Collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge

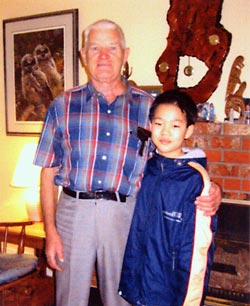

In 2004 Eric Daichi Ishikawa, one of the students taking part in that year’s Historica event (in which students from elementary schools all across Canada prepare historical exhibits on topics of their choice), assembled an illustrated report on the June 17, 1958 collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge. Daichi was a student at Edith Cavell Elementary in Vancouver. It’s a superb production, made all the more remarkable by his age: 10.

He gives the history of the first bridge (1925) across that point on the Inlet, a bridge so badly placed it was hit many times by ships and in September of 1930 was put out of commission for more than three years when a ship took out the centre span. (The refigured bridge—the centre span was moved farther out over the water—is in use today as a railway crossing.)

The decision was made in 1955 to construct a new bridge, a six-lane high-level highway bridge, budgeted in April, 1955 at $12 million to $15 million, with a construction time of three years. “It was to be the longest cantilever bridge in Western Canada,” Daichi writes, “the eighth longest in the world.” Its length was 1,292 metres (4,238 feet.) He walked across it and back with his family. It took him 40 minutes. “By car at 80 km per hour