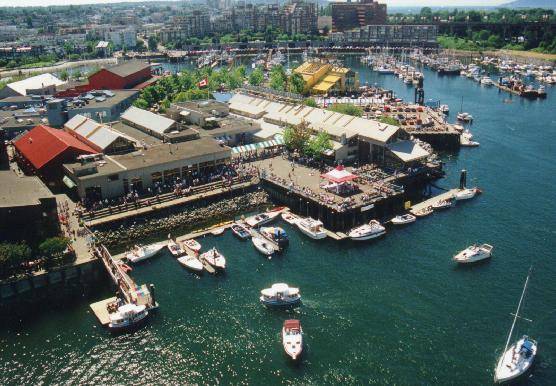

Granville Island

The 38 acres of Granville Island, worth many millions of dollars today, were once a little mud flat worth zilch. The little mound, in fact, used to disappear at high tide. But, to a keen-eyed public official named Sam McClay, that drab little mud flat (some called it a sand bar) under the shadow of the old Granville Bridge looked as if it might be a good base for some landfill. McClay was secretary of the Vancouver Harbor Commission during the early years of this century and a strong advocate of the creation of new—and cheaper—land. A land boom had begun in Vancouver in 1905, you see, and land became so costly (especially if it had access to the waters of False Creek or Burrard Inlet) that many manufacturers couldn’t afford to locate at suitable sites; they had to go to less desirable areas.

[Photo: Maurice Jassik, www.seegranvilleisland.com]

Just as McClay’s plan to expand the mud flat was about to be put into effect, a depression came along and the money needed for the job was no longer available.

Until, that is, a few years later and the arrival of Harry Stevens on the scene. Stevens, 28 at the time, was a Vancouver alderman, a man of boundless energy. (He went on to become a Conservative MP, a cabinet minister under Meighen and Bennett, and the leader and sole parliamentary representative of the short-lived Reconstruction Party before he returned to the PCs. In 1952-53 he was president of the Vancouver Board of Trade.) Stevens began a campaign to persuade Ottawa to develop the mudflat into an island, the new property to be under federal control. He succeeded: In 1913 a contract was awarded to the Pacific Dredging Company and work began. Developed under the direction of the Harbour Commission, the island was divided into 80 lots generally 50 or 60 feet (15 or 18 metres) wide and 200 to 300 feet (61 to 91 metres) deep . . . the entire creation of the island worked out to a cost of $600 an acre! It was described by the commission as “the cheapest reclamation work in the harbour.” (As an indication of change, note that the Granville Island sea wall completed in 1977 cost an average of $960 per lineal foot)

The total price for the island and its services—sewage, water, and a BCER spur line—was $342,000.

The first tenant, the B.C. Equipment Co., got a lease and began to build on its lot in June of 1917. A report issued in the early ’30s showed there were 40 tenants (who almost totally occupied the island) and they were paying an annual rental equivalent to $1,600 an acre.

The original area of the new island, built from fill sucked up from the bottom of False Creek (and perhaps English Bay), was 34.28 acres. This was later increased to the present 38 when a bridge to the island was dismantled and extra fill was put in to join the island to the Vancouver “mainland.” (I’ve seen figures of 37.04, 40, 41 and 42 acres for the island, but a recent aerial survey indicates 38 is correct.)

Locals used to call it Mud Island; it wasn’t until about 1938, apparently, that the name Granville Island began to be used regularly.

In June of 1973 the ownership of the island was transferred from the National Harbors Board to Central Mortgage and Housing, now Canada Mortgage and Housing. In March of 1977 MP Ron Basford and Vancouver mayor Jack Volrich officially opened the Granville Island sea wall, and Basford said it marked the transition of the island from a “somewhat dishevelled industrial area” to an area oriented toward people. The total redevelopment cost $19.5 million (to buy up leases, put down sewers, lay underground wiring, build the sea wall, and so on), but most of the island’s old industrial buildings have been retained.

Today, Granville Island is one of the city’s most delightful places to visit . . . and we do, in the millions. Some 10.5 million people visit annually now, and many of them go to the Granville Island Public Market, a great urban experience.