A Stainless Steel Streamliner

![The book, Westward Across Canada, published by Canadian Pacific

[Image: AbeBooks]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/613849036.jpg)

published by Canadian Pacific

[Image: AbeBooks]

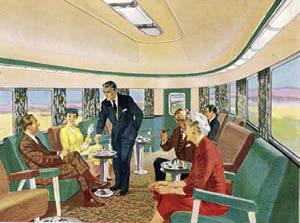

A new era in rail travel in Canada began April 24, 1955. The Canadian Pacific Railway introduced The Canadian, an “ultra-modern, lightweight, highly attractive stainless-steel streamlined train.” The train would offer the world’s longest dome ride: 2,881.2 miles. (4,637 k/m).

Postwar Canada believed passenger train travel had a healthy future, so Canadian Pacific met the demand by introducing this fancy new service. There were two dome cars (there should have been more), a handsome dining car with excellent food, and a variety of sleeping arrangements: roomettes, double bedrooms, a drawing room, berths and more.

The last car of each train-known as the Park car-became the most well known. The car had a rounded-end observation lounge, a beverage room with the dome level above it, and first class sleeping space made up of a large drawing room and two bedrooms. Each car was named for a National or Provincial Park. The beverage room featured original murals by Canadian artists, some of whom were members of the Group of Seven. The example shown here is titled Eutsuk Lake. Painted by Edward John Hughes, it graced the wall of the car Tweedsmuir Park, named for the BC Provincial Park where you would find Eutsuk Lake.

The Canadian was faster than the existing Dominion service: Running time from Vancouver to Montreal was just over 71 hours. The Dominion, which continued running until 1966, made many more stops, taking almost 85 hours.

Engineer R.J. McQuarrie pulled his 14-car train out of the CPR’s Cordova Street station at 8:00 p.m. Sunday, April 24. There were just over 300 passengers aboard, and a crew of 22. At 1:00 p.m. Montreal time on the same day the westbound Canadian left for Vancouver. (There could be as many as six Canadians in service at once.)

The Canadian was known for the fine food served in its dining cars. For breakfast, scrambled eggs cost 75 cents, a pot of coffee was 30 cents. For lunch or dinner you could have a sirloin steak ($3), and a great apple pie for dessert (30 cents.)

Not until I talked to train buff extraordinaire Jim McGraw did I learn of the CPR’s “ice breakers.” You can plainly see them in many of the photographs in a 1986 book called The Canadian, by James W. Kerr. They’re stiff metal projections sticking up from the roofs of the railway’s locomotives, designed to knock off icicles that formed on the ceilings of the line’s many tunnels! That feature was necessary to protect the forward-facing windows of the dome cars.

Ironically, the Canadian‘s sleek stainless-steel cars had been inspired by an American train, the California Zephyr, and were built by an American firm, the Budd Company of Philadelphia. Many of the components, however, were made in Canada. (The cars were very well built: “Amazingly,” says Jim McGraw, “the stainless steel cars built by Budd in 1953 and 1954 for Canadian Pacific Railway, are still running off the miles more than 50 years later!”)

The Canadian was responsible for a spike in the number of train travellers, but, sadly, it was short-lived. Today, VIA Rail-which took over the service in 1978-runs the Canadian just three times a week (and on CN rails). And a trip that cost $77.85 in April of 1955 (one-way coach Vancouver to Montreal), when the average weekly wage in Canada was $61, will set you back about $730 today.

The average weekly wage in B.C. for a 40-hour work week these days is $780. So in 1955 it would have cost you somewhat more than a week’s wages to make that journey, somewhat less to make it today. All aboard!

![The trans-continental train, The Canadia. [Image: Derek Low]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/6-3-700x445.jpg)