Englishmen.”) The “three greenhorns” built a cabin near the north foot of today’s Burrard Street and began to raise cows. The property they had selected, now the West End of Vancouver, made two of them wealthy, one of them (John Morton) very much so.

The native people, the original inhabitants of this bountiful corner of the world, found their occupation of the land ended, after thousands of years, with numbing speed.

Logging Begins

The trees that once thickly covered the Lower Mainland were magnificent: one mighty specimen was recorded at 300 feet, about the height of the Marine Building. With all that splendid wood standing around, it wasn’t long before intensive logging began. In 1862 two men, George Scrimgeour and T.W. Graham, preempted land for a sawmill on the north shore of Burrard Inlet and built Pioneer Mills. The mill sent a shipload of lumber to Australia in 1864, the earliest export of lumber from Burrard Inlet to a foreign port.

In June 1867 on the south shore of Burrard Inlet, Edward Stamp began—with British financing—Vancouver’s first major industry. Stamp’s mill (it was at the north foot of today’s Dunlevy Street) built a flume from Trout Lake to its sawmill to sustain its steam-driven machinery.

Gassy Jack Arrives

Confederation came in 1867, creating a new country away to the east called Canada, and naturally inspiring thoughts it might eventually stretch from sea to sea. That was the same year a talkative former riverboat captain, Yorkshire-born John Deighton, with a complexion of “muddy purple,” had a vision, although his wasn’t so lofty. Deighton paddled into Burrard Inlet on the last day of September with his native wife, her mother, her cousin, a yellow dog, two chairs and a barrel of whiskey and jovially greeted the men who worked at Stamp’s mill. The canny Deighton knew the nearest drink for these thirsty fellows was a five-kilometre row east up the inlet to the Engineers’ North Road, then a 15-kilometre walk along that rude trail through the forest, the elk and the bears to New Westminster. (Encounters with bears were not at all uncommon those days.) He announced to the mill workers they could have all they could drink if they helped him build a bar. The Globe Saloon was up within 24 hours. The locals had a nickname for Deighton, endlessly and garrulously confident of the area’s future. They called him “Gassy Jack.” That led, the story goes, to the area around his saloon—a gathering spot for mill-workers and visiting sailors—being nicknamed, in turn, “Gastown.” There are other theories for the origin of the name, one associated with a nearby pocket of natural gas.

The irascible mill manager Edward Stamp had a falling out with his English investors and left. The operation, quickly under new ownership, became the Hastings Mill. This was, as historian W. Kaye Lamb has written, “the nucleus around which the city of Vancouver grew up in the 1880s.”

Electricity!

Our wood would become famous around the world. There are immensely long, knot-free beams in the Imperial Palace in Beijing, China, cut from Burrard Inlet lumber by famed Jerry Rogers and his men. Forestry brought quick prosperity to the Lower Mainland. By 1875 a village that had sprung up around the north shore mill-now owned by an American named Sewell Moody, no relation to the colonel, and called Moodyville in his honor—could boast the inlet’s first library, the first school and, in 1882, the first electric lights on the Pacific coast north of San Francisco. The mayor and city council of Victoria came over to watch them being turned on.

For all our progress in creating new places and in settlement and construction and industry, we were still backward when it came to human rights: on April 22, 1875 Queen Victoria gave Royal Assent to an act passed in the B.C. legislature denying the vote to Chinese and native people, a decision in force for more than 70 inglorious years.

Langley Born

Meanwhile, the boundaries of Greater Vancouver commenced to be drawn. The first entry, in 1873, a big one, was called the District of Langley, named for a Hudson’s Bay Company director. In 1874 Maple Ridge was created, the outcome of a meeting held in a dairy farm—also called Maple Ridge, for a long, beautiful ridge of the trees, more than three kilometres of them along the Fraser River. Huge chunks of the map were filled in in 1879 with the creation, all on November l0th, of Surrey, Delta and Richmond. Their populations numbered in the mere hundreds at the time.

Scattered settlements had been made in other places all over the Lower Mainland. Brothers William and Thomas Ladner had settled in the Fraser River lowland in 1868. Their farms grew into the pioneer settlement of Ladner’s Landing. The rumpled little settlement that had coalesced around Gassy Jack’s saloon and the Hastings Mill got the formal name Granville Townsite in 1870. The first recorded white settler on Bowen Island was Charlie Daggett, who logged there in 1872. In May of 1878 Manoah Steves and his family settled on the southwestern tip of Lulu Island, an area later called Steveston.

