Rattenbury

If you live in British Columbia you’ve been looking at the work of Francis Mawson Rattenbury all your life. He was an architect, a supremely confident man in his youth, a hugely successful man in his middle life but, finally, a pathetic victim of a famous crime.

Rattenbury, called ‘Ratz’ by his friends, was born in Leeds, England in 1867. He is well known for his creation of the provincial legislative buildings and the Empress Hotel, both in Victoria. He did work in Vancouver, too, including a wing of the now-vanished first Hotel Vancouver and, of course, the 1910 provincial courthouse—now home to the Vancouver Art Gallery.

At age 18 Rattenbury began work with a prominent architectural firm in Bradford, near Leeds. It was a sleepy little company, and the tall young redhead was anxious to move on. In 1892 he decided to come to Vancouver.

![BC Legislature

[Photo: flickr.com]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/legislature.jpg)

[Photo: flickr.com]

His timing was terrifically lucky—in the July 5, 1892 issue of the World was a Notice To Architects announcing a competition to design the new legislative buildings in Victoria.

Rattenbury shamelessly exaggerated his experience, which was modest, but came up with a design that astonished and pleased the judges with its splendor. (In his terrific book on early BC architects, Building the West, architectural historian Donald Luxton says Rattenbury’s design “has come to be recognized as British Columbia’s finest example of architecture.”)

There was more to come: drawings had to be submitted under a nom de plume. Rattenbury, who was nobody’s fool, signed his drawings “B.C. Architect.” That may have cinched it for him. He won easily over more than 60 other architects and he did it singlehanded. It was March, 1893. He was 25.

That and later successes fed a great deal of bitterness from rival architects toward Rattenbury.

For a detailed look at Ratz’s career, read the late Terry Reksten’s excellent 1978 biography, Rattenbury. (Further editions in 1998 and 2005.)

The decline in Rattenbury’s fortunes is all the more poignant when one considers the heights he had once reached. In June, 1898 he had married Florence Nunn of Victoria, but by 1923 the marriage was a shambles. They lived in the same house, but no longer spoke to one another, “depending,” wrote Reksten, “on their daughter Mary to carry messages between them.”

Then, at a reception in the Empress, Ratz met a young woman named Alma Pakenham. She was everything Florrie Rattenbury was not. “She had a lovely oval face,” Reksten writes, “deep hauntingly sad eyes and full lips which easily settled into a pout, at once fashionable and sensuous.” She was also adventurous and fun-loving.

And she would be the cause of Francis Rattenbury’s murder.

The two of them began an affair that shocked the Victoria uppercrust among whom Rattenbury moved. Alma, whose first husband had been killed in action in the First World War, had remarried—and that made the scandal even more thrillingly offensive. Ratz moved Alma into his house, living with her on the second floor while Florrie lived upstairs.

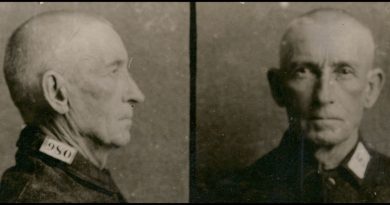

![Francis Mawson Rattenbury, Municipality of Oak Bay Photo

[Photo: freemasonry.bcy.ca]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/rattenbury_f.jpg)

[Photo: freemasonry.bcy.ca]

The Rattenburys divorced in 1925 and Ratz and Alma (herself freshly divorced for a second time) married. But the hostility of Victoria society, and a drying up of commissions, drove the erring couple from the city. They left for Bournemouth, England, taking with them a son, John, born in December 1928.

The new marriage didn’t work out. By 1934 Rattenbury, then aged 67, and with no new work coming in, had sunk into a desperate depression, had begun drinking heavily, was impotent and talked almost daily about killing himself.

In September of 1934 Alma, then 39, took a lover. He was a simple-minded 17-year-old named George Stoner, who worked for the family as a chauffeur and who, as it turned out, had a violent streak.

One day in November 1934 George Stoner—influenced, he said, by opium (although that’s disputed) and imagining that Alma was cooling in her ardor for him—took a mallet he had brought from his grandmother’s home and smashed it down a number of times on Rattenbury’s head. Rattenbury died in hospital soon after.

Writer James Agate covered the May-June 1935 trial. Here’s a portion of his account:

“Wednesday, 29 May. The Daily Express asked me to do an impression of the Rattenbury Trial at the Old Bailey. The facts were very simple and hardly disputed. Mrs Rattenbury, aged thirty-eight, wife of an architect aged sixty-seven, had been the mistress of her eighteen-year-old chauffeur named Stoner. Somebody had hit the husband over the head with a mallet, both of them having at one time or another taken the blame on themselves.

“It was all very like the three French major novelists. The way in which the woman debauched the boy so that he slept with her every night with her six-year-old son in the room, and the husband who had his own bedroom remaining cynically indifferent—all this was pure Balzac. In the box Mrs Rattenbury looked and talked exactly as I have always imagined Emma Bovary looked and talked. Pure Flaubert. And last there was that part of her evidence in which she described how, trying to bring her husband round, she first accidentally trod on his false teeth and then tried to put them back into his mouth so that he could speak to her. This was pure Zola. The sordidness of the whole thing was relieved by one thing and one thing only. This was when Counsel asked Mrs Rattenbury what her first thought had been when her lover got into bed that night and told her what he had done. She replied, ‘My first thought was to protect him.’ This is the kind of thing which Balzac would have called sublime, and it is odd that, so far as I saw, not a single newspaper reported it . . .”

Stoner was convicted of the crime and sentenced to hang. Alma was found not guilty, but committed suicide a few days after her release, stabbing herself in the heart. Public sentiment led to the commuting of Stoner’s death sentence, and he was instead sentenced to life imprisonment. He was released seven years later.

The murder caused a sensation, the trial is still studied, and the events inspired playwright Terence Rattigan to write the drama (1977) Cause Célèbre. (At one of the performances, someone recognized George Stoner in the audience. He would have been 61 at the time.)

Rattenbury is buried in the Wimbourne Road Cemetery in Bournemouth. “To foil the curiosity-seekers who are attracted by the continuing interest in his murder,” Terry Reksten wrote, “his grave remains unmarked.”

![The Empress, Victoria [Image: Wikipedia]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Fairmont_Empress_Victoria_British_Columbia_Canada_08-800x445.jpg)

![Red Robinson [Photo: redrobinson.com]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/red_72_0040-390x205.jpg)