The Orpheum

The entrance is deceptively narrow. A dozen casual steps along Granville Street and you’ve gone by. But millions have not always gone by, they have gone in.

For nearly 80 years the Orpheum has been luring showgoers in—millions upon millions of them. They have walked through its richly ornamented concourse, up its sweeping carpeted staircases, past opulent wall decorations and tall columns and into the great domed auditorium where nearly 2,800 seats curve in great arcs beneath a huge and beautiful crystal chandelier. Surrounding the chandelier, a sprawling, colorful ceiling mural celebrating the musicians and other performers who have strutted their stuff on this gorgeous theatre’s stage.

They don’t build them like this anymore.

In one of the great rescue operations of the last century, the people of Vancouver came to the defence of the Orpheum when the grand old entertainment palace was about to be gutted and turned into a hive of smaller movie houses.

Now the people own it, and it is a treasure. In fact, it has been designated a National Historic Site.

You’ll learn more about that treasure when The History of Metropolitan Vancouver is published in 2009—and about the gifted man who created much of it. He was architect Marcus Priteca, a Scot who revolutionized theatre design in North America, devising a style that was, in truth, an extravagant melange of styles, borrowing from a dozen traditions and creating buildings that, in some cockeyed and wonderful way, work. Spectacularly.

Among the cast of characters in the Orpheum’s story is the showy Joseph Langer, a Vancouver businessman who was able in 1927 to pony up $1 million to build the Orpheum—and who was in deep financial trouble three years later. The cast also includes artist Anthony T. Heinsbergen, who gave the theatre much of its colorful uniqueness in design in 1927, and then came back 50 years later and did it all over again.

A battalion of famed vaudeville performers danced, sang, capered, joked and made magic up there on the Orpheum’s stage. There were convulsive changes to their world initiated by the “movies,” changes that threw an entire generation of performers out of work at the same time they opened up vast, and vastly rewarded, opportunities for a new breed of entertainer.

As important as anyone to this astonishing theatre is the astonishing Ivan Ackery, the theatre’s manager for decades and a promotional genius, a man who could pack this big house even for movies that didn’t deserve such audiences.

Every room in this multi-roomed entertainment palace has a history: there’s Ackery’s old office where he dreamed up his promotional stunts and where the sink was damaged by Frank Sinatra (practising his golf swing); over there was the “animal room” where elephants and trained dogs and seals and snakes and tropical birds once waited their hour upon the stage; behind that nondescript door is the mighty Wurlitzer organ that purred and hummed and thundered accompaniment to a myriad of entertainment attractions, and is even now the focus of another rescue campaign; in the upper reaches of this cavernous building is a “symphony rehearsal hall” where no symphony ever rehearsed. Down those aisles, her flashlight glowing to guide movie-goers, once walked young Orpheum “usherette” Yvonne De Carlo who, a few years later, would be a star up on its big silver screen.

Norman Young, the retired theatre arts professor who for years conducted tours through the theatre, always points out the jaw-droppingly intricate and beautiful (and big) Czechoslovakian crystal chandelier suspended above the heart of the auditorium and tells of the hotel that offered $65,000 for it and was turned down. (He’ll also, with somewhat less enthusiasm, point out the ornately painted blank spots on the theatre’s colonnade walls where four mirrors once hung—until they were stolen.)

All around the theatre, on every floor, are ornamental grace notes—murals, paintings and other art work, decorated wall fabrics, tiling, fancy balustrades, gilded mirrors, ironwork, ornate chandeliers, sconces, corbels, tapestries, plush carpeting, varied and exotic architectural embellishments—a never-ending feast for the eye.

And, above you and below, all the hidden mechanisms that make it work: the ropes and wires and counterweights, lighting appliances, control panels, speaker systems, rehearsal rooms, storage spaces, catwalks—and all the men and women in the building who labor, most of them unseen, to make it all happen.

And, unseen but present all around you, a million memories: of slapstick comics, and dewy-eyed soubrettes, nimble magicians and world-famed musicians, wise-cracking jugglers and sweaty acrobatic teams, standup comedians and dignified divas, and the fabled names of the movies: Garbo, Gable, Bogart, Bacall, Hepburn, Monroe, Olivier, Gielgud, Gary Cooper, Burt Lancaster, Bette Davis, Jack Benny, Alec Guinness . . .

This is a great building, with a long and colorful history.

For theatre goers themselves the Orpheum’s history began with a “soft” opening on November 7, 1927. The official opening was the next day.

Daytime admission for its 1,800 seats was 25 cents, children 15 cents. You could reserve a seat for 40 cents. Besides a movie—perhaps accompanied by the mighty Wurlitzer pipe organ—your 25 cents got you a vaudeville show. Prices doubled in the evening.

