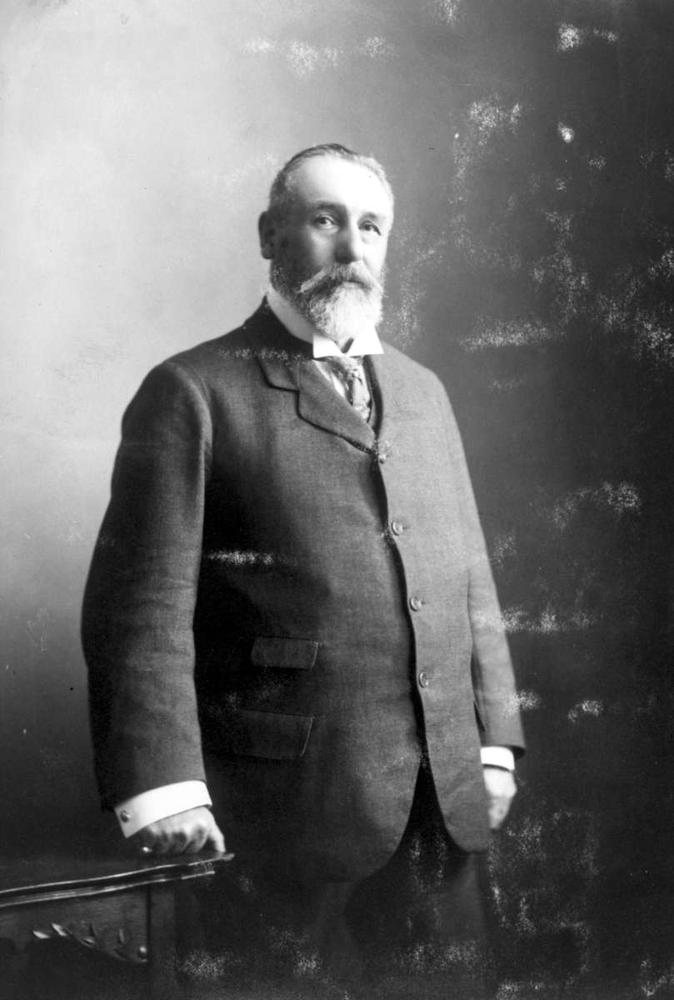

Malcolm Alexander MacLean

His name was Malcolm Alexander MacLean, so it’s no surprise to learn that Vancouver’s first mayor spoke Gaelic like a Highlander. He was born in Tyree, Argyllshire on Scotland’s west coast, in 1844. He arrived in Granville in January of 1886, three months before it became Vancouver.

MacLean had done a lot in his 42 years before arriving here: three years of teaching in Ontario, office work for the Cunard Steamship Company in New York, running a finance management company in the same city, then into Canada to set up his own wholesale trade in Winnipeg just before the CPR arrived.

When the railway did get to Winnipeg, MacLean’s company flourished and kept on flourishing for a decade. He bought property, and when a depression hit the West, he kept that property. That proved to be a good decision.

MacLean took his family to their summer home in the Qu’Appelle Valley in Saskatchewan to ride out the depression, and landed smack in the middle of the Riel Rebellion of 1885.

It was time to move on again.

An old friend from Scotland wrote MacLean from Honolulu: he was establishing a sugar beet factory there. Did MacLean want to move to Hawaii and become a partner? MacLean thought he did, but when he and his family got to San Francisco, whence the boat to Honolulu would sail, something told him not to go. Canada was his home, he said later. He couldn’t turn his back on her.

