The Life and Times of Foon Sien

Largely forgotten since his death in 1971, Wong Foon Sien was perhaps the most influential person in Vancouver’s Chinatown, if not in Canada, in the easing of restrictions of the immigration laws. In the late 1940s, the Chinese in Canada were allowed to bring in from China their spouses, unmarried children under 21, father over 65 years of age and mother over 60. It took Foon Sien eleven years of annual visits to Ottawa to ease the restrictions. The effect of the changes impacted the ‘bachelor society’ of Chinatown by correcting the imbalanced ratio of Chinese men to Chinese women.

![Foon Sien

[Photo: Larry Wong]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Foon_Sien.jpg)

[Photo: Larry Wong]

His year of birth is uncertain. One account has 1899, others have either 1901 or 1902. His Chinese name was Wong Mun Poo and he was born in China. The birth date is July 7, which he assured the writer in a 1960 interview.

His parents migrated to Cumberland, B.C. where his father became a successful merchant and ran a general/herbal store. As a 10-year old, Foon studied the Four Books and the Five Canons of Chinese learning after public school—his parents envisioned him having a career in Imperial China. Like most Chinese parents of the time, they wanted to send Foon Sien to China for a proper education. Their plans went awry when a young Chinese revolutionary named Dr. Sun Yat-Sen visited Cumberland in 1911 on a fund-raising mission to overthrow the Qing Dynasty. It made an impression on the young Foon Sien, who was inspired to study law. When he finished high school he moved to Vancouver.

He was one of the first five Chinese to attend the University of British Columbia, but remained for just one year. His first job came from BC’s attorney general A.M. Manson as an official court interpreter for the province of British Columbia. One of his early cases was the trial in 1924 of Wong Foon Sing, the houseboy accused of killing nursemaid Janet Smith. [Editor’s note: see the 1924 page on this site’s chronology for more on that fascinating case.]

Chinese born in Canada were considered British subjects but not citizens of Canada. They held the status of Aliens and were listed as such on the electoral lists as far back as 1867. In 1874, the B.C. government proclaimed, “Chinamen of the Province of British Columbia may not make application to have their names inserted in any list of voters and are disqualified from voting at any elections.”

The Chinese government in the early part of the twentieth century deemed all Chinese born outside of the mother country to be Chinese Nationals. If a Chinese born in Canada wished to become a Canadian, he would have to write for permission from the Chinese government and, once granted that permission, apply to the local courts for citizenship which, in most cases, was turned down.

Chinese trained in the professions such as law, pharmacy, and accounting in universities could not join the professional societies as their first requirement for membership was Canadian citizenship.

In 1923 the federal government introduced the Immigration Act, commonly known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. The intent of the legislation was to keep Chinese out of the country. In spite of the head tax imposed on Chinese immigration since the completion of the CP Railway, starting at a fee of $50 and rising to a maximum of $500 in 1903, Chinese immigrants continued entering Canada.

The 1923 Immigration Act was the only act in Canadian parliamentary history specifically aimed at a particular race. The legislation shut the door to any further Chinese migration with the exception of students, ministers, diplomats and Chinese born in Canada. The effect of the Act was disastrous on the Chinese communities. With no emigrants coming in, the present population of men were isolated from their families in China, away from their wives and children. Then the Great Depression began, and the situation became particularly desperate for Canada’s Chinese. Some left Canada for China, some lost their jobs and homes, some accepted their fate to wither in Chinatown, and some committed suicide. The population of the Chinese community became overwhelming male, a ‘bachelor’s society’.

Foon Sien became prominent in 1937 when he was appointed publicity agent for the Chinese Benevolent Association’s aid-to-China program. He was successful in stopping the export of scrap metals to Japan during the Second World War and became known as “Japan’s No. 1 enemy in North America.” He was also the founder of several associations, the most important being the Chinese Trade Workers’ Association in 1942.

During the war, he was recruited into a Canadian government department called the National War Service to look after mail and telegrams in the Chinese and English sections of the censorship unit.

In 1945, after the war, Foon went to Victoria to join the editorial staff of the New Republic Chinese Daily. He campaigned for franchise rights denied to the Chinese in Canada. Along with other Chinese leaders and veterans, they succeeded and the 1923 Exclusion Act was repealed on May 14, 1947. This in turn led to the rights to citizenship and the vote. He was recognized for his efforts with an award from the Chinese Canadian Citizens Association.

In a peculiar way, Canada was a nation without citizens before 1947. “Canadians” were simply British subjects living in Canada. For a country that emerged from the Second World War with a strong sense of nationhood, it was embarrassing. Not until a Liberal cabinet minister toured the military cemetery at Dieppe, the site where Canadians fought and died in defence of their country, was the Canadian Citizenship Act created. On January 1, 1947 the Canadian Citizenship Act came into effect and Canadians finally became “Canadian citizens.” That minister was Paul Martin, Sr., father of the former prime minister.

Even so, Canadian immigration policy was highly restrictive and admitted few immigrants and it was this very issue that Foon Sien took as his cause. In 1948 he became the president of the Chinese Benevolent Association and for the next eleven years lobbied the federal government in Ottawa for relaxation of the qualifications of Chinese families.