BC Joins Confederation

In 1871 British Columbia, assured by Canada that its entry would bring it the railway, joined Confederation. Now British Columbians were also Canadians. If they had known that the railway wouldn’t reach them for another 15 years, they might not have been so willing to join! Port Moody, at the eastern end of Burrard Inlet, was in a fever of speculation as the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) line grew nearer. The little settlement had been announced as the railway’s Pacific terminus. (It’s a slightly bizarre fact of local history that the first CPR locomotive arrived here by sea!) But Port Moody’s optimism was misplaced. A CPR official had come out for a closer look at the location and gone back with a melancholy secret: the eastern end of Burrard Inlet was too shallow for the ocean-going ships that were part of the railway’s global shipping plans. In August of 1884 the dynamic and forceful William Van Horne, general manager of the railway, visited Granville. A little more than a month later, he asked CPR directors to choose it as the line’s western terminus, instead of Port Moody. They agreed. When the announcement was eventually made, the people of Port Moody erupted in rage at what they considered an act of betrayal and began a series of law suits. None was successful.

CPR Dominant

There was an even weightier factor in the decision to move a little farther along the inlet. “The CPR,” as David Mitchell writes in The Greater Vancouver Book,”was anxious to develop a sizable new townsite . . . since the official Pacific terminus was to be at Port Moody, the railway’s property entitlements from the government of Canada ended there. As a result the CPR secretly entered into negotiations with the provincial government of British Columbia for Crown land on Burrard peninsula. An initial request for 11,000 acres was rejected but a counter-offer of 6,000 acres was agreed upon, subject to an extension of the rail line from Port Moody to a new CPR terminus ‘in the immediate vicinity of Coal Harbour and English Bay . . .’ The CPR would become the dominant private landowner in the new townsite.”

William Van Horne is also responsible for the city’s name. The legend, likely true, is that an excited Van Horne was rowed around what became Stanley Park by the CPR’s local land commissioner Lauchlan Hamilton—another version has realtor Alexander Wellington Ross at the oars—and exclaimed that the city was destined to be a great one and must have a name commensurate with its greatness. Nobody would know where “Granville” was, Van Horne told whoever was rowing, but everyone knew of Captain Vancouver’s Pacific explorations. The town’s new name was in use early: the first issue of the city’s first newspaper, the Vancouver Weekly Herald and North Pacific News, preceded incorporation by three months.

In 1885 Hamilton began to lay out the Vancouver townsite. A plaque at the northwest corner of Hamilton and Hastings streets marks his starting place.

Vancouver Incorporated

When the CPR announced Vancouver would be the railway’s terminus, the town’s population was about 400. (Four years after the railway arrived, it was 13,000.) Incorporation came April 6, 1886 at a modest ceremony in Jonathan Miller’s house. A civic election followed quickly. A month later the first piece of business at the first meeting of Vancouver’s first city council, presided over by its first mayor, Malcolm Maclean, was the drafting of a petition to lease from the federal government a 1,000-acre military reserve to be used by the city as a park, That became Stanley Park.

The tiny city, a ramshackle tumble of stumps, brush and crude wooden buildings was little more than two months old on June 13, 1886 when a swift and furious fire—started when a sudden freak squall blew in sparks from clearing fires to the west—destroyed it in a time recalled as anywhere from 20 to 45 minutes. The Great Fire left a pitiful scattering of buildings.

Rebuilding began within hours, this time with brick, and while the fire’s embers were still smoking.

The First Train

Less than a month later (July 4, 1886) the first scheduled CPR transcontinental passenger train reached a still cranky Port Moody and, also in July, the first inward cargo to the port of Vancouver—tea from China—arrived. Then Vancouver’s first bank, the Bank of British Columbia (no connection with today’s), opened. The first CPR passenger train to arrive in Vancouver, famous little #374, chugged in in May of 1887, adorned with a large photograph of Queen Victoria. The first passenger to step down onto the platform was a 22-year-old Welshman named Jonathan Rogers who would become a prominent Vancouver developer and philanthropist. A band began to play a triumphant ditty called See, the Conquering Hero Comes. Rogers later laughingly admitted he thought they were playing it for him. The first train was followed a month later by the arrival from Japan of the CPR-chartered S.S. Abyssinia with a cargo of tea, silk and mail bound for London. The Abyssinia’s arrival marked the beginning of the trans-Pacific, trans-Atlantic trade using the new railway. It left no doubt the little city was going to thrive.

But not without tensions. The same year, 1887, a white mob attacked and wrecked a Chinese camp in False Creek. (A contractor had hired Chinese laborers for work at 75 cents a day when white laborers were asking $2.) Special constables had to be brought in from Victoria and the city’s charter was briefly suspended.

