Biz-Biz 1910

Seeing the name “Tehuantepec” in a newspaper headline about the Vancouver Board of Trade was bound to excite our curiosity. It proved to be the location of an early Mexican railway, and was one of the subjects discussed at the January 4, 1910 regular monthly meeting of The Board. [This railway connected the Atlantic and Pacific oceans across the narrowest part of Mexico; the Panama isthmus is farther south, but in 1910 the Panama Canal was still four years away.]

We’re detailing the story at some length here because the basic subject—freight rates—was so crucial to early Vancouver business; even a hundred years ago local merchants felt we were being screwed.

The Mexican railway referred to in this story had finally (after several abortive attempts) opened to traffic in January 1907.

Why was it being talked about at the Vancouver Board of Trade in 1910?

It seems the Grand Trunk Pacific and Canadian Pacific railways were charging local (i.e., higher) rates from inland shipping points to Montreal or Halifax on goods shipped to Vancouver via the Tehuantepec route. The railways’ export rates were cheaper, but Vancouver business men were not getting those rates. The Elder-Dempster Steamship Co., which operated boats from eastern Canada to the eastern terminus of the Tehuantepec line, which was on the Gulf of Mexico, wanted the support of The Board in its application to the Railway Commission for an easing of the rates.

The Board was happy to oblige.

Entitled to the Same Rates

“The sentiments of the board crystallized,” wrote the Province of January 5, 1910 (Page 7) “in the following resolution, submitted by Mr. W.H. Malkin: ‘Whereas goods shipped from eastern Canadian points destined for Mexico are carried to Montreal in summer and to Halifax in winter at a special export rate, it is the opinion of this board that the same rate should be accorded to goods from such points when such goods are destined for British Columbia via Mexico.’

“The steamship company,” the Province continued, “pointed out that the discrimination against eastern Canadian business men gave an unfair advantage to English and German manufacturers. Mr. Malkin said the matter was an important one for all western business men and threatened to destroy the advantages so fondly anticipated by the establishment of the Mexican route. He considered that they were as much entitled to the export rate from inland eastern Canadian points as Mexican business men who imported from the same points. The question was one which should be referred to the Railway Commission.”

More Ammunition

Capt. Worsnop of the Canadian-Mexican Steamship Company, (a Board member), also complained about the railways’ fees, saying that the original understanding was that “goods shipped across Mexico to Vancouver were to enjoy the export rate.” He had a letter from the Elder-Dempster firm (cited above) that explained that while the Intercolonial railway—the Trans-Mexican line—was willing to quote the export rate, “the ratemaking power on shipments to the seaboard was in the hands of the two leading Canadian railway lines.” [They would be the aforementioned Grand Trunk Pacific and Canadian Pacific.]

Nails

Then member Mr. Morrison [these early stories frequently leave out first names] of the British Columbia Nail Company spoke up.

There was another side to the story.

He pointed out that “any further reductions of rates on manufactured goods shipped from the east would not tend to encourage the development of manufacturers on the coast. His company had to face keener competition as a result of a sweeping reduction in the rail rates on similar goods shipped from Eastern Canada.” To this argument, the paper reported, Malkin replied that “no doubt Mr. Morrison favored getting in his raw material at the lowest terms, to which Morrison responded that his raw material was imported via the Tehuantepec route and by the Blue Funnel boats.”

[A parenthetical note: the Blue Funnel line was a famous English firm, established in 1865. Elder-Dempster was even older, being established in 1852 as the African Steam Ship Company. Blue Funnel would later take over the older firm.]

Pilot episodes

The January 4th meeting also looked at an initiative of the provincial government to remove the pilotage station from Vancouver to Victoria. The Vancouver Shipmasters’ Association had written to The Board, protesting the change and asking for support. Member Charles Tisdall, MLA (and future mayor), said he would write the minister of marine “for details of the changes recommended in the department by certain unknown individuals.”

Tisdall also made a strong protest “against any movement that would result in making the Vancouver pilots establish their homes in Victoria.”

Capt. Worsnop said some change was needed. “At present they had to deal with no less than four pilotage authorities, and it was not uncommon for his steamers to have two or three pilots on board at once.