In an article in the June 3, 1955 issue of Chinatown News Foon Sien wrote that “. . . our people are still suffering reverses in our fight for equal immigration rights. In 1951 I pleaded with Mr. Harris, then the Minister of Immigration, to allow entry for unmarried children of Chinese Canadians between the ages of 21 and 25 on compassionate grounds. This was allowed at the time but was stopped by a new ruling dated March 12, 1955. These reverses in our struggle have handicapped us seriously in our struggle for equal immigration rights.”

He continued: “It would be a great boon to aging Chinese Canadians if they could bring youngsters to Canada to give them the advantages of the better standard of living and way of life here. Not only would this make up in part for the sacrifice these men have made in being separated from their families so long, but it would provide Canada with a fine new type of Chinese citizens who would rapidly assimilate the culture and traditions of this country.”

In 1957 Foon was instrumental in changing the imbalance of Chinese men to women by convincing the government to adopt a policy that would allow Chinese men living in Canada for two years to post a $1,000 cash bond for their fiancées from China.

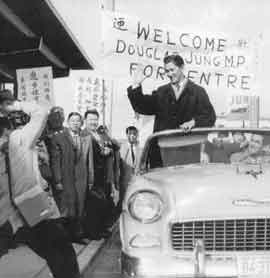

In the course of his life Foon became a staunch supporter of the Liberal Party with one exception: that was when Douglas Jung, a young war veteran and lawyer, ran for the Conservative Party in Vancouver Centre and won by a landslide to become the first Chinese Canadian Member of Parliament. The year was 1957.

Regardless of what political party was in power Foon Sien continued his annual trek to Ottawa. During this time, there were newspaper accounts of illegal Chinese immigrants coming into the country. The accusation was denied by the Chinese but on a Sunday morning in May of 1960 there was a rude awakening, a shock to Chinese communities all across Canada.

The RCMP, accompanied by members of the Hong Kong police force, simultaneously raided certain offices and homes in Chinatowns from Victoria to Trois-Rivieres, Quebec—including those of Foon Sien. The national police seized correspondence, records and other documents in search of illegal immigrants. Shock and dismay led to outrage, and Foon Sien declared, “They (the police) are checking every man, woman and child. In my mind, I think it is destruction of human rights and dignity and, to us, a loss of civil liberty.”

A month later, 22 delegates from Chinese communities met separately with Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, Justice Minister E. Davie Fulton and Immigration Minister Ellen Fairclough to learn the outcome of the raids. They were assured that no Chinese would be persecuted or deported who had helped with the illegal entry of family members. In the end, twenty-four Chinese were prosecuted, five of whom were never brought to trial, and two acquitted. Two were put on probation and the rest were fined or imprisoned or both.

Eventually an amnesty policy called the Chinese Adjustment Statement Program was implemented from 1960 to 1972 when more than 12,000 Chinese had their status adjusted.

During that time Foon Sien retired, but continued his interest in international affairs, Chinese customs, social and political problems faced by Chinese Canadians and life in Chinatown. He was, to many people, a person to seek for help or advice. In his own backyard of Chinatown he helped settle disputes and was known to have loaned money out of his own pocket to those in need.

He was an active member of not only the Chinese Benevolent Association but of the Wong Kung Har Society, the Chinese Canadian Citizens Association, the Chinese Trade Workers Association and the Liberal Party, Vancouver Centre branch. He was a founder and board member of the Vancouver Civic Association, the forerunner of the B.C. Human Rights Council. He had a membership in the Canadian Council of Christians and Jews and the Vancouver Citizenship Council where he served as a Chinese community representative on the B.C. Ethnic Sub-Committee. .

Newspaper columnists called him the “unofficial Mayor of Chinatown.” He was also termed “Champion of Chinese Rights” but the “mayor” label stuck, an indication that Foon Sien spoke with a single voice for Chinatown.

When he finally retired from the Chinese Benevolent Association in 1960, Foon was satisfied that the government had finally relaxed the immigration policy. He said, “Our idea was to ask the government to put a more humane concept into its immigration laws to allow Chinese to enter Canada on almost the same terms as European immigrants. This is not the same as asking for complete equality. We do, however; feel that relatives of Chinese Canadians such as direct descendants should be allowed into the country irrespective of age.”

In the October 18, 1961 issue of Chinatown News, columnist Bill Kan gave credit to Foon Sien for: “… the following tangible results: (1) the restoration of the Canadian citizenship rights to Chinese Canadian females who lost those privileges through marriage (2) readmission to Canada for all those belonging to this category together with their husbands and children under 21 (3) permission of parents of Chinese Canadians over 65 to take up residence in Canada, and (4) entry of mail order brides. Through these improved laws, thousands of Chinese Canadians were able to join their families and take up residence in Canada today, thanks to a tenacious fighter named Foon Sien.”

Foon Sien’s constant lobbying kept the government in check and reminded them that the immigration policy did not treat Chinese immigrants equally and fairly. Chinese immigration dropped in numbers when he retired in 1960 but his persistence laid the groundwork for the formulation of the Immigration Act of 1967 based on the point system.

The new Act ended the explicitly racist immigration policy, and with its point system ranked independent immigrants according to age, education, labor skills, language skills and resources in a fair and equitable manner much as Foon Sien had wanted.

In his lifetime he was a recipient of many awards. He died July 31, 1971 and his funeral was one of the largest seen in Chinatown.

![Chinatown [Image: Vancouver Courier]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/chinatown-800x445.jpg)

![Foncie Pulice [Image: Vancouver Sun]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/8484241-390x205.jpg)