Intolerance has been a constant in our history from the beginning, sometimes with official sanction: in July of 1885 an act to restrict and regulate Chinese immigration into Canada received royal assent. It was the first of many enactments to discriminate against the area’s large Chinese population, another of which was to impose a head tax of $50. The result (intended) was that Chinese men could not afford to bring their families over to join them. Later that same year a resolution of Richmond Council provided that white labor only would be employed on municipal works contracts. Similar resolutions were passed in many Greater Vancouver municipalities in the late 19th century. Electricity came to Vancouver in 1887.

North Vancouver, Coquitlam and Burnaby

With the population on the north shore increasing, a group of locals applied to the provincial government to incorporate, and on August 10, 1891 the District of North Vancouver was born. Moodyville was invited to be in the new municipality but refused. (Years later it would join North Vancouver City.) The district was huge: it stretched along the north shore all the way from Horseshoe Bay to Deep Cove. The population was sparse, a few hundred.

Later in 1891 Coquitlam was created. Two men named Ross and McLaren had built Fraser Mills, the largest mill in B.C. at the time, capable of producing 200,000 board feet of lumber in a 10-hour shift. Coquitlam had grown up around it.

Settlers had been establishing homes in the area north of New Westminster, writes historian Pixie McGeachie, and they “decided their tax money should be used for their roads and services instead of going to Victoria.” Burnaby was born on September 22, 1892. That was the same year the municipality of South Vancouver was created. Greater Vancouver’s population now was more than 20,000.

The first of the area’s several “secessions” was next. Property owners in North Vancouver’s lower Lonsdale area felt they had little in common with the loggers of Capilano and Lynn Valley, and decided to incorporate separately as a city. When North Vancouver City was carved out of the surrounding district in 1907 it had almost 2,000 residents and 53 businesses, a bank, two hotels and a school. Electric service and the telephone had arrived the year before.

West Vancouver

In 1912 the western part of the district would break away to form another municipality, West Vancouver, with a population of 700. Some 28 kilometres of ruggedly handsome shoreline had been attracting people from the southern shores of the inlet, vacationers who pitched tents here during the summer months as relief from the “busy haunts of man.” A regular ferry service across the inlet had been started in 1909 by an entrepreneur named John Lawson, called by some “the father of West Vancouver.” That triggered a real estate boom.

The Pace Quickens

Meantime Vancouver had been having an unbroken boom of its own for 20 years, with the railway bringing in new arrivals every day. The city’s population leaped from 13,709 to 29,000 in the 10 years between 1891 and 1901 … and then it began to explode. The CPR’s first Hotel Vancouver had opened in 1888, the year after the railway arrived. The company—which was reaping a bonanza from sales of its property—built the lavish Opera House where Sarah Bernhardt would perform in 1891. Stanley Park was officially opened, the B.C. Sugar Refinery was gaining new markets, the first Granville Street bridge leaped bravely across False Creek and The Vancouver Board of Trade launched itself with a banquet in which every attendee got a full dinner and a bottle of fine champagne, Tab: $12.50. The Vancouver Club and the Terminal City Club, private clubs for monied businessmen, began. Electric streetcars began to clang along city streets, leading quickly to the famed Interurban lines to Burnaby, Steveston, New Westminster and the Fraser Valley. The first of the CPR’s Empress line of ocean liners pulled into port. Canneries at Steveston were shipping salmon everywhere, setting a record in 1901 with 16 million pounds. With all this growth and new sophistication there were occasional reminders it could still be a raw, largely untamed place: there were more anti-Asiatic riots in 1907, a Vancouver by-law restricted the number of cows that could be kept within city limits, and Burnaby’s first law enforcer included among his regular duties the reporting of swine running loose.

Culture was not confined to Sarah Bernhardt. The movies got here in 1897, and Pauline Johnson read her poetry here to an attentive audience that included an ex-prime minister, Sir Charles Tupper. We got pay telephones in 1898.

Growth became almost frenzied. Boosterism bordering on arrogance is reflected in the newspapers of the time. A banner across Granville Street proclaimed, in what we would now view as a politically incorrect rhyme, “In 1910 Vancouver then will have 100,000 men.” It did, and more.