“At every port visited, Victoria, Vancouver, New Westminster, Comox or Ladysmith, new pilots had to be engaged. On her last trip the Georgia paid over $500 in pilotage fees, an amount equivalent to seven per cent of her gross earnings on the trip, and in other instances the amounts had been even greater.”

The difficulties of pilotage, Worsnop said, were virtually over after reaching Point Grey. “Pilotage fees into Puget sound did not exceed $250,” he said, “as compared with an average of $400 for every ship that came to Vancouver.”

Delicate Situation

Member R.H. Alexander was, he told the others, in a delicate situation: he was the chairman of the pilotage board. “Personally,” the Province wrote, “Mr. Alexander did not favor making one pilotage board for all British Columbia. A prior experiment in that direction had not proven satisfactory. It would be necessary to maintain two staffs of pilots at Victoria and Vancouver. Many vessels coming to Vancouver did not touch at Victoria . . . While the tax for a pilot for each port seemed heavy, it should be remembered that the [ships’] owners got a good service. Vancouver and New Westminster pilotage districts had been separated, as it was found necessary to have independent pilots for navigating the Fraser.”

No Storage

Worsnop told The Board that his company—the Canadian-Mexican Steamship line—had “practically made bookings for wheat exports of 10,000 tons to be shipped from Vancouver to Mexico between now and May.” But then he had been advised from Calgary that the shippers “expressed their inability to ship this way owing to the lack of permanent storage facilities in Vancouver. The grain in question had since gone east via Fort William.”

W.H. Malkin spoke up at this point. He had been assured by E.H. Heaps, another Board member, “that a new company hoped to be able to provide these facilities in Vancouver to handle next season’s crop.” [In the event, Vancouver didn’t get a grain elevator until 1914. It would be financed by H.H. Stevens, encouraged by the construction of the Panama Canal.]

Other matters

The January 4 meeting dealt briefly with insurance: The Board decided to send a wire to Ottawa protesting against the insurance bill then before the Senate. “The measure,” wrote the Province, “tends to exclude non-board companies from doing business in Canada. [The “board” in this case was the board of fire insurance underwriters.] The bill has already passed the house of commons. It provides that all unlicensed companies must pay 15 per cent of their premiums to the government. Mr. H.G. Ross defended the measure, which in turn met with the opposition of Mr. Malkin, who declared himself in favor of the freest competition in the insurance business.”

[A note here on style: the newspapers then didn’t capitalize the words “Senate” or “House of Commons.”]

A letter from Ottawa asked an expression of opinion relative to a bill before the house providing for an eight-hour day on all public works. No further details on that in this report.

And the Board secretary was instructed to tender an invitation to the prime minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, to be the guest of The Board at a complimentary banquet. It seems the PM had abandoned the idea of a trip abroad in favor of a visit to the Pacific coast in the summer.

In the event, Laurier would make it to the coast that summer. It was he, in fact, who presided at the official opening August 16, 1910 of the first Vancouver Exhibition, what we now call the Pacific National Exhibition, the PNE. [There had been a “soft” opening the day before.] The PM drew big crowds. He had come all the way from Ottawa to open the fair, and 5,000 of us showed up to see him from a population about one-twelfth of what it is today. Admission to the fair was 50 cents, fairly hefty at a time when the average weekly wage for a Canadian production worker was about $9.50.

Long Letter

There was a long and eloquent letter from members of The Board’s committee on freight rates published in the Province of January 17, 1910 (Page 17).

Excerpts:

“There can be no question that we are anxious to have another transcontinental railway through British Columbia, and that no line would be more welcome than the Canadian Northern as Messrs. Mackenzie and Mann have shown such energy and ability as to deserve the admiration and encouragement of every loyal Canadian, and their willingness to meet conditions by reducing rates is also known and appreciated.”

[A note of explanation: William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, both Canadian born, had spent much of the late 1890s in buying up small Manitoba railway lines, and had established the Canadian Northern in 1899. Their intent was to provide competition with the CPR, and they began by providing a link between the prairie provinces and Fort William/Port Arthur—Thunder Bay today—on Lake Superior. This line would permit the shipping of western grain to European markets as well as the transport of eastern Canadian goods to the West.]

