Charles Marega

Charles Marega was an Italian-born sculptor who arrived in Vancouver with his wife Bertha in 1909. He was about 38. The Maregas had planned to settle in California, but Bertha was so smitten by the North Shore mountains—they reminded her of her native Switzerland—that they changed their minds and stayed here. Marega taught art for 30 years in Vancouver, but he also left us a great deal of public art.

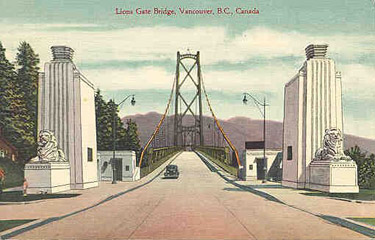

There are, most prominently, the two lions at the south approach to Lion’s Gate Bridge. There’s the David Oppenheimer bust across from the park board office in Stanley Park (Oppenheimer was Vancouver’s second mayor). There’s the statue of Capt. George Vancouver, commissioned to mark the city’s Golden Jubilee celebration in 1936, and installed on the north side of the brand-new city hall. There’s the deer crest and other decorations on Seaforth Armoury, the city coat of arms and the heads of Vancouver and Capt. Harry Burrard on Burrard Bridge, and a fountain in Alexandra Park, across from English Bay, to commemorate Joe Fortes, the lifeguard.

One of the more unusual of Marega’s outdoor pieces is the huge, old-fashioned, and yet impressive President Warren Harding memorial in Stanley Park. The story of how that commission arose is an interesting one: Harding had visited Vancouver in July of 1923, the first U.S. president to visit Canada, and wowed the locals. (They politely refrained from mentioning Teapot Dome, the nickname for an oil-lease scandal in which some of Harding’s senior aides, and at least one cabinet member, were involved, but in which the president is generally conceded to have been innocent—if over-trustful.) Seven days after leaving Vancouver, the president died of a heart attack in San Francisco. Vancouver was stunned, and the Kiwanis Club (Harding had been a Kiwanian) made a sudden decision to initiate an international competition for a suitable monument to the president, that monument to be placed in Stanley Park at the spot on which Harding had spoken to the citizens. The judges were well-known North American sculptors.

The winner of the competition: Charles Marega. (It was a happy coincidence that the sculptor was also a Kiwanian.) In 1926 the Harding memorial was unveiled. It created a sensation, and Marega was so pleased with its reception that he and his wife decided to become Canadian citizens.

The style of Marega’s work is passe now, and it’s unlikely anything like it would ever be let past the doors of, say, the Vancouver Art Gallery . . . and that’s an indication of how tastes have changed, because there was a time when Marega was considered it: In 1931 he was commissioned to execute a frieze (consisting of artists’ names in ornamental lettering) along the front of the city’s brand-new art gallery on West Georgia. He also designed medallions showing the profiles of six famous artists, these to be placed in the lobby of the gallery. In the redesigning of the building in the ’50s, Marega’s work was, apparently, discarded. (Actually, an anonymous collector rescued them and has them in his Fraser Valley home.)

Lions Gate Bridge

There’s plenty more of his work around, though. I haven’t mentioned, for example, the King Edward VII fountain on the west side of the courthouse. But’s it’s those lions at the Lion’s Gate Bridge that are seen most often by Vancouverites and visitors. By the time Marega got that commission in 1938, his life and career had begun a slow descent. His wife had died in 1936, and, says Marega enthusiast Peggy Imredy, “all his vitality left him then. He was devoted to her throughout his life. People who knew him only in the late ’30s have a different view of him. They see him as a shrunken and poverty-stricken artist.”

Remember, too, these were the years of the Great Depression.

Mrs. Imredy (whose late sculptor husband, Elek Imredy, is most well-known for his Girl in Wet Suit in Stanley Park) has a copy of a letter Marega wrote to relatives in Switzerland. It’s a sad little document.

“Thank God I have work now,” he writes. “I am modelling a lion for Vancouver’s suspension bridge. I had much trouble to get the work. The engineer is from Montreal and wanted the lion to be modelled in Montreal. But the president of the bridge committee, who is a long friend of mine, and his wife, who was a good friend of Mama’s, finally assigned the work to me. I would have preferred the lions to be in bronze or stone—but it has to be cheap, so they will be done in concrete, which annoys me, as I could have otherwise have made both lions from one model. However, I have to content myself to get work at all.”

The lions were placed at the bridge in January, 1939. Two months later, at the age of 67, Charles Marega collapsed and died of a heart attack. He had just finished teaching a class at the Vancouver School of Art, and was reaching for his hat and coat when he fell heavily to the floor. It was March 24, 1939.

His obituary in The Province said he was “acknowledged to be the greatest sculptor in Western Canada.”

“His moulds and models were offered to the Vancouver Art Gallery after his death,” Peggy Imredy says, “but were refused. Everything was scattered. Some small pieces of sculpture have surfaced in second-hand shops; they’re here and there in Vancouver. Mr. & Mrs. Marega’s ashes have disappeared. There is no grave for them. He had $8 in his bank account.”

![Captain George Vancouver Monument [Image: Vancouver Heritage Foundation]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cpt.-George-Vancouver-Bust-Madeleine-6-1024x681-1-800x445.jpg)

![The Empress, Victoria [Image: Wikipedia]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Fairmont_Empress_Victoria_British_Columbia_Canada_08-390x205.jpg)