Newspapers Thrive

Newspaper rivalry was keen here, with as many as four dailies fighting for circulation. Louis D. Taylor’s World was flourishing, to put it mildly. In 1912 he built a tower to house it, at the time the tallest building in the British Empire. Taylor—who would set a record (eight times) for being elected mayor that still stands—boasted that the World carried more display advertising than any other newspaper in North America. Most of it was for real estate. The Province, which had started in Vancouver in 1898, was doing pretty well for itself, too. One edition of the era had no fewer than 60 full pages of realtors’ advertisements. Among the more aggressive land peddlers was the Prussian Gustav Konstantin von Alvensleben, one of the great characters in Vancouver history.

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 would prove beneficial to Vancouver, considerably shortening ocean journeys between British Columbia and Europe and spurring the port’s growth in grain exports. Today we ship more grain than any other Canadian port.

UBC

Greater Vancouver’s educational life took a leap forward in 1915 with the establishment of the University of British Columbia—even though UBC would take many years to finally settle in at Point Grey, spurred by a “Great Trek” in 1922 of more than a thousand impatient students, angry at being cooped up in the “Fairview huts.”

The year 1915 also saw the opening of a new CPR station at the north foot of Granville Street and the creation of an industrial enclave from soil dredged out of False Creek, piled onto a mudflat, and proudly named Granville Island. The effervescence of the era is captured in the premiere that same year of a frothy little musical show set in Vancouver and called Fifty Years Forward. One of its predictions for Vancouver in 1965 was a lady mayor. After more than 90 civic elections, it hasn’t happened yet.

Prosperity and growth was not confined, of course, to the biggest guy on the Greater Vancouver block. On the north shore of Burrard Inlet the Pacific Great Eastern Railway (PGE) had started regular passenger service in 1914 between North Vancouver and Whytecliff near Horseshoe Bay. It was a small beginning in its torturously slow progress into the province’s interior. Wallace Shipyards in North Vancouver was building boats and saw a leap in orders during World War I. Marine Drive on the North Shore opened to traffic in 1915, the same year White Rock’s famous pier was built. (White Rock, by the way, was flourishing as a lumber centre.) Imperial Oil moved its refinery to what became the Ioco area in 1914, and started a townsite there. Further east, Robert Dollar began his mill at Roche Point on Indian Arm. In Hammond a mill built in 1916 is still there, Maple Ridge’s largest employer. Just to the west of Maple Ridge, a new addition to the Greater Vancouver map was created in 1914 with Pitt Meadows. (The map would now stay unaltered for decades until Langley City’s 1955 breakaway from the township.)

Bowen Island

Bowen Island and Horseshoe Bay had become flourishing summertime haunts. In 1921 a dance hall, the largest in B.C., was built on Bowen, allowing 800 people to shimmy at once. Radio broadcasting began, adding to the fun. The Pacific Highway opened down to the border crossing at Douglas, which made it easier to drive to Bellingham and Seattle … and easier for visiting Americans to drive up. By the late 1920s more than 300,000 of them were doing just that every year.

Vancouver Gets a Lot Bigger

By 1928 the population of the Lower Mainland outside Vancouver was over 150,000. More than 80,000, however, were residents of the municipalities of South Vancouver and Point Grey, both of which decided in 1928 to amalgamate with Vancouver. When newly elected mayor W. H. Malkin walked into his office January 2, 1929 he was the chief executive of a city that had, overnight, grown in population by more than 50 per cent to become the third largest in Canada.

Malkin, whose wholesale grocery firm was a city institution for decades, is one of a handful of pre-World War II Vancouver mayors whose names many still remember. Men like McBeath, Findlay, Buscombe and Collins have faded from memory, while Malkin, Taylor, Oppenheimer and Tisdall are still recalled. Preeminent among all the mayors, however, was the remarkable, the ebullient, the unstoppable Gerald Grattan McGeer. Gerry McGeer blew into office in 1935, burying L.D. Taylor by more than 20,000 votes. “McGeer,” writes Donna Jean MacKinnon in The Greater Vancouver Book, “was voted into office on a mandate to fight crime, and to do away with slot machines, gambling, book-making, white slavery and corruption in the police force. True to his promise, he confiscated 1,000 slot machines in his first week.” McGeer used all that zeal and vigor and not a little cunning to force through the location in 1936 of a new city hall at 12th and Cambie in the Mount Pleasant area. At the time many thought that remote location—so far from the city’s business district—was ridiculous. His 1935 reading of the Riot Act at Victory Square, to dispel a mob of angry unemployed workers, splits local opinion along partisan lines to this day.