Back to the letter.

“The board of trade showed that to most points it cost nearly 50 per cent more on the average to ship certain goods eastward from Vancouver per mile, than it does to ship the same goods from Montreal or other eastern centres westward . . . the rates from the east westward are so much lower as to enable eastern merchants to send goods two or three times the distance for the same cost.

“It stands to reason that if the Canadian Northern would agree to give us the same or nearly the same rates eastward as westward they would create new business for the railway company . . .

Easier route

“The Canadian Northern railway assures us that they have secured a very low grade, passing through a country much more favorable to railway building and maintenance than that of the CPR, and that they will be enabled to haul three of four times the weight per engine than the CPR can . . .

“As an ordinary business proposition it would appear wise policy on the railway’s part to grant this reduction even without any consideration of government assistance, and it does seem to us that the government, in guaranteeing bonds to the extent of $21 million, should obtain the insertion of such a clause as proposed and we do not doubt that having so ably protected the interior of the province in the past they will do so in this instance to the fullest extent possible.

“There is still another reasonable view to take, which is, that shippers on the Pacific coast are entitled to the same rates eastward per mile to a half-way point over a transcontinental line as it charged on the same line westward from the Atlantic ports to the same point, and should the government arrive at a settlement on such a basis as this they would at one masterly stroke have solved the problem of years.”

Second Telephone Company?

A short article in the Province for January 31, 1910 (Page 11) tells us that the Council of The Board had passed a resolution opposing the granting of a second telephone franchise in the city. The existing franchise was held by the British Columbia Telephone Company, today’s Telus. The resolution would be considered at the regular meeting February 8th.

That meeting—described on Page 23 of the Province for February 9th—heard from Charles Woodworth, representing that second company. Despite laying out what he presented as the benefits of his proposal, he was unsuccessful, with The Board voting 15 for not granting the franchise and seven in favor of granting it. Of course The Board didn’t have the power to enforce that ruling, but the meeting made it clear the chances for a second franchise were slim to none.

An interesting excerpt from the newspaper’s report: Woodworth said that the fees his company would charge “would be as low as those of the present company, and their system would be modern in every respect. When they acquired branches in Vancouver they proposed to extend their line to North Vancouver, New Westminster, and other outlying places connecting with the system to the south. [Presumably a reference to Seattle, which had a single company and apparently leaned toward keeping it that way.] The result of their installation would be that instead of patrons being able to talk to six or seven thousand people, they would be able to talk to 13,000.”

B.C. Telephone’s George Halse—he later became president and then chairman of the company—told Woodworth, who had hinted at inefficiencies in the present company’s system, that “he was prepared to bet $100 with him that he could not show a system which would equal that of his company in any city of similar size.”

To which Woodworth responded: “I will take your money.”

Long Waits

Member W.A. Akurst spoke up, saying he knew personally of persons who had been trying to get telephones in their houses for nine months. “If the present company was not enterprising enough to anticipate the requirements of a growing city it was time they had a company which would look after their requirements.”

[Note: we have a hunch that the spelling should be “Akhurst.” W.A. Akhurst established Akhurst Machinery in Vancouver in 1938. We have a strong feeling there is a connection, and we’re checking!]

H. Bell-Irving said he believed the telephone company was doing the best it could. He thought The Board must recognize “that with the extraordinary extension going on in the city it was exceedingly difficult for the company to keep up to the mark every time.”

Member Mr. Cotterell wanted to know, said the Province’s report, “what should be considered a reasonable time to instal a telephone in the business district.”

Mr. Halse: “About eight hours.”

Mr. Cotterell responded that he had made application for a telephone on December 2, and it had not been installed until February 3. “If the present company could not instal business telephones in less than two months, and residential phones in less than nine months, he thought it was time they had another telephone system here . . . It frequently occurred, he said, that telephones were out of order for four or five days at a time and no allowance was made therefor by the company.”

