The Pantages in Vancouver

Alexander Pantages is important in the show business history of Vancouver because he built two theatres here that were part of his vaudeville empire, and because of his influence on the careers of two men who were important in the Orpheum’s story: Marcus Priteca and Tony Heinsbergen. Pantages had no connection with the Orpheum himself.

Pantages’ life story reads like an adventure novel. He was a sailor, a laborer on an early and abortive French attempt to build a Panama Canal, a Klondike prospector, a guide, a bartender, saloon co-owner, boxer (short—about five feet six—but husky, he fought as a welterweight at 144 pounds), entrepreneur and showman. He could speak six languages but read and write in none of them.

He was born Pericles Pantages in 1876 on the Greek island of Andros, but started calling himself Alexander after being told the story of Alexander the Great. He ran away from home at age nine, and worked at many jobs—often at sea—and in several countries. The Klondike gold rush of the late 1890s lured the young Pantages, as it did thousands of others, to Skagway, Alaska. Seattle historian Murray Morgan has written: “When he reached Skagway, a boomtown where coffee cost a dollar a cup and ham and eggs five dollars a plate, he had twenty-five cents in his pocket. He stopped worrying about getting rich and started worrying about getting food. He took the first job offered, as a waiter.”

Pantages realized very quickly that, for him, moiling for gold in the fields wouldn’t be as much fun or as lucrative as getting it directly from other gold seekers. His showbiz career started when he persuaded the owner of a Skagway saloon where he worked to put on small entertainment events for the prospectors. A little later, around 1901, in Dawson, Pantages borrowed money from a dancer, Kate Rockwell, known as “Klondike Kate,” to run a theatre where music and variety acts helped to separate the prospectors from their pokes. Tickets were $12.50.

A website on Kate Rockwell explains why she attracted Pantages’ attention: “What made Kate famous was her flame dance. For this dance she would come on stage wearing an elaborate dress covered in red sequins and an enormous cape. She took off the cape revealing a cane that was attached to more than 200 yards of red chiffon. She began leaping and twirling with the chiffon until she looked like fire dancing around. At the end she would dramatically drop to the floor. The miners loved it. She was a hit and was named ‘The Flame of the Yukon’.”

Kate became Pantages’ mistress, but later discovered that he had married a violinist and, just as bad, skipped town without paying her back. (Note: The “Klondike Kate” most famous to Canadians was New Brunswick-born Kate Ryan—who has an earlier claim to the name.)

Pantages settled in Seattle in 1902 and, at age 26, took another important step in his vaudeville career. “He rented an 18×75-foot store on Second Street,” Murray Morgan writes, “fitted it out with hard benches, bought a movie projector and some film, hired a vaudeville act, and opened the Crystal Theater. He was his own manager, booking agent, ticket taker and janitor. Sometimes he ran the movie projector.”

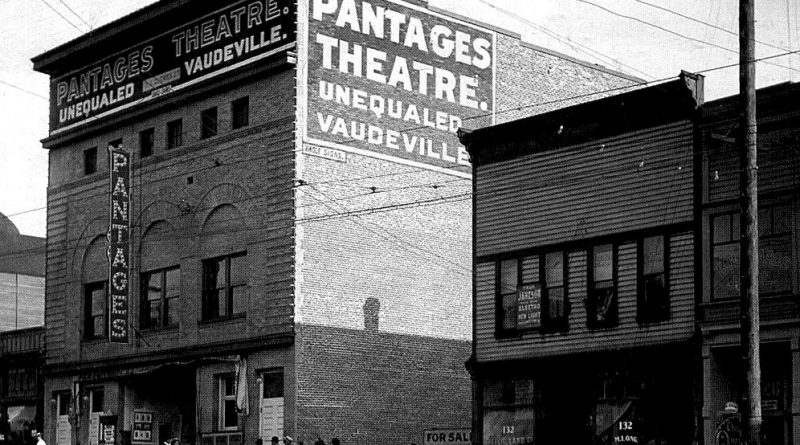

Admission was 10 cents. This was the very small beginning of the very large Pantages Vaudeville Circuit. The Crystal was successful, and Pantages became an important figure in Seattle’s vaudeville scene. In 1904 he opened a fancier show house, which he called the Pantages, the first of that name. By 1907 he had opened a third theatre in Seattle—and, on January 6, 1908, another in Vancouver. That Vancouver building is still there, the oldest theatre in Greater Vancouver, the oldest remaining Pantages theatre in North America, and one of the oldest purpose-built vaudeville theatre interiors in Canada.

