Lauchlan Hamilton

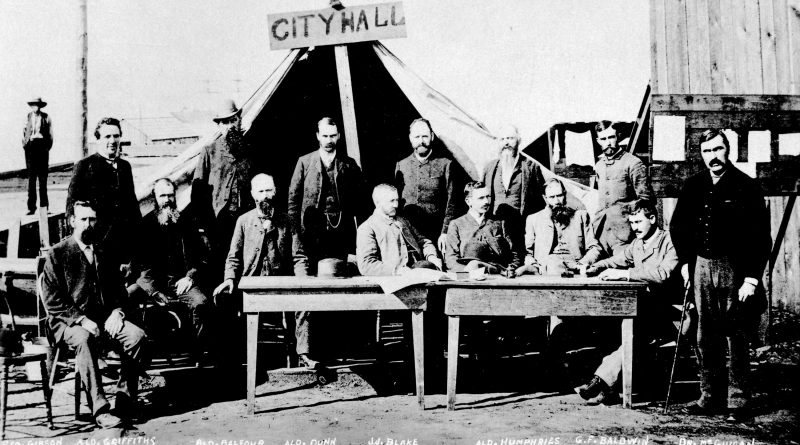

Lauchlan Hamilton was one of our first aldermen. That’s him in the dark jacket third from the right of the sitting men. [Photo: VPL #508]

Lauchlan Hamilton was the CPR land commissioner who, starting in 1885 as a young man of 33, surveyed much of Vancouver and named many of its streets. (A plaque commemorating his work is on the building at the southwest corner of Hamilton and Hastings, once a bank.)

If you live or work downtown Hamilton put you where you are.

![Cambie and Hastings Streets

[Photo: http://en.wikipedia.org]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Vic_square_wires.jpg)

[Photo: http://en.wikipedia.org]

Speaking of street names, if Hamilton had had his way, Arbutus would be two blocks west of Cambie, between Alder and Ash. More on that later.

It’s one thing to read accounts of the activities of people like Lauchlan Hamilton. It’s quite another to read their own words. In the Vancouver Archives is a hand-written letter, dated Oct. 4, 1929, carefully inscribed by Hamilton (77 at the time) during a brief visit to the city. The letter’s addressed to J. Alex Walker of the town planning commission. It was written more than 40 years after his survey and reading it, it suddenly dawned on me: this is the man who designed downtown Vancouver. I’m actually holding his letter—nearly 80 years after he wrote it—and reading what he thought of that job.

“I cannot say that I am proud of the original planning of Vancouver,” Hamilton writes, after explaining that the shortness of his visit precludes a personal meeting with Walker. “The work, however, was beset with many difficulties. The dense forest, the inlets on the north and False Creek on the south, the pinching in of the land at Carrall Street . . .” and so on, and so on.

If you look at a map of Vancouver, you’ll note that east-west streets such as Hastings and Pender turn at an angle as they pass Cambie and enter the downtown peninsula. Presumably Hamilton didn’t want to have the streets make that bend because, in his letter to Walker, he complains of a severe problem: His “original plan” for the direction of the streets in the city’s downtown peninsula had to be altered. It seems a property owner named Pratt refused to go along with Hamilton’s design.

Hamilton doesn’t elaborate, but I asked John Atkin to. John writes: “Pratt was one of the large land owners in the West End who refused to allow Hamilton to replot the area, hence almost all of the streets going east west across Burrard don’t match up. Hamilton was quite mad about this. The West End streets were drawn up on a plan and registered in the 1870s but were never surveyed on the ground and Hamilton had to fit his work to the registered plan which is why the lot sizes in that area are so odd. For the downtown he had to set the streets along the already established boundary of the West End, which was Burrard Street, and for the streets to the east they had to relate to the already established Hastings Townsite boundary at what became Nanaimo St. So you had three different street grids meeting on the peninsula.”

Hamilton’s reference to dense forest was no exaggeration. The trees were plentiful and they were big: One astonishing specimen (called the Russell tree after Aleck Russell, the man who cut it down during the clearing of the streets) stood on what was to become Georgia between Seymour and Granville, and was measured after its fall at 95 metres (310 feet), about the height of the Marine Building.

The Archives also has a collection of field survey books used by Hamilton and those working for him. It’s fascinating to leaf through those brittle, yellowing pages and see the pencilled notes and drawings made more than 120 years ago as the surveyors decide to cut a “Granville Street” through here and a “Nelson Street” through there. The pages are covered with scribbled computations and little memos, each street plan carefully dated: The corner of Cambie and Hastings, for example, future site of Victory Square, was laid out on April 30, 1886. The survey of Granville south of Nelson began March 15, 1885. (If you’re a surveyor and you haven’t seen these little books, by all means visit the Archives and ask to have a look.)

“I had a free hand,” Hamilton wrote in 1936 to archivist Major J.S. Matthews, “in the property lying south of False Creek [This was a reminder of difficulties he had north of that area] so there I was able to adopt the modern style of naming the avenues, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc., and the streets I called after trees, such as Alder Street, Birch Street, Cedar Street, etc., preserving them, as much as possible, according to the arrangement of the alphabet . . .”

Hamilton got the idea of using tree names when he saw a hand-made map of the area in which a resident Scot had pencilled in the notation ‘Heather.’ (That Scot had probably seen some growing in that area.) Heather was the first of the ‘tree streets’ to be named.

Unfortunately for people with faulty memories Hamilton’s intention to have those streets in alphabetical order was not carried out because the instructions were garbled and the draftsman wrote them down in the order we know them today (moving from east to west, Heather, Willow, Laurel, Oak, etc.)

Hamilton mentioned Cedar Street. Where’s that? When the Burrard Bridge went in in 1932, it connected to Cedar Street south of the bridge—the name Burrard was extended and Cedar disappeared. (The same thing happened with Centre Street, once between Hemlock and Fir—it disappeared when the first Granville Street Bridge crossed False Creek and became an extension of that street.)

![Constance Bodington Hamilton

[Photo: VA Port P290]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/constance_hamilton.jpg)

[Photo: VA Port P290]

Hamilton’s impact on early Vancouver’s physical appearance was enormous, but this is just one of the Western Canadian cities he laid out. William Van Horne and the CPR gave him complete authority (at the age of 28) to select the 25 million acres the railway had been given as a subsidy and also authorized him to survey the land for the cities along the line. Hamilton designed early Calgary, Regina and Moose Jaw and, he once wrote, “numberless” other settlements along the line.

(One treasure the Archives has is a letter, written by Hamilton to his mother in 1872 just after his 20th birthday. He was working on the British North American Boundary Commission, which was surveying the 49th parallel—they were at Pembina, Manitoba at the time—and he tells, among other things, of seeing the 50-tent American surveying party across the river. The letter is written by a strong young man enjoying life, having a simple faith in God and proud of his work.)

Hamilton was in Vancouver for fewer than five years. In 1888, at about age 36, he was recalled to Winnipeg to become the CPR’s senior land commissioner.

He had more than 50 active years of life left to him, dying in Toronto in 1941 at the age of 88, survived by Constance, whom he had married in Vancouver in 1888.

![Fairview Baptist Church in Vancouver [Image: FairView Baptish Church]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/10247407_669782893067748_6617630364129196857_n-390x205.jpg)

![Crofton House ca. 1911 [Image: evelazarus.com]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Alvo-Crofton-House-390x205.png)