The Depression

The Great Depression hit the area hard. There were breadlines and demonstrations at city halls. A fellow named Woodsworth came to town to talk about a new political party called the Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). Greater Vancouver residents formed the Common Good Cooperative Society to engage in a “war against poverty.” It ran a store, grew food on vacant land and helped give birth to the credit union movement in B.C. In 1935 a thousand unemployed men boarded freight cars in Vancouver to begin an “On to Ottawa” trek. Burnaby, West Vancouver and both North Vancouvers went into receivership and were run by public trustees for a time.

Not all the news was gloomy during the Depression years: in May 1930 Dominion Bridge opened a plant in Burnaby to produce steel for construction, In 1931 the Vancouver Art Gallery opened. So did St. George’s private school for boys. At Vancouver Golf Club during the lean times, dues were reduced from $6 a month to $1.

In 1935 the ward system ended in Vancouver. Despite several indications since that a slight majority of the city’s residents favor going back to the system—which would guarantee representation from all city areas—craftily worded questions on the subject have succeeded in avoiding a true test at the polls. What Paul Tennant wrote for The Vancouver Book back in 1976 could go unchanged today: ” . . . politically active persons are not a cross section of the population . . . persons and groups of little education and low income still tend to avoid civic politics. Those who are active in Vancouver politics are mostly from the professional-managerial category and more often than not live west of Main Street . . .” Vancouver is the only large Canadian city without a ward system. It might prove in practice no better than the at-large system, but a chance to test their relative merits hasn’t yet been taken. That may change.

British Properties

In October 1931 West Vancouver agreed to sell 4,000 acres of its mountainsides to a syndicate called British Pacific Properties. That turned out to be a landmark decision. To lure property buyers to its extensive new holdings, the syndicate (controlled by the Guinness Brewing Company) offered to build a bridge across the First Narrows. The fact that the road leading to the bridge would cut through the middle of Stanley Park made a lot of locals furious, but the work it would provide — not to mention the economic benefits to follow—made the decision inevitable: Lions Gate Bridge (costing $6 million) opened to traffic in November 1938. It brought an immediate boost to the fortunes of the North Shore.

And it foretold one of the great themes of the area’s history: the growth of suburban Vancouver. The 1941 census showed the metropolitan population had increased to more than 400,000, with about 70 per cent of us in Vancouver itself. Ten years later the relevant figures would be 590,000 and 58 per cent.

World War Two

World War Two yanked Vancouver out of the Great Depression, as it would do elsewhere. Local shipyards began to build corvettes and minesweepers. The Boeing Aircraft factory in Richmond took on 5,000 people to produce parts for B-29s. The newly incorporated Wartime Housing Limited began building rental units for war industry workers. WHL built nearly 800 homes on the North Shore.

In early 1942 in the wake of the December 7, 1941 Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, local Japanese-Canadians were herded into holding areas at Hastings Park and then removed to government camps in the Interior. Their fishboats, homes and other property were “taken into custody.” The owners received little or no compensation. A light in a Stanley park monument built to honor Japanese-Canadian soldiers who had fought bravely and with high casualties in World War I was extinguished. (Masumi Mitsui, the last surviving Japanese-Canadian World War I veteran, would relight the flame in 1985.)

World War Two changed the lives of women, as it would do elsewhere. Single women from the Prairies came to work in Fraser River canneries during the war. Many of them married local fishermen and stayed on. Out of a work force of 13,000, a thousand women worked at busy Burrard Dry Dock where, at the war’s height, 34 “Victory” ships were built in 26 months. (When victory was announced in 1945 some women at Burrard found themselves in tears knowing their jobs had ended and that, despite a fight by their union to keep them on, the returning men would necessarily put them out of work.)

Radio and Television

A remarkable success story began during the war when an imaginative fellow named Bill Rea started radio station CKNW. Rea realized local people wanted war news, so from the day the station signed on (August 15, 1944) he started hourly newscasts and stayed on the air 24 hours a day. No one else was doing that, and it immediately made this little New Westminster-based station noted and, eventually, dominant in local radio. It helped NW to have a late-night disc jockey named Jack Cullen, a broadcasting phenomenon who was a major name in local radio for more than 50 years.

The 1940s also brought us Canada’s first drive-in theatre, two-way escalators in the Hudson’s Bay store and, in 1948, on a tiny smattering of grey flickering screens the first television signal: a college football game played in Seattle. Chinese and East Indians were given the provincial vote in 1947, with Japanese and native Indians winning it in 1949.