Ewing Buchan weighed in, observing that the failure to keep pace with the growth of the city was common to other enterprises. “The street car time table,” Buchan said, “in some cases was just as slow as it was 10 years ago.”

Growth!

Bell-Irving and Buchan had a point: the population of Vancouver city in 1901 had been 27,000. By 1911 it would be just over 100,000. The population of the city was climbing by more than 7,000 a year! And that wasn’t counting the growth in the suburbs, also serviced by the telephone company: Burnaby’s population in 1901 was 750; by 1911 it would be more than 13,000. New Westminster went from 6,500 to 13,000, the North Shore from 365 to 8,000 and so on. The city’s 1901 suburban population was about 14,000. By 1911 that would climb to more than 62,000.

Better than Seattle

Board President E.H. Heaps thought the Vancouver telephone system was better than that of Toronto, and he was sure that it was a great deal better than that of Seattle. “While it might not be all that they would like, still allowances should be made for a company that had commenced when the city was young. Trouble due to the rapid expansion of the city was being experienced in many lines of business.”

The resolution not to approve of a second telephone company was put and carried.

Those were the (mail) days!

Member H.A. Stone told The Board at the February 8th meeting that the postmaster had advised him that it was the intention of the postal department to “inaugurate an improved delivery service in the city so that the need for using boxes might be eliminated as much as possible. He understood that deliveries were to be made at 8 and 10 o’clock, and that there would be two deliveries in the afternoon . . . Mr. W. Dalton said that a system of letter boxes on the street cars had proved most advantageous to business people in the old country and might perhaps be introduced profitably here.

“Mr. Stone said he would take it up with the postmaster.”

[This system of using the streetcar to carry the mails was new to us—but only to us! And the “old country” wasn’t the only location. A check of the Internet showed that it was happening in Chicago in 1874, and had been used in Philadelphia streetcars from 1865 to 1867, “and found a great public convenience; but it appears that the conductors considered them an annoyance, while the companies did not find any profit in them, so this good institution did not spread. We have no doubt that when the New York post-office is completed, the proper authorities will see the advantage of placing letter-boxes on all the lines which have their terminus at the new post-office. If we take into consideration that about a dozen lines have their terminus there, it is evident that no better means could be devised for a rapid expedition of letters from all parts of the city . . . Indeed, the convenience for the dwellers along these lines would be very great if they could drop their letters into the cars passing there every few minutes.” (Manufacturer and Builder, March 1874.)

Dreadnoughts

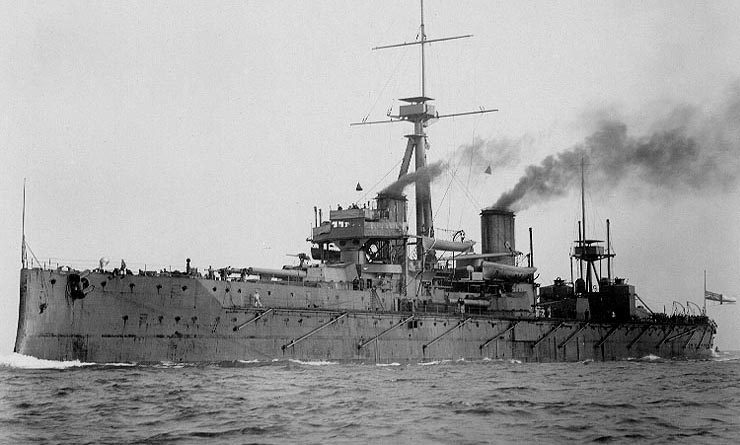

H. Bell-Irving proposed a resolution at the February 8 meeting that “Canada should authorize the immediate construction of one or more Dreadnoughts as an assistance to the mother country against the German peril. He claimed that the general opinion of Canada was in favor of such assistance being given, and that that assistance should be substantial and not a sham.”

