Major James Skitt Matthews and the Vancouver City Archives

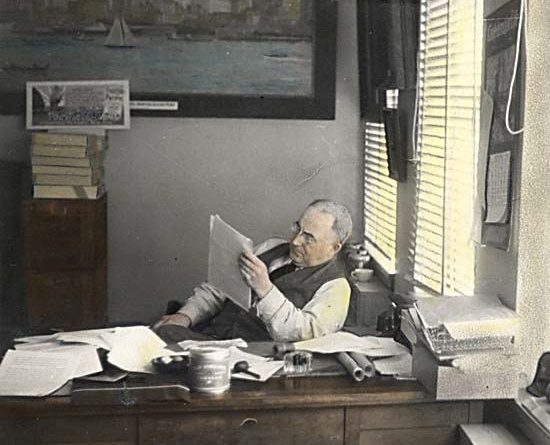

Major J. S. Matthews, adventurer, innovator, and first archivist of the city of Vancouver was born September 7, 1878 in Wales. He was a natural archivist, keeping meticulous track of his activities and of those around him who he thought were making an impact on society.

It was a short step for him to start collecting general historical material from others in Vancouver. As the collection grew, he developed his own cataloguing systems, in the end amassing more than 500,000 photographs and hundreds of civic records and personal papers.

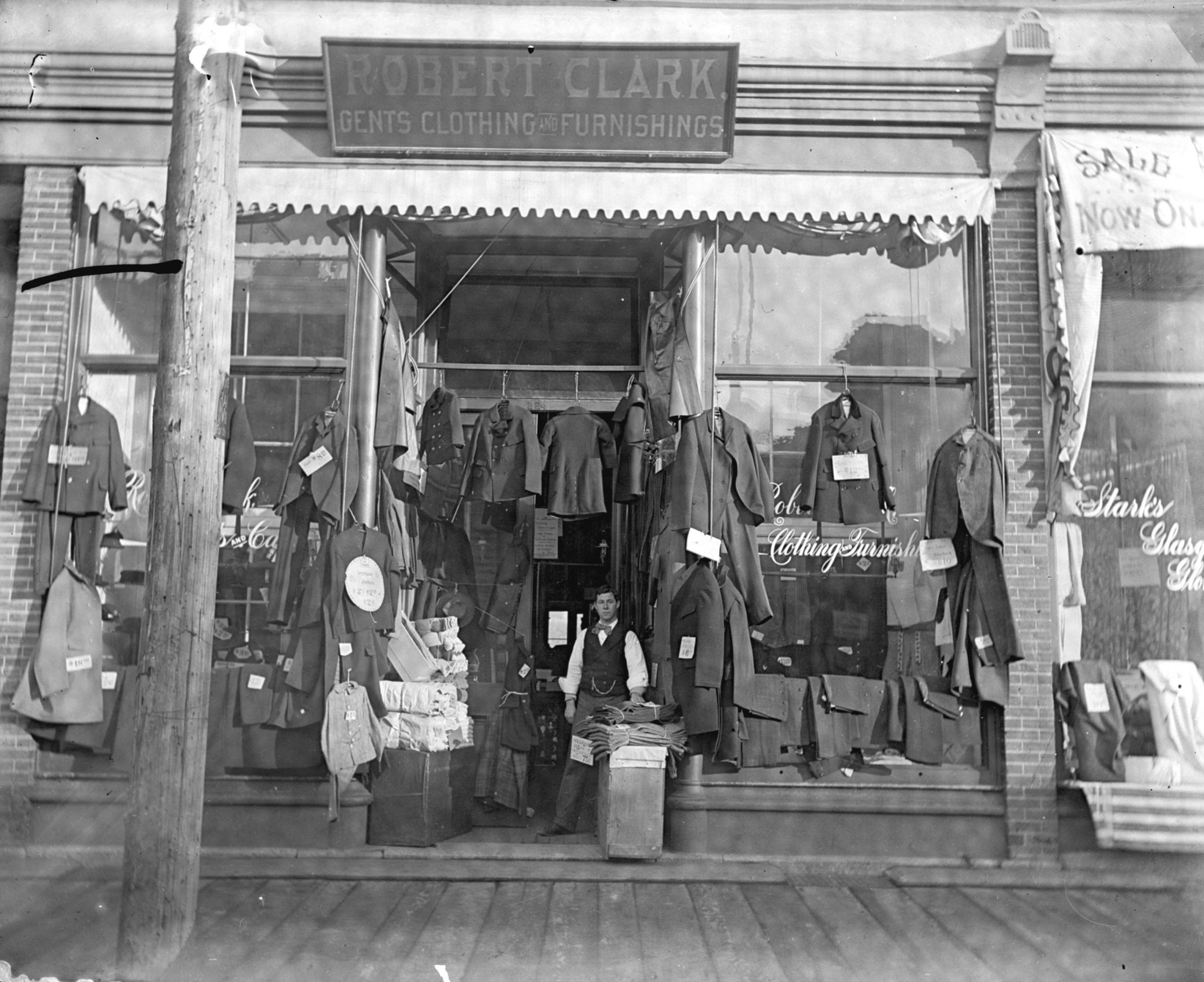

After graduating from grammar school in Auckland, New Zealand he worked as a timber clerk. In 1898 he sailed for the United States “to make his fortune.” After arriving in San Francisco, Matthews moved north along the west coast, staying briefly in Tacoma, Seattle and Victoria. There he joined up with Valentia Maud Boscawen, his fiancee, who had arrived from New Zealand. They came to Vancouver, fell in love with the city and its surroundings, and decided to make it their home.

