Charlie Crane

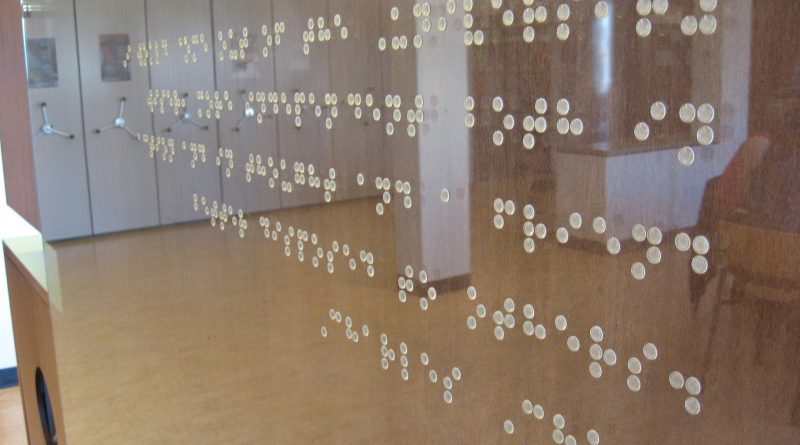

One of the most remarkable people in Vancouver history, Charles Allen Crane, who died in 1965, was both blind and deaf. He couldn’t see anything, he couldn’t hear anything. Yet he attended UBC for two years, worked as a reporter for the Ubyssey, wrote for the Province, became a star varsity wrestler and worked as a “translator” for blind students, converting books into Braille. He read thousands of books. Those 6,000 Braille books were Charlie’s, left by him to the university. It was Canada’s largest Braille collection.

Today, the Crane Library is the Crane Resource Centre and Library, the principal resource for UBC students and other people who are blind, visually impaired or print-handicapped. There’s an eight-studio book recording and duplicating facility there, computers that convert print to synthesized speech, computer work stations with voice synthesis and image-enlarging, a computerized Braille transcription facility, a talking on-line public catalogue, closed circuit TV magnifiers, and more. And it all started with Charlie Crane.

Charlie was born in Toronto in 1906. At the age of nine months he was hit by an attack of spinal meningitis. His mother was told he would likely die, but she nursed him night and day and pulled him through. But the meningitis had destroyed the baby’s sight and hearing.

Charlie told an interviewer once, “I was admitted to the school for the blind in Halifax in 1916 when I was 10 years old. Of course, I knew nothing of language then but my teachers told me that in six months I could pronounce 2,000 words to their satisfaction.”

How had he done it?

“The first word I was taught to pronounce was ‘come,’” he explained. “Miss Conrod, my teacher at the time, pronounced the word very deliberately whilst I held the fingers of one hand on her throat and of the other hand on her lips. When, after repeated trials, I pronounced the word ‘come’ in a clear, subdued voice, altogether to the satisfaction of Miss Conrod, she instructed me to knock at the door and say, ‘Come.’ This I did. The door, which was ajar, was thrown open and three teachers came forward, and one of them said in the dumb language, ‘You asked us to come, so we have come to you.’ I knew then for all time what the word ‘come’ meant when it was spoken.”

That “dumb” language consisted of spelling out with your fingers every word, letter by letter, on Charlie’s hands.

The boy developed another skill that people who knew him spoke of with awe. S.G. Lawrence, principal of the School for the Blind in Vancouver, in 1926 told an interviewer a story about his star pupil. (Charlie and his family had moved to Vancouver in 1921.) “Charlie’s sense of touch is nothing short of marvellous,” Lawrence said. “Not one of our pupils has even approached him in this respect. I will give you an example. Some years ago Dr. Carmichael preached in Vancouver. Charlie’s father and I took Charlie along. After the sermon Dr. Carmichael shook hands with Charlie. Charlie put his hand on the doctor’s head and shoulder for a moment. The doctor talked to him on his fingers.

“Five years passed by and, unknown to Charlie, who had not met him in the interval, Dr. Carmichael again visited Vancouver. He called at the school, and seeing Charlie walked over and shook hands. Charlie held the doctor’s hand gripped in his own for fully a minute and then exclaimed, ‘Why, it’s Dr. Carmichael’.”

People naturally thought of Helen Keller when they met or heard about Charlie Crane. “But,” says Paul Thiele, “there was one major difference between them: Charlie had a sense of humor.”

Paul Thiele, now retired, was the head of the Crane Library in the 1980s. Paul had met Charlie in the early 1960s. “I was about 18,” Paul says, “working as a recreation director at C-NIB Lodge on Bowen Island, run by the Canadian National Institute for the Blind.”

Paul, by the way, is legally blind himself, with about 10 per cent vision.

“Anyway, I heard Charlie Crane was coming to be a guest at the lodge. He was in his mid-50s at the time. The staff there talked about this guy with real awe. Well, I met him and I felt somewhat disappointed. To me, he had all the earmarks of being retarded.” He gestures. “I sort of wrote him off.”

The young recreation director has a surprise coming.

“I took a bunch of holidayers out for a nature walk—these were blind adults—and Charlie wanted to come along. One of the things I did was to get the people to come up to a big tree along the path and put their arms around it . . . so they could sense the size and the feel of the thing. Well, Charlie came up, too, and put his arms around the tree. And then he asked me through an ‘interpreter’ who understood his speech, what kind of tree it was.”

Paul laughs. “Hell, I don’t know trees. So I faked it. I said, uhh, maple.”

The interpreter spelled that out on Charlie Crane’s hands.

Later that afternoon, back at the lodge, Paul was handed a note from Charlie Crane. In the note, Charlie thanked Thiele for his interesting nature walk and said he had found it very informative. He wanted to bring up one small point about that tree he had put his arms around.

“It was not, in fact,” Charlie wrote, “a maple, or acer macrophyllum. I was able to deduce, by the moss on the tree, the indentations of the bark, and the shape and moisture content of the leaves that it was, in fact, a mature Alnus Rubra, or red alder.”

“Now,” says Paul, “I don’t really remember the exact tree he named because I don’t have the letter any more, but I do remember holding that letter in my hand and looking at it . . .” There’s much more to tell you about Charlie Crane, and it will be in my book.