[Dreadnoughts were named for the first of the class, defined this way: “a type of battleship that derived its name from the British warship Dreadnought, launched in 1906. This ship, which marked a new era in naval construction and made obsolete every battleship afloat, bettered its predecessors in displacement, speed, armor and firepower. It had a displacement of 17,900 tons, a speed of 21.6 knots, a cruising radius of 5,800 sea miles, and was protected by armor eleven inches thick. It was the first battleship to be driven by turbines. Its main battery consisted of ten twelve-inch guns, making it the first all-big gun ship in the world. After its launching and until the First World War, every battleship built with a main armament entirely of big guns all of one caliber was considered to be in the Dreadnought class.” Source here.]

There was too much opposition to the resolution, mainly on the grounds it was too political. The Commons itself was split on the question. “The matter was now in the hands of the government,” said Charles Woodward (who had voted against a similar resolution when it appeared before The Board on a previous occasion), “and they had better facilities for getting knowledge as to what was necessary than the board of trade could hope to possess.”

Other objections arose and with Bell-Irving’s consent the resolution was allowed to die. Still, the March 9, 1910 Province, in coverage of outgoing President E.H. Heaps’ year in office, had this: “At a special meeting held 24th March last, the board put itself on record by telegraphing Sir Wilfrid Laurier the opinion ‘that the Dominion of Canada should at once offer to the Imperial authorities a sufficient sum to build a modern Dreadnought of the strongest type.”

Annual Meeting, March 8

At the annual meeting of The Board on March 8, 1910 Ewing Buchan became president, succeeding E.H. Heaps.

And a resolution was approved and forwarded to the city council advocating that the city should retain control of the bed of False Creek, and that if the riparian rights have to be acquired that these should be expropriated by the city. [Riparian right: a right (as access to or use of the shore, bed, and water) of one owning riparian land—land on the bank of a river, lake or tidewater.]

A review of the previous year’s activities showed that the CPR’s Agassiz train had been reinstated, and that regular Great Northern service had been established on the south bank of the Fraser. The Board had lobbied persistently for both results. They were pleased, too, that a daily CPR train had been established between Vancouver and Revelstoke. The Board had also argued for more cruisers “for the more adequate protection of our most important deep sea fisheries,” and it was “gratifying to know” that that had also occurred.

Highway to Alberta . . . and mail to France

The Board sent a resolution to the provincial minister of public works saying that “steps should be taken to connect the various sections of roads in the province so as to form a continuous highway from the coast to Alberta.”

A petition had arrived from La Chambre de commerce du Montréal “urging the establishment of two-cent postage between Canada and France . . . as a further step towards the introduction of universal penny postage.” The Board endorsed the petition.

Litany

Outgoing President Heaps ran through a list of the subjects that had received the attention of The Board in the year of his tenure:

- Reduction of freight rates to the Yukon

- United States lumber duties

- Day Light Saving Bill

- Coinage of Canadian gold coins, silver dollars and nickels

- Suggestion to appropriate 500 acres of Point Grey reserve as part of university appropriation fund [A note: We believe the reference here is to revenues to be received as a result of selling or leasing parcels of the Point Grey lands, said revenues to be stored up to help finance the proposed university. Point Grey as the actual site of the university was not yet decided upon.]

- Suppression of professional gambling on race tracks

- The necessity for a new city hall

- Opposition to a second telephone system in the city

- Support for a bridge over the Second Narrows. [There was a note of hopefulness on this issue in 1910, but such a bridge was still many years in the future: 15, to be exact.]

Guests

Heaps recalled with pleasure visits by several distinguished guests. Lord Strathcona, for example, had visited in August of 1909 and had been the guest of honor at a banquet in the Hotel Vancouver on August 31. The Board also “had the pleasure of entertaining Sir Charles Rivers Wilson, President [Charles] Hays and other leading officials of that company [the paper doesn’t name the company! It was the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway] as their guests while passing through the city, and received from them the assurance that after the completion of their main line to Prince Rupert a branch from some convenient point will be built to Vancouver.”