The 1950s

What did the 1950s bring us: further expansion at Vancouver airport with CP Air beefing up its flights across the Pacific, inaugurating flights to Amsterdam and introducing jet aircraft; the Lougheed Highway; the Upper Levels Highway; completion of the PGE Railway (now BC Rail) from Squamish to Horseshoe Bay; a provincially owned Lions Gate Bridge; the Oak Street Bridge; death to the streetcar and the Interurban; a new phenomenon for Canada, a “shopping centre,” at Park Royal; another, called an “industrial park,” on Annacis Island; still another; the world’s first “container ship,” an initiative of the White Pass & Yukon Railway; atomic bomb shelters; an oil pipeline from Edmonton; Cleveland Dam; the Deas Island (George Massey) Tunnel; an end to ferry service between Vancouver and North Vancouver, balanced by an announcement of a new ferry service, the SkyTrain, between those same two places. The B.C. Lions football club was born.

We got a big new central branch for the Vancouver Public Library at Robson and Burrard, where it would stay long after it had become too small for what it held; our own television station in late 1953 when CBUT, the CBC’s local channel, signed on. CBUT brought us world-wide publicity the following year when it broadcast the “Miracle Mile” at the British Empire Games at Empire Stadium, the first time two runners (Roger Bannister and John Landy) both ran the mile in under 4 minutes, and the first sports event broadcast live to all of North America. Some saw a weakening in our moral fibre in the decade with the approval of, first, a six-day shopping week; second, the opening of Vancouver’s first cocktail bar in the Sylvia Hotel; and, third, rock ‘n roll when an incredibly loud little band called Bill Haley and the Comets starred in a 1956 show hosted by an incredibly fast-talking young disc jockey named Red Robinson. There was tragedy in 1958 with the collapse during construction of a new Second Narrows Bridge. Nineteen men died.

Next, for the first time in just over 40 years, the Greater Vancouver map changed, with the creation in 1955 of Langley City as a separate municipality. Two years later White Rock broke away from Surrey to become a haven for sun-seekers and retirees.

The 1960s

Suburban growth continued. By 1961 the metropolitan Vancouver population had climbed to more than 800,000, double the figure of 20 years earlier, pushing Vancouver’s share of the population down to 46 per cent.

In the 1960s we gained Nitobe Memorial Gardens, the Second Narrows Bridge, the 401 freeway (now called Highway 1), Whistler as a ski resort, direct distance dialing and provincial ownership of the British Columbia Electric Co. We greeted the Queen Elizabeth Playhouse, the first Vancouver Sea Festival, the Grey Cup, bathtub races, French-language radio and the Beatles. BCIT opened, as did the Grouse Mountain Skyride, Whistler’s first ski-lifts, the Port Mann bridge and, in Richmond, the Iona Island Sewage Treatment Plant.

We lost the Lyric Theatre and Bowen Island’s Union Steamship Hotel to obsolescence and the first Grouse Mountain chalet to fire.

Midway through the 1960s Simon Fraser University opened in Burnaby. The decade was marked here as elsewhere by protests against the war in Vietnam, peace rallies and marches. A new kind of people called “hippies” appeared and made Vancouver’s West 4th Avenue their neighborhood. Protest flared up in 1967 when Strathcona residents—many of them Chinese who had lived there for decades—squelched a freeway through their neighborhood, a major event in the city’s history. The world’s preeminent environmental activist group, Greenpeace, was born in a Dunbar neighborhood living room. The era of protest would continue into the 1970s with hippies clashing with Mayor “Tom Terrific” Campbell, and thousands of high school students demonstrating against U.S. atomic-bomb tests on Alaska’s Amchitka Island.

Grace MacInnis of Vancouver became B.C.’s first female member of parliament, and Surrey elected as mayor one Bill Vander Zalm. The Canadian Lacrosse Hall of Fame opened, and so did the Bank of British Columbia and, in Richmond, so did the first McDonald’s restaurant in Canada (with hamburgers at 18 cents). Vancouver’s Community Arts Council sponsored a walking tour of Gastown to stimulate interest in preserving the historic area. The Centennial Museum and the H.R. MacMillan Planetarium opened at Vanier Park. Swangard Stadium was built in Burnaby. The Canucks would play their first game in 1970.

The Greater Vancouver Regional District was incorporated in 1967, bringing a new level and a new kind of government to the Lower Mainland. In 1971 the census showed the metropolitan population had topped the million mark. (One remarkable finding of that census was that Delta’s population had tripled in 10 years.) A tiny part of that million was little Lions Bay, incorporated in 1971 with a population just over 1,000. And 1971 was the year even tinier Fraser Mills, population under 200, was absorbed into Coquitlam.