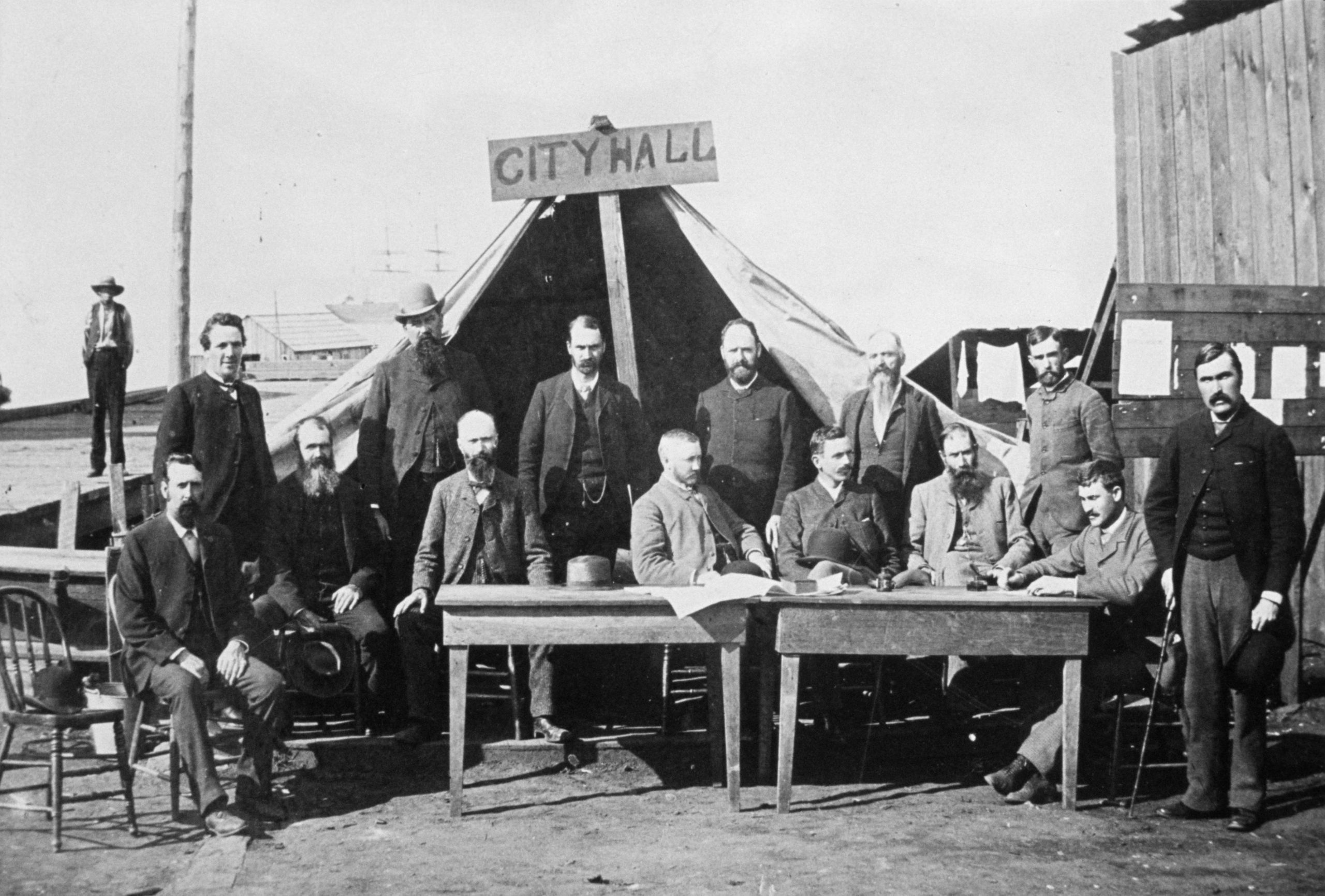

So the family turned north and came to Granville instead. When they arrived the population of the place was about 600 and, says Derek Pethick in Vancouver Recalled, there were “but a hundred habitable buildings.” By May there were six times as many. One source says there were a thousand by June.

But they were mostly a humble lot of structures. A glance at any photograph of the time tells the story: clumps of buildings scattered pell-mell around the landscape, leaning precariously between the massive chopped-off stumps of once-lofty trees, struggling to emerge from a wild tangle of weeds, shrubs, creeks and fallen timber.

A dedicated man could make a fast impression in a town like this, and three months after his arrival Malcolm MacLean was in the race to be the first mayor of the brand new city, incorporated April 6, 1886. (He was also one of the earliest organizers of the St. Andrew’s and Caledonian Society—still active in Vancouver—and served as its first president.)

BC Archives

MacLean’s opponent, a one-time longshoreman named Richard Alexander, was manager of the Hastings Sawmill and had lived in Granville/Vancouver for 12 years.

The election May 3 was as honest as could be expected for the time, which is to say not at all. MacLean won by 242 votes to 225, and successfully fought back a legal challenge by some of his opponent’s supporters. (At one point, Alexander led a large contingent of his Chinese workers to vote, but they were forced back by a larger contingent of white workers. Besides, Chinese weren’t allowed to vote, anyway.)

On his first day in office, during opening remarks to the new council, MacLean sounded an alarm which in a few weeks would come to fruition. “We require immediately protection from fire,” he told the other council members, “and any delay on this matter endangers a large amount of valuable property. A communication will be laid before you today in regard to a fire engine which, if you have time, had better be discussed at this meeting.”

They discussed that fire engine. They even bought it, from the Ronald company in eastern Canada. But by June 13, the day the city burned down, the engine hadn’t arrived and the Volunteer Hose Company No. 1 had only axes, shovels and buckets. It wasn’t enough. MacLean was wiped out by the fire, but his Manitoba land holdings kept him going. In fact, in early 1891 they began to appreciate rapidly, and he soon was prosperous again.

After serving two one-year terms, declining to be paid, MacLean retired as mayor.

Early in 1895 he was appointed stipendiary magistrate for Vancouver district, but his health was failing and he never served. He died April 4, aged 51.

Wife Margaret Anne MacLean made her mark, too. In 1909 she founded the Women’s Canadian Club in Vancouver, and was the first president of the Women’s Pioneer Society. She lived on to 1934, dying at 87, survived by a son and two daughters.

![Sun Yat-Sen Garden [Image: The Canadian Enclyclopedia]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/dd1cb474-9295-42a9-b726-f7d870214d33-390x205.jpg)

![Chaplin in "A Night in an English Club," 23 June 1912 [Image: Kansas City, MO, via TheRoyalZanettos.com]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chaplin-One-Night-1912-390x205.jpg)