Errol Flynn

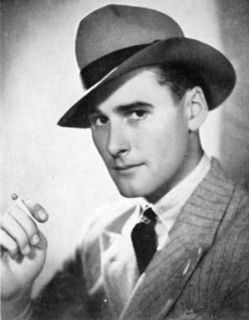

What an astonishing life he led. We can be absolutely sure of just a handful of facts. He was born in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia on June 20, 1909 and died in Vancouver October 14, 1959. He claimed to have been, in his life before film, a police constable, sanitation engineer, treasure hunter, sheep castrator, shipmaster for hire, fisherman and soldier. At age 24 he got into movies, acted in 61 of them, and became a superstar in his seventh, the 1935 swashbuckler Captain Blood, a role he got when the original star, Robert Donat, was laid low by asthma.

Until the late ’40s he stayed a big box office attraction, in movies like Charge of the Light Brigade; Adventures of Robin Hood; Dawn Patrol; Dodge City; Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex; The Sea Hawk; They Died With Their Boots On; Objective, Burma! and a dozen others. He was good at it, too. But then his life style off-screen began to take over. “Always known as a heavy drinker and smoker,” says movie historian Ephraim Katz, “he was now beginning to experiment with drugs.” His movie face began to lose its fabled handsomeness.

Flynn was married three times, had countless liaisons, was accused of statutory rape, but cleared. There seemed always to be a woman on his arm. His success with women was, literally, legendary.

Flynn’s reputation took a severe battering with the 1980 publication, long after his death, of a book by Charles Higham that claimed, among other things, that Flynn had been a Nazi spy, that he had conspired to assist in the assassination of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) during their 1939 tour of Canada, that he was homosexual . . . and on and on. That book and a later, equally scurrilous, one by David Bret painted a portrait of a man who was infamy incarnate. Did he really serve guests omelettes to which he added (in the words of General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove) his “precious bodily fluids”

We’ll never know. Both books have been shown to be riddled with inaccuracies, with truth and fantasy blended into an indiscriminate mess. (The Nazi connection seems to have been entirely concocted.) Part of the reason was Flynn’s own personality. He said it himself once: “You wonder, who’s the you? And who’s the chap on the screen? I catch myself acting out my life like a goddamn script.”

Flynn, understandably, was continually plagued with money problems. He picked up the phone in New York one fall day in 1959 and called an old friend, stock promoter George Caldough, in Vancouver. It happens that at the time Flynn called Caldough was in a financial bind himself. As he later wrote in Weekend Magazine—a long, cheerful piece he wrote in prison—he was desperate “for some new vision to bail me out and put my company on an equitable footing—but what?”

Flynn’s call gave him the answer. The actor wanted to know if Caldough was still interested in buying his yacht, the Zaca. (Caldough had admired the boat extravagantly.) He was, and arranged to meet Flynn in Hollywood the following week. Caldough had recently read about an American company that intended, through public subscription of $1.9 million, to finance a deep-sea treasure-hunting expedition off the coast of Spain. Caldough, his brain churning, began thinking about the Zaca, with ERROL FLYNN at the helm, searching for sunken Spanish gold. That would raise one hell of a public subscription.

In a fever of excitement and speculation Caldough flew to Hollywood and met Flynn.

He was shocked by the actor’s appearance. “We hadn’t met in two years, but he had aged 20 . . . He followed me to Vancouver—accompanied by his 17-year-old friend, Beverly Aadland—after about 10 days. If anything, his appearance had deteriorated and he seemed to need help in just getting around. But his personal charm was unabated . . .”

Flynn, who revelled to some extent in his notoriety, told reporters on his arrival in Vancouver that he hoped to star in a film to be made of the Nabokov novel Lolita, with Aadland to star as the “nymphet.” (Incidentally, according to the birthdate for Beverly Aadland shown in the Internet Movie Database—September 17, 1943—she would have been just 16, not 17, when she arrived here with Flynn. Aadland was certainly precocious. She once told an interviewer that at age 12 her measurements were 34-28-34.) Flynn was still married to actress Patrice Wymore at the time.

Flynn and Aadland stayed with the Caldough family on Eyremount in British Properties for several days during that October 1959 visit. “He seemed to be happiest when reminiscing, watching TV or talking to my children,” Caldough wrote. Even though his glory days were done, Flynn’s visit excited Vancouver mightily. He was, in turn, delighted when Orpheum Theatre manager Ivan Ackery went to great lengths to obtain and show a short film Flynn had made about the Zaca in 1952, and phoned Ackery to thank him.

Flynn was supposed to go to New York for a TV show, but his famed disregard for time was in full flower. The Caldoughs half-heartedly tried for three days to get him on the flight to New York, but they kept missing it. There was always another party, more people to entertain, more Hollywood stories to tell.

Finally—it was October 14, 1959—Flynn said he really did have to go and suggested they leave for the airport three hours early.

En route, Flynn began to experience severe pain in his back and legs. Caldough, who was driving, veered off and headed for the West End penthouse apartment—at 1310 Burnaby Street—of a friend, Dr. Grant Gould. Astonishingly, not long after their arrival, a few people materialized and another party began!

Flynn, who was standing against a wall to relieve the pain in his back, regaled the group with stories of the Hollywood figures he had known, especially John Barrymore and W.C. Fields (both, tellingly, heavy drinkers). He was, apparently, a superb story teller. But then he stopped and announced he was going to lie down for an hour and then would take everyone out for dinner. He moved into the doctor’s bedroom and lay down on the floor.

When Beverly Aadland looked in on him a little later to see how he was, she found him trembling, his face blue. She could hardly hear his heart. Her screams brought the doctor . . . but it was already too late.

Al Gowan, a member of the inhalator squad (summoned by one of the guests, Art Cameron, who was manager of the Sylvia Hotel at the time), said “Flynn was dead before we got there. The man was a living skeleton. His liver was gone, his heart was gone.”

The death certificate, dated October 23, indicated myocardial infarction, coronary thrombosis, coronary atherosclerosis, liver degeneration, liver sclerosis and diverticulosis of the colon as the causes of death.

Flynn’s autobiography came out that same year. It was titled My Wicked, Wicked Ways. They caught up with him in Vancouver. He was 50.

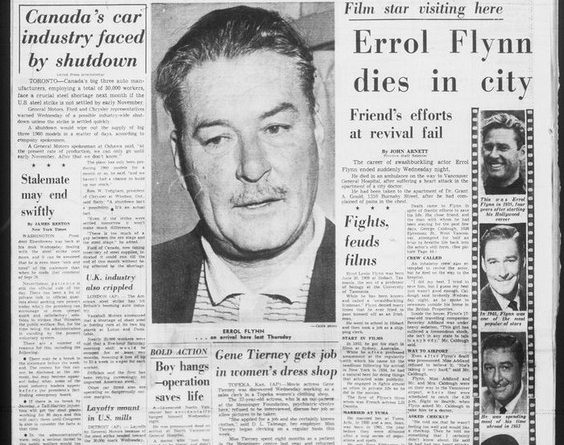

Top Image: Front page of the Province when Errol Flynn died in the West End. PROVINCE/VANCOUVER SUN