The 1970s

Canada’s economic links to the Pacific Rim were boosted with the opening of a coal port at Delta’s Roberts Bank in the 1970s. The city’s infrastructure expanded with a new Georgia/Dunsmuir Viaduct, the Knight Street Bridge, a big container facility for the port, an archives building named for the late city archivist, Major J.S. Matthews, and the Stanley Park seawall. A 1974 experiment, the Granville Mall, is still being tinkered with. Continuing growth at Vancouver International Airport made a new link necessary: Arthur Laing Bridge opened. Post-secondary education came to the North Shore with the opening of Capilano College. Grand new traditions began with the inauguration of the Royal Hudson steam train run from North Vancouver to Squamish, the launch of the world’s first children’s festival and the opening of the stunning Museum of Anthropology at UBC, architect: Arthur Erickson’s greatest Vancouver creation. Erickson and his associates would change the face of downtown in 1979 with the new courthouse and Robson Square complex.

Change was frequent in this decade: a small church in the city’s East End turned into the Vancouver East Cultural Centre; the old (1927) Orpheum Theatre was bought by the city and became a home for the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. Shaughnessy Golf Course changed to Van Dusen Botanical Gardens. The venerable old Birks Building came down, despite protests, to be replaced by an office/retail complex called Vancouver Centre. The Gastown Steam Clock, the world’s first, began to pipe up, and is today likely the single most-photographed object in Greater Vancouver, even though—horrors!—it turns out it was never steam-powered. An era could honestly be said to have ended when the last scheduled passenger train pulled out of the old CPR station on Cordova Street on October 27, 1979, just over 92 years since the first had pulled into town. (Today, the handsome old building is home to offices, shops, snack bars and the SeaBus terminal.) A rare phenomenon occurred as the 1970s ended: an initiative by the federal government turned into a smashing success with Granville Island’s conversion to a site for a big public market, and a range of handsome shops, restaurants and offices.

Whistler became a Resort Municipality in 1975, the only one with that designation in B.C., and West Vancouver gained the dramatic Cypress Provincial Park. A Coquitlam NDP MLA named Dave Barrett was elected premier, and Canada’s first Native Indian citizenship judge was appointed. A 1976 United Nations conference called Habitat focused on the supply of fresh water to millions in the undeveloped world. In sports, the Vancouver Whitecaps won the NASL Soccer Bowl. A new member of the Greater Vancouver Regional District popped up in 1979 as the Village of Belcarra, where Burrard Inlet meets Indian Arm.

The 1980s

By 1981 two-thirds of Greater Vancouver’s population lived outside the central city. The 1981 census was sobering for Vancouver: it showed a drop in absolute numbers, with 12,000 fewer people in the city since the ’71 census. Most of the suburbs were leaping ahead: Langley Township had more than doubled in population in a decade, Surrey grew by more than 50 per cent, Richmond by more than 55. Delta was now five times bigger than it had been 20 years earlier. Only New Westminster joined Vancouver: its population dropped 10 per cent during the 1970s.

To open the 1980s, Terry Fox captured the hearts of the entire nation with his courageous attempt to run across Canada. Annual Terry Fox runs raise millions of dollars for the fight against cancer.

Under the dome in 1983 Queen Elizabeth invited the world to Expo 86. Enthusiasm for the world exposition was tempered by nagging unemployment, with, among other gloomy news, word that none of five shipyards on the North Shore had any new shipbuilding contracts pending. The Social Credit government’s restraint policy inspired a “Solidarity” rally at Empire Stadium, at which more than 40,000 public and private sector workers aired their protests.

The B.C. Penitentiary in New Westminster closed. A new courthouse went up in New Westminster, and an old hotel, the Devonshire, was imploded in Vancouver. Also blown up, but in the opposite direction, was the fabric dome of B.C. Place Stadium. Premier Bill Bennett opened it in June 1983. Kwantlen College opened in Richmond and Douglas College moved to downtown New Westminster. The Vancouver Art Gallery relocated to a refurbished 1916 courthouse.

A 1981 peace march against nuclear arms in Vancouver became an annual event, the largest of its kind in North America, with up to 100,000 participants, A ‘temporary” facility called the Vancouver Food Bank opened. By 1989, it had grown to six depots distributing to 15,000 people every month.

