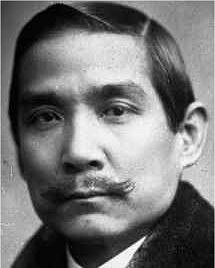

Dr. Sun Yat-sen

He is revered by Communists in China—and by Nationalists on Taiwan. His name is Dr. Sun Yat-sen and he’s considered the Father of Modern China. Sun played a leading role in the overthrow of the oppressive Ch’ing dynasty (the famous Manchus) in 1911 and was the first president of the Republic of China.

That revolution was financed by Chinese living outside China, many of them right here in Vancouver.

One Vancouverite who made one of those small, but valuable contributions to Sun’s struggle was Yun Ho Chang. He was 24 then. Yun, born in the tiny southern China village of Shek-ki in Kwangtung province in 1887, clearly recalls a 1911 visit to Vancouver by the famous revolutionary. Yun is interviewed in a book titled Opening Doors: Vancouver’s East End. (Daphne Marlatt and Carole Itter conducted the interview, with the help of interpreter Charles Mow. This has been one of my favorite local books for many years; it’s crammed with interesting stories.)

“Dr. Sun Yat-sen came to Victoria and spoke to the Chinese Benevolent Association there,” Yun recalls, “and then came to Vancouver and spoke at the CBA here. He spoke the same dialect I do and so he spoke Cantonese with a Shek-ki accent. Most people here were from Sze-Yup and didn’t understand him. They said if Dr. Sun couldn’t make them understand his speech, how was he going to get China back from the Manchus?

“They were swearing in the background while he was talking. His talk lasted for two or three hours and then he asked for suggestions. People asked him questions about his plans. He would answer in a very calm, confident tone.

“Some people contributed money on the spot. I did, too, and Dr. Sun wrote out a receipt to each person who contributed. After the overthrow, if you went back to China with the receipt, he would refund your money.

“When I went back that was just before the revolution and there was a regulation that anybody caught with this sort of receipt would be executed immediately. So I burned mine. But some of my friends were given their money back. And one man who donated $100 was later given a life pension.

“But there was a difference of opinion among people here, Those people from Chungshan were very enthusiastic about supporting him but the Sze-Yup people were doubtful. They would ask embarrassing questions like, ‘You don’t even have a ship or a gun. How are you going to overthrow a whole dynasty?’ And, ‘You don’t have any money, all you have is talk.’ But he said support would come from the people if the overseas Chinese worked hard and, when the time came, plans and cannons would be available.”

The time did come, eventually, and so did the cannons . . . but the struggle cost Sun a great deal of effort. Still, 1911 marked the end for him of a 16-year exile from China. That exile had begun in 1895 when he failed in an attempt to begin a popular uprising in Canton, the capital of his native Kwangtung province.

Between 1895 and 1911, Sun, from abroad, masterminded no fewer than 10 more uprisings . . . all but the last unsuccessful. A nice ironic touch: The successful revolt started without Sun’s direct guidance—he read about it in a newspaper in Denver, Colorado—but he returned quickly to China and in 1912 was appointed provisional president by revolutionary delegates meeting in Nanking.

His career from that point is crowded and turbulent (he had to go into exile again, as competing factions got the upper hand) and includes a period when he established a military academy administered by an ambitious 36-year-old officer named Chiang Kai-shek.)

Meanwhile, for Yun Ho Chang life also was . . . interesting.

“I went back to China in 1911, just before the revolution, and was still wearing a pigtail. This was in September. When the revolt spread to Shek-ki, we cut off our pigtails. I spent six months in my home village and during that time got married and spent three months with my wife. Then I came back to Canada. She didn’t come until 1949. I went back several times but I couldn’t bring her over without paying the $500 head tax which all Chinese had to pay. And then after 1923 she wasn’t allowed to come at all.”

In 1923, Ottawa passed the Oriental Exclusion Act, effectively prohibiting immigration to all Chinese except consuls, merchants and students. Those men, like Yun, with families still in China—the vast majority—were unable to bring their wives or children over until 1947 when the act was rescinded.

In 1949, some 38 years after they were married, Mrs. Yun was finally able to come to Vancouver and settle down with her husband.

The entire interview with Yun, and with dozens of other old time Vancouver East Enders, can be read in the Marlatt-Itter book.

![Sun Yat-Sen Garden [Image: The Canadian Enclyclopedia]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/dd1cb474-9295-42a9-b726-f7d870214d33-800x445.jpg)