Imperial Oil was the first oil company in British Columbia and installed Canada’s first gas station in Vancouver, about 1907. Matthews’ work for the pioneering firm had started in 1899; during his 20 years with Imperial he worked as a clerk, a travelling salesman and manager of various aspects of the provincial operation.

The Matthews family doubled in 1900 with the arrival of twins James and Herbert, and the next year their third son Hugh was born. In 1902 Matthews fell ill with typhoid and was in Vancouver General Hospital for three months. There he met the woman who years later would become his second wife.

After recovering, Matthews was frequently out of town because of his work for Imperial Oil, or on militia duty during the miners’ strike in Nanaimo in 1913. He had joined a local militia unit in 1903 but when war broke out was transferred to the regular armed forces, serving in Europe from February 1916 to May 1918. Matthews led the first and second waves of a trench attack near Ypres, becoming something of a hero. Later he was invited to take tea at Windsor Castle because of his development of “fire cubes,” eventually used by the British army. (While he was in hospital in London recovering from war wounds, Matthews conceived of a method of compressing paraffin wax and sawdust into walnut-sized pellets, which could then be ignited and give off enough heat to boil a quart of water. He called them “Fire Cubes”. The Anglo-American Oil Co. made and sold millions, but without profit. Then the army’s commander-in-chief, Earl Haig, ordered Matthews to supply enough for one army to test in the trenches. But then the war ended and demand for the “Fire Cube” flickered out.) Matthews also served as the deputy returning officer in Belgium during the Canadian federal election of 1917. By the end of the war he was a major—a title he used until his death.

Matthews returned to Vancouver in 1918 to an estranged wife, but before their divorce he was able to persuade Maud to accompany him on a tour for the federal government to promote the sale of Liberty Bonds. Two years later, now free, he married Emily Eliza Edwards, his nurse of nearly 20 years earlier. Incidentally, Emily is credited as the co-founder of the City of Vancouver Archives, but little is known about her.

After the war Matthews began his own business as a scow-owner and tug operator, taking as business partner his younger son Hugh. Two years later Hugh was killed in an elevator accident at work. In 1924 Matthews closed the towing business, briefly managed Canada Western Cordage, then retired.

With his working days at an end, Major Matthews began to devote himself to collecting and recording Vancouver history. He ran unsuccessfully for the Park Board in 1927 and 1928, when he was also director of the Arts, Historical, and Scientific Society (predecessor to the museum).

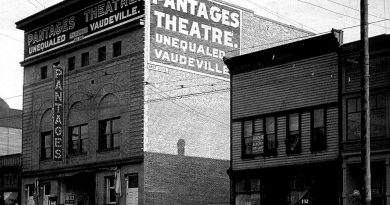

After filling every available space in their Kits Point home with city memorabilia, Matthews obtained space in the attic of city hall—a room that came to be called the Deserted Chamber. There, in those early days of the Vancouver archives, he worked in a room that was cold, dark and dirty. He called it a disgrace, and enlisted the support of public figures for a better location. In 1933 the archives moved to the Holden building on East Hastings Street, then into the new city hall, and then into the main library, before finally relocating to its current location in Vanier Park.

For many years Matthews was embroiled in controversy with the Library Board over the ownership and organization of the documents he had collected. The city’s position was that official recognition of the archives in 1932, along with an honorarium to Matthews of $30 a month, amounted to ownership of the material by the city. Matthews disagreed and moved the collection back to his house. After weeks of wrangling, he was appointed city archivist and then returned the material to city hall.

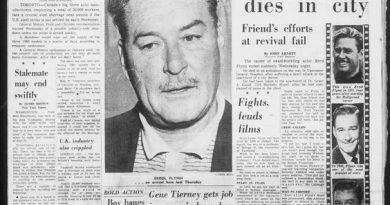

The city archives has evolved with donations from a number of families and organizations in the city along with Matthews’ own collection and transcriptions of interviews with native leaders and European settlers. As a result of his efforts, Vancouver became the first city in Canada to erect a municipal archives building, a striking structure half-submerged in the earth at Vanier Park. Appropriately, it was named in Major Matthews’ honor. He died in 1970 at the age of 92.

The archives is now part of the City Clerk’s Department. It houses original records of the city going back to 1886 as well as records and photographs donated by private individuals and organizations and prominent families. As a civic facility, it is open for public research on topics such as genealogy, architecture, neighborhoods and social issues.