The City of Vancouver celebrated its 100th birthday in 1986, and opened its doors on May 2 to more than 21 million Expo visitors. The success of the Granville Island Public Market inspired similar ventures at New Westminster Quay, at Lonsdale Quay in North Vancouver and in Richmond’s Bridge Point Harbour Market. Vancouver’s advanced light rapid transit system, the SkyTrain, opened. Two new bridges sprang across the Fraser: SkyBridge (to carry SkyTrain into Surrey) and the Alex Fraser Bridge. Burnaby’s vast Metrotown complex opened. So did the stunningly beautiful Sun Yat-Sen Gardens in Chinatown and the Vancouver Trade and Convention Centre in the former Expo 86 Canada Pavilion site. A “Shame the Johns” operation began in Vancouver in an attempt to drive prostitutes’ clients from the West End. It simply drove them elsewhere.

After 123 years The Columbian, B.C.’s oldest newspaper, stopped. Pope John Paul II made the first Papal visit ever to Vancouver and the Lower Mainland, which didn’t prevent Woodward’s from becoming the first major Vancouver department store to open on Sundays.

New stars were created in the 1980s: Rick Hansen began his around-the-world Man-in-Motion Tour by wheelchair to raise millions for research into spinal cord injury. Cross-country runner Steve Fonyo duplicated Terry Fox’s fund raising ability at first, then ran into severe personal roadblocks. North Vancouver singer Bryan Adams, who once washed dishes at the Tomahawk Grill, became—and remains—a global superstar. In other cultural news, a dwarf-tossing contest at the Flamingo Hotel in Surrey’s Whalley neighborhood made headlines. The B.C. Lions won the Grey Cup again.

Surrey’s Bill Vander Zalm won election as premier. Surrey made more headlines in 1988 when B.C. Tel reported that 40 per cent of all new homes built in B.C. that year were located there. Other big economic news as the decade wound down: it was announced that the Port of Vancouver was now handling more imports/exports than any other port in North America; and that 30 per cent of those exports were going to Japan.

The vacant Expo site was sold to Li Ka-shing of Hong Kong in one of the biggest real estate deals in Canadian history, for a price many believe was a fantastic bargain. Li’s Concord Pacific development is transforming the site into the largest urban project in North America.

More 1989 openings: Simon Fraser University’s downtown campus; Science World; Highway 91; and Cannell Studios in North Vancouver. Local movie audiences delighted in seeing familiar landmarks in big-budget Hollywood movies filmed here. Vancouver is now North America’s third largest film production centre, after Los Angeles and New York. We got a big new urban park, too, with the 750-hectare Pacific Spirit Park, created from part of the UBC Endowment Lands.

The 1987 addition of the brand-new Village of Anmore and the 1989 inclusions of Langley and Maple Ridge completed the map of the Greater Vancouver Regional District.

The 1990s

The 1990s began with a roar as the first “Indy” race took place in downtown Vancouver, the start of what has become an annual event. What was gained in the city was lost in Coquitlam when Westwood Motorsport Park closed after 30 years. SkyTrain service was extended to Scott Road station in Surrey.

Small blue plastic bins began showing up at residential curbsides as recycling caught on.

Big news in the 1990s was Canada’s first female premier (Rita Johnson, MLA for Newton in Surrey, who was chosen after Bill Vander Zalm resigned.) The Bob Prittie Metrotown Branch of the Burnaby Public Library opened. There were conspicuous deletions in the decade: Oakalla Prison Farm; Versatile Pacific Shipyards (due to celebrate its 100th anniversary in 1994) and Woodward’s, a retail institution.

The Canucks lost the Stanley Cup in the final game of the 1994 season, a nail-biting blazer of a series that led to frustrated fans rioting downtown. The B.C. Lions gained their third Grey Cup in ’94, defeating Baltimore. The Lions were in trouble in late 1996 with the departure of chief coach Joe Paopao and lukewarm response to a season tickets drive.

The world’s largest LSD (and other ‘designer drugs’) factory was raided in Port Coquitlam, and its head, a long-sought U.S. fugitive, was nabbed by the RCMP.

One thing that stopped happening in the 1990s was the trend to Vancouver having an increasingly smaller share of the metropolitan population: 1995 estimates show the central city’s population had increased by more than 107,000 since 1981—a 26 per cent jump! “Our city,” says Larry Beasley, Vancouver’s director of central area planning, “is emerging as an unbelievably unique place. We have tens of thousands of citizens who have elected to move back into the city.” 1996 census figures showed a net increase in the downtown residential population for the first time in decades.

Coda

What you’ve just read is an article I wrote for 1997’s The Greater Vancouver Book. The book I’m working on now—the inspiration for this web site—will elaborate on the events cited above, and bring the story up to date.

If you found this brief once-over-lightly look at the area’s history useful and informative, tell your friends!

Cheers,

Chuck Davis