[The Grand Trunk’s plans didn’t pan out. Prince Rupert was to have been a great metropolis, a rival to Vancouver, that Charles Hays planned to build at the western terminus of his railway. His plans included a fine hotel, 14 stories high, decked out in all the best chateau-style trappings of the day, and designed by Francis Rattenbury. Rattenbury is the famous architect who gave us Victoria’s Empress Hotel and the provincial legislative buildings, as well as Vancouver’s courthouse, now Vancouver Art Gallery. Allan Wilson, Prince Rupert’s chief librarian, found and purchased a complete copy of Rattenbury’s drawings for the hotel, and says it could be built today. “Had it been built,” Wilson says on this website, “it would have rivaled the Empress, Toronto’s Royal York and Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier in the pantheon of great Canadian railroad hotels. Unfortunately, Hays, the driving force behind it and most of the rest of Prince Rupert in those early days, made the fatal mistake of booking space on the Titanic on his way back from England in 1912. Over the years, the story circulated that the plans for the hotel went down with him, which wasn’t true.”]

Shaughnessy

Heaps also cited the pleasure of a special interview with Sir Thomas Shaughnessy, president of the CPR, on September 22, 1909, “at which the principal subjects discussed were the building of elevators or other provision for the storage and shipment of grain at Vancouver; the desire of better freight rates from this coast, particularly to the Boundary country and Alberta; and the question of assisting immigration to this province by the granting of more favorable transcontinental rates for immigrants, all of which the [Board’s] council was assured would receive careful consideration . . .”

He briefly reviewed the mining industry, which had reached a production of $24 million in 1909, an increase of about 10 per cent over the previous year, but below the average of the years from 1906 to 1908. “There was a considerable reduction in the market value of copper produced, which was more than made up in coal and zinc.”

The forest industry was coming along famously. “The lumber produced in 1909,” Heaps reported, “is estimated at $12 million, which is equal to the best year in the history of the industry, and the outlook for 1910 is so bright that a considerable increase may be anticipated in all its many branches . . .” Still, mill owners were complaining there had been little or no margin of profit for them, but that the retailer gets the lion’s share. “In the interests of this important industry,” Heaps advised, “it is desirable that, without increasing prices, a reasonable proportion of profits should be received by all engaging in it.”

[It’s interesting that mining made twice as much in 1909 as the forest industry.]

Fishery

Fisheries did not tell the same story of success. The Fraser River pack of salmon was 567,203 cases, the Province reported (March 9, 1910), compared with 877,136 cases in 1905 and 900,252 in 1901. Causes: adverse weather, disappointing conditions, regulations “and a closed period of 42 hours, which was observed.” That was in contrast with a 36-hour closure to Washington State’s fishermen, a closure that was not observed. “The Puget Sound catch was greater than in 1905.”

The Skeena River pack was down to an even greater extent, with 140,739 cases in 1909, compared with 209,177 the year before. “Federal regulations are blamed for this small pack . . .”

The Pacific Coast catch, Heaps reported, “is estimated at five million cases. It seems conclusive that our canners are not securing a reasonably fair proportion of the fish that should come into our waters.”

[Fisheries and Oceans Canada has a page of recent statistics on the BC fishery here]

Fruit growing

There had been a bad frost and that had hurt the fruit farms of the province, but “as great headway has been made in new plantings the future prospects of this growing industry are most promising. The proposition to hold a Canadian National Apple Show in Vancouver this fall is deserving of every encouragement . . . Tobacco is now being grown with reported good results in the Okanagan.”

Manufacturing

The federal government, Heaps said, had estimated the value of the province’s manufacturing industries for 1909 at $30 million. New companies chartered during that year had “authorized capital aggregating $48 million, not including extra-provincial companies, and after making liberal allowance for unlikely schemes this shows an active interest in industrials.”

Then he made a suggestion that’s interesting for its foresight: “It seems,” he said, “at this stage of the city’s progress desirable that a special branch of the Tourist Association, or a new Industrial Development Association should be formed, to carry on the special work of encouraging industries.” That, of course, is what the Vancouver Economic Development Commission does today. You’ll find their website here.

Special Rates

President Heaps noted that Winnipeg city council was “preparing to announce special low rates for electric power to manufacturers, there being under construction a municipal plant for that purpose. Vancouver cannot afford to be behind in such matters.”

