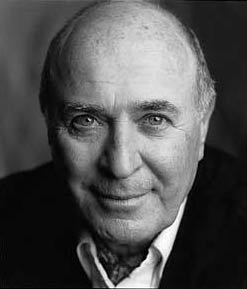

The Impresario

Ernie Fladell died in Lions Gate Hospital on Friday, Dec. 8, 2007, aged 81. Many Vancouverites have never heard of him, even when he was brightening their lives year after year. Not many others have done so much for this town’s performing arts—and for its residents—as Ernie achieved.

In retrospect, it was an unlikely achievement. He’d been born in Brooklyn in 1925, grown up in the Depression, and served in the U.S. Army in Europe at the bitter end of the Second World War. Returning to New York, he worked in a TV repair shop while taking night classes in writing, design and advertising.

His first job in advertising led to a sales-promotion job with NBC, and then to his own ad agency. In the late 1960s, he published a small bestseller, The Gap, written by himself and his nephew Richard Lorber about their attempts to understand each other. Life Magazine ran excerpts, with Ernie and Richard on the cover.

Prosperous, enjoying his job and family life, he might have stayed right where he was. Instead, in 1971, he sold his interest in the agency and moved his wife Judy and their teenagers, Matthew and Anne, across the continent to Vancouver. He opened a business in Lower Lonsdale, framing pictures and selling art posters.

The Fladells were part of a little-noticed aspect of the Americans who moved to Canada because of the Vietnam War. We think of American émigrés as young single men, draft dodgers or deserters. But in many cases, the whole family moved north to keep its sons out of the war. That was the Fladells’ motive.

Can do

My wife and I met Ernie and Judy when he and I were both writing for a small North Shore paper—I was doing book reviews and Ernie was writing funny, readable ads for his framing shop. We had a lot in common, and became good friends.

I jumped from being a technical writer in Berkeley to teaching college in Vancouver, and there I’ve stayed; Ernie went from advertising to a chain of remarkable jobs. The framing shop moved to Gastown, where Judy ran it and made friends with journalists Jack Wassermann and Jack Webster, whose offices were upstairs. Meanwhile, Ernie went to work in the new Social Planning Department at Vancouver City Hall. He was the city’s first cultural planner responsible for arts administration and development.

By now it was clear that Ernie had one remarkable talent: he could get things done, whether it was running an ad agency or moving to another country. He also had an ad man’s understanding of the people he was dealing with. At city hall, he got along well with mayors and councillors, and with his fellow bureaucrats. The grin, the bright blue eyes and the Brooklyn accent may have been part of his charm, but they really loved his ideas and his follow-through.

So he got the municipal government to buy and display artworks from Vancouver artists. He talked the city into celebrating its greatest resource at the first (and only) Vancouver Rain Festival, during which it predictably poured. He started Urban Reader, a magazine about city issues still fondly remembered by planners and community activists. That in turn led to a book, Vancouver’s First Century.

It wasn’t the last book Ernie inspired. In the mid-1970s, he supported Chuck Davis, a local writer and broadcaster, in the production of The Vancouver Book, published in 1976. This “urban almanac” was a treasure of information about the city, still valuable as a historical resource. Two decades later, Davis created an expanded version, The Greater Vancouver Book, and went on to create the Vancouver History website.

Making Vancouver a festival city

In 1976, Ernie also got the opportunity that would transform Vancouver into a festival city. The UN held its Habitat conference in Vancouver in 1976, and Ernie was in charge of organizing a performing-arts festival to go along with the event. It was not only a big success—it made a $40,000 surplus. Chuck Davis tells what happened next:

“Maurice Egan, the director of social planning, and his planner-cum-festival producer, Ernie Fladell, were urged by music critic Ian Docherty to replicate its success. Renamed the Heritage Festival and organized in co-operation with the VSO and CBC Radio, in June of 1977 the event again succeeded in attracting large audiences for music, drama and dance—and yet another surplus. Vancouver summer entertainment, which previously revolved around the PNE and Theatre Under the Stars, was never to be the same again.”

By now, Ernie could pitch his ideas to federal, provincial and municipal politicians, and the money flowed. In 1978, he launched not one but two festivals: the Vancouver International Children’s Festival in May, and the Vancouver Folk Festival in August. They didn’t just succeed financially; as Davis says, they changed the way we think about summer entertainment.

Without expecting to, the former ad man had become an impresario. For a time he stayed at city hall while also acting as executive producer of the Children’s Festival, now a yearly event. He travelled the world, looking for actors and dancers and musicians, and bringing them to Vancouver’s Vanier Park. The big red-and-white striped tents became a familiar sign of spring.

‘Might as well give them something good’

In the early 1980s, Ernie left city hall and moved to CBC as head of regional communications, while still running the festival. Then, in 1984, he became full-time executive director of the Children’s Festival, now a production of the Canadian Institute of the Arts for Young Audiences. Recruiting some highly capable administrators, Ernie ran the festival without commercial backing, using a simple premise: “Kids will watch anything, so you might as well give them something good to watch.”

He certainly did: the kids got to watch Sharon, Lois and Bram; Raffi; Korean dancers; and astounding British and Japanese theatre. Vancouver schools shipped their students to the festival by the busload, seizing the chance to show the kids what the performing arts could do.

Meanwhile, Ernie was also running simultaneous conferences for arts administrators and educators. I took part in a couple of them, and was amazed at the quality of the presentations and discussions.

Ernie and Judy’s home in West Vancouver was another kind of ongoing conference disguised as a party. On a summer afternoon, their poolside patio would be full of artists, journalists, publishers, broadcasters and educators—schmoozing, noshing, gossiping, joking, and having a wonderful time.

A worldwide success

In 1992, at 67, Ernie retired. But thereafter he was a fixture at both the Children’s Festival and the Folk Festival. By then it was clear that he had achieved a more than local success. The Children’s Festival had inspired almost 20 similar events, from Edmonton and Toronto to Virginia and Scotland. Dance troupes and singers would arrive in Vancouver and then move onto the festival circuit across the country and into the U.S. The best children’s performers in the world competed to be here.

Most of us, whether as parents or as kids (or both) have our memories of the Children’s Festival: lining up for face-painting, singing along with Charlotte Diamond, tromping on the duckboards on the occasional rainy day. My memories are of kites against the blue sky over English Bay, hanging out in the performers’ tent, and Ernie wandering from tent to tent, wearing a cap and a big grin.

He was the host of the biggest, happiest party in town, a party that’s been going on for 30 years. Always the ad man, he knew his audience; he knew what we wanted, and he gave it to us—music and dance and theatre, in a city made happier and more beautiful by them.

If you seek his monument, go to Vanier Park next spring, or Jericho next summer, and look around you.

(Crawford Kilian is a Capilano College teacher, a tireless blogger and the author of 20 books, including Writing for the Web.)

![Red Robinson [Photo: redrobinson.com]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/red_72_0040-390x205.jpg)