Our thanks to site visitor Malcolm Page, who keeps us informed on theatre doings, for this update: The Pantages, at 152 East Hastings, whose original architect was Edward Evans Blackmore, is being refurbished and will be re-opened in 2007 by a company called City Opera of Vancouver. They are now soliciting applications from members of the Professional Theatre Alliance to become one of the resident theatre companies in the Pantages.

Malcolm adds, “As far as I can see, the final use as a theatre by the Pantages was by Tamahnous with a show called Salty Tears on a Hangnail Face, in June 1974. Then the theatre showed Chinese movies for roughly 20 years.”

Incidentally, in a February 1949 article in the Province Patrick Keatley, who knew Lloyd Pantages, says that Alexander Pantages preceded that 152 East Hastings establishment with a theatre in a rented store on Powell Street.

Image: The National Trust for Canada

Another Vancouver-based Pantages theatre later became the Majestic, then the Beacon and finally the Odeon Hastings. Construction began in 1914, but shortage of materials because of the First World War brought a halt to the work. It began again in 1916 and the theatre opened in 1917 at 20 West Hastings, boasting 1,825 seats. (Ivan Ackery, in his book Fifty Years on Theatre Row, says construction resumed in 1917 and the theatre opened in 1918.)

During its time as the Pantages this theatre headlined stars like Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel, Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth. (There is a funny photo of Ruth on the Pantages stage with Vancouver mayor L.D. Taylor crouched behind him as “catcher.”) The theatre was demolished in 1967 to create a parking lot, a move that outraged the locals and is credited by some as the spark that ignited public support for the preservation of the Orpheum. I remember going to that palatial theatre with my father in the late 1940s, when it was called the Beacon.

By 1909 Alexander Pantages was thriving, owned palatial homes in Seattle and Los Angeles, and managed or owned theatres all up and down the Pacific Coast. At the peak of his career, he owned or controlled more than 70 vaudeville theatres. Not bad for a man who could neither read nor write.

Pantages ran his circuit with a strong hand, and personally supervised his theatres’ bookings. He wasn’t interested in elevating his patrons’ tastes: he gave ’em what they wanted, and shared their tastes himself. He had an unerring skill in choosing acts his working-class audiences would enjoy. He insisted on keeping performances short so that audiences could be turned over as often as possible. His techniques made him rich.

His long association with Marcus Priteca (right), the architect of our Orpheum Theatre, began in 1910. The 35-year-old Pantages met the 21-year-old Priteca in Seattle, listened to his ideas on theatre design, and commissioned him to design the San Francisco Pantages Theater. He was so happy with the result he commissioned Priteca to design all of his theatres from that time on, an arrangement that lasted for the better part of the next two decades. The lavishness of the Pantages theatres became legendary.

Working for Pantages, in collaboration with painter/designer Tony Heinsbergen (who provided many of the lavish decorative touches in our Orpheum, including the ceiling mural), Priteca designed and oversaw the construction of more than 20 other theatres, including one in Edmonton. His largest was the Hollywood Pantages, completed in 1930 and seating 2,800—a lavish Art Deco palace that housed the Oscar ceremonies for six years in the mid-1950s.

In 1929, just before the Wall Street crash, Pantages sold his circuit to Radio Keith Orpheum for $24 million. He died in 1936, aged about 60.

But there were plenty of other Pantages’ to go around. A nephew of Alexander’s, George Pantages, came to Vancouver and managed the original Pantages Theatre. He later managed the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles. George was succeeded in Vancouver by his brother Lloyd. Then Peter Pantages, yet another nephew of Alexander’s, also came to Vancouver and settled here. For locals at any rate he became the most well known of them all, as the founder of the Peter Pan Cafe on Granville Street. That cafe became a city landmark, and the home of many thousands of birthday parties, christening and wedding celebrations. But Peter, whose passion for swimming was life long, was also the founder in 1920 of Vancouver’s famous Polar Bear Club, still extant, the members of which dash into the frigid waters of English Bay every New Year’s Day. The first event drew five hardy souls. Today, more than eight decades later, thousands congregate to watch the braver among them leap into the chilly bay.