Suggestion: A Department of Agriculture

On the subject of “the preparation of agricultural lands for settlement,” Heaps thought steps should be taken to organize a Department of Agriculture and Immigration. “I think it is a matter of regret,” he said, “that no action has yet been taken by the government in the direction suggested. Since last May the imports of agricultural produce has increased from 7 to 11 millions. [We assume he’s referring to dollars.] I purposely make this subject my last word to you as it was also my first as your president, and again to remind you how as a province we are chiefly dependent on our three great natural industries of lumbering, mining and fisheries . . . It is true $4 million is to be devoted to public works, $117,000 for agriculture, and a liberal allowance for surveys, but in the details of these no suggestion is made of even endeavoring to find some practical means of encouraging settlement by clearing lands, either owned or which could be sold to settlers, or by any other means . . .”

New digs?

There was a committee considering an improvement in The Board’s quarters. They hoped “to put before you a proposal that we trust will meet our requirements for many years to come.” At its May 17 meeting The Board learned from President Ewing Buchan that “arrangements had been completed for a ten years’ lease of the entire top flat of the Molsons Bank building at a rental of $150 a month.” [That building was at the northeast corner of Seymour and Hastings, where Harbour Centre sits today.]

Membership on the roll for March, 1909 was 163. There had been 73 new members during the year, two members had died and four retired, leaving a present membership of 230. There had been a total of 15 Board meetings with an average attendance of 30. Number of Council meetings: 15. Average attendance at these: 10.

New Companies Act

For those of you thirsting to know the provisions of the new Companies Act of 1910, you’ll find a summary—prepared by William Skene, the Secretary of The Vancouver Board of Trade—on Page 7 of the Province for May 9, 1910. They were largely concerned with “extra-provincial” companies, which would now need a licence to do business in the province, and set out a standard of licence fees for such companies.

The May 17 meeting of The Board (cited on Page 7 of the Province for May 18) led to a warm discussion about the Act, with some members saying they were unfamiliar with the bill “and mildly intimated that it should have been given greater advertisement before it was passed in the legislature.”

Member Charles Tisdall, who was a Vancouver MLA, informed the meeting that the Act had been fully discussed in the newspapers and also in the House before it was passed. “I do not think that it is right for some of the members to profess ignorance about it,” Tisdall said.

“Objection was taken to the Act,” the newspaper reported, “on the ground that it would prevent a free interchange of trade between British Columbia and other provinces of the Dominion and also with the Old Country and the continent of Europe.”

More below in coverage of the June 7 meeting.

The King is Dead, Long Live the King

The regular meeting of The Board for May 10, 1910 was adjourned with no business conducted out of respect for the memory of King Edward VII, who had died May 6 at age 68 after a series of heart attacks. He had reigned since 1901 when his mother, Queen Victoria, died. Edward was succeeded by his second son, who became George V. (George’s older brother Albert had died in 1892.) The president of The Board, Ewing Buchan, gave the tribute and concluded: “Although we mourn the death of the illustrious father, we are especially favored by Providence in having his son George V to reign over us—a sovereign whose intimate acquaintance with all parts of the Empire has made it possible for him to follow in his footsteps. May he live to see the realization of his father’s ideal of unity of Empire, universal peace and the amelioration of mankind.”

Transportation Bureau

The subject of freight rates and other transportation matters was deemed so important to the prosperity of the city and the province that at its May 17, 1910 meeting The Board approved the “inauguration of a Transportation Bureau in connection with the Board of Trade to be constituted as a permanent department in charge of a special paid secretary.”

The provincial government had agreed to financially assist The Board. They were as anxious as The Board to see equal rates charged eastward and westward on the transcontinental railway lines. The government had actually brought suit against the CPR, but later dropped the suit because it had been unable at the time to prove discrimination on the part of the railway.

The Board had asked the railway for comparative expenses and figures, and had been rebuffed, and were now applying in Ottawa for a formal order from the railway commission.

Seattle had such a bureau within the city’s Chamber of Commerce, headed by a man named W.A. Mears—who had been brought up to Vancouver and interviewed by The Board’s freight rates committee—and it was the suggestion of the freight rates committee that Mears be engaged and that he be assisted by an advisory expert, Vancouver lawyer W.A. Macdonald, KC.