What were wages like at the time? Well, a newspaper advertisement of the time seeking an “organist and choir leader” offered $20 a month; lathmill men were wanted for 40 cents per hour “and better”; someone in Point Grey (still a separate municipality) advertised for a “Capable girl, help housework, one used to children, $15 a month, sleep in, other help kept.” So an evening ticket at the Orpheum would have cost that “capable girl” a full day’s wages.

Overcoats were on sale at Claman’s, normally $29, going for $19.50. A man’s suit was $27 at the Hudson’s Bay. A new electric gramophone did away with the need to wind the machine. It cost $230. The winding kind were $190.

There was an ad for Thanksgiving Day on “the top of the world at Grouse Mountain.” A full course turkey dinner up there was $1.50. Bus to go to Grouse and back: $2.50.

The Province reported that a total of 9,000 people had enjoyed the three shows put on at the Orpheum that Monday, running continuously from 1:00 to 11:00 p.m. What they saw and heard was a mix of vaudeville, music and a movie. “Tributes of admiration were heard on every side,” the paper reported, “and Vancouverites bore themselves (as they trod on the heavy-piled carpets and were bowed to their seats by trim damsels in smart costumes and men ushers with naval rankings on their sleeves) as to the manner born. Their manner plainly said they had been used to this sort of thing all their lives and had always entered vaudeville and picture houses via noble staircases, under magnificently jewelled chandeliers and handsome corridors adorned with well-chosen works of art, with palms and flowers and well-cushioned seats . . .”. The lavish surroundings, in fact, created traffic problems during the theatre’s first days as people leaving one show wandered around admiring the new building and getting in the way of people coming in for the next.

There were five acts of vaudeville, and a movie, The Wise Wife, with Phyllis Haver. For the record the vaudeville acts included a musical performance by Marie White and the Blue Slickers (one star being Jack Howe, “King of the Kazoo”); Pat Henning and Co., a family act, in Versatility; the “Beloved Clown Toto”; dancers Chaney & Fox; Ethel Davis “in Refreshing Song Chatter” and Bee Hee & Rubyette.

There was a Pathe newsreel, too, and although we don’t know what 1927 events were covered in it, there were lots to choose from: Chiang Kai-shek had taken Hangchow, Shanghai and Canton; U.S. President Coolidge announced he wouldn’t run again; there was the already mentioned Lindbergh flight; the fossil remains of Peking Man were discovered; Ford’s Model A was introduced; the first U.S. demonstration of television was given; dancer Isadora Duncan died; Babe Ruth hit 60 homers, a record that would stand for 30 years . . . and the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa reopened (they had been destroyed by fire in 1916)

The theatre was packed to capacity for its three shows the next day, Tuesday, November 8th as well, but this was the formal opening and now there were dignitaries on every hand. The ceremony ran from 7 p.m. to 11. Vancouver’s trim little mayor, Louis D. Taylor, congratulated Bill Barnes, the new theatre’s manager, and the Orpheum Circuit for its faith in the future of the city. Mary Ellen Smith, the first woman to become an MLA in British Columbia (she represented Vancouver) and the first in the British Empire to be a cabinet minister, delivered an “appreciation” of the new theatre on behalf of the women of the province.

Many of the invited guests had names that will be familiar even today to long-time residents of the city: Lieutenant Governor Randolph Bruce was there, and so was William Sloan, the province’s acting premier. The mayor of New Westminster, Wells Gray, was on hand with his wife, as was Vancouver’s chief of police, Walter Long and Mrs. Long, and the chief of its fire department, John Carlyle and his wife. R. J. Cromie, who had founded the Vancouver Sun 15 years earlier, and had since absorbed the News-Advertiser and the World and Mrs. Cromie rubbed shoulders with famed journalist Roy Brown and his wife.

In the midst of this glittering array of Vancouver’s upper crust was one Joseph F. Langer, financier, whose smile may have been the broadest of all. It was this flamboyant gentleman’s money—$1 million of it—that had been used to build the magnificent new theatre.

You’ll learn more about the theatre and its people in my book.

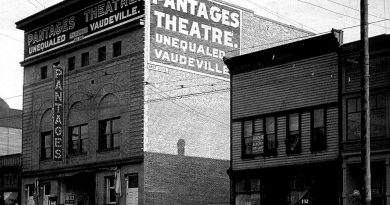

(By the way, the photo of the Orpheum accompanying this article can be dated to 1946. The movie Meet the Navy, a filming of a wartime revue produced by the Canadian navy, was made that year.)