South Vancouver denied support

At the May 17 meeting The Board’s committee on railways and navigation advised against endorsing an application of the South Vancouver Board of Trade to the federal minister of public works to undertake dredging operations on the north arm of the Fraser River. [A fast reminder: South Vancouver was a separate municipality in 1910, would not become part of Vancouver until 1929.] “It was pointed out,” the Province reported, “that it would be ill advised for the Vancouver board to support such a project while the necessity of dredging the First Narrows was such a pressing one.” The committee’s report was adopted.

(By the June 7 meeting The Board had received a letter from the minister of public works, William Pugsley, stating that the government had called for tenders for construction of a dredge to work at the First Narrows.)

More on the Companies Act

The June 7 meeting of The Board spent most of its time on the question of the Companies Act. A petition had been received from a number of manufacturers’ agents protesting against the act—which required that companies from outside BC would need a licence to operate here, and would pay fees associated with that licence—and it was moved that their petition be endorsed. A member, Mr. Ramsay, thought the Act equalized matters and gave local manufacturers a fair chance with outside firms. Before The Board passed on the petition, he said, the other side should be heard.

Member George Campbell, arguing strongly against the Act, claimed that 75 per cent of the goods sold in British Columbia were manufactured outside the province. Other provinces had similar acts on their statutes, he said, but they did not enforce them. H.A. Stone said that “if the act worked any hardship it was on the smaller companies who would be called upon to pay the same amount as the large companies.”

“Summed up,” reported the Province (June 8, 1910, Page 4), “the views of the opposition people were that the private individual could do business without paying a licence while a limited company was liable. In this, the Act was discriminatory and prevented merchants buying in the cheapest market.”

A Bad Reputation

Member R.H. Alexander, a former president of The Board, said “This will strike at the interchange of commodities and give British Columbia a bad reputation. I can not see the object of harassing the business people who sell goods here. One of the most serious points is that a firm which is not registered has no protection in the courts.”

There was so much discussion, said the Province, that it was decided to refer the whole matter to the committee of trades and commerce to bring in a report before July 1.

Ladner line

“Messrs. Ladner and Fisher,” the newspaper said, “came as a deputation from the Ladner Board of Trade asking the Vancouver board to support a petition to the British Columbia Electric Railway Company for a direct line from Ladner to Vancouver. The delegates pointed out the possibilities and resources of their district in glowing colors. Ladner was only 13 miles from Vancouver in a direct line, but 40 miles on the present route.

“The route suggested in the petition is along Number Five road, across Lulu Island to the north bank of the south arm of the Fraser at Woodward’s, thence by a bridge or ferry to the nearest point on the south bank, and then to the village of Ladner and on through the centre of the district.

“In speaking on behalf of the petition Mr. Ladner said a direct line would enable Ladner district to supply Vancouver with fresh produce and would do wonders for the country. The value of the produce of the district last year was: grain $250,000; hay $240,000; milk $90,000; eggs $18,000 and fruit $20,000.”

Their petition was heartily endorsed.

[Regrettably, that BCER line to Ladner was never built. The little Delta community would be served by the Great Northern Railway.]

Image, top: The Royal Navy‘s revolutionary HMS Dreadnought, which gave its name to the type, underway, circa 1906-07 [Wikipedia]

![Miss Emily Edwardes on trip from Vancouver to Seattle, to visit Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition circa 1909 [City of Vancouver Archives CVA 371-3153]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/b98cf4fb-ca7f-468e-ab59-5d9b01363b9b-A71191-390x205.jpg)

![Hotel Vancouver [CVA 677-951]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/d6b46716-9d1a-46d2-bf48-612070ae88f4-A02796-390x205.jpg)

![Canadian Pacific Railway arrival of the first through train at the seabord of British Columbia circa 1886. Jonathan Rogers of the Rogers Building arrived on this train. [City of Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Can P2]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/07a12556-a728-4c08-97c9-ade469f12459-A25308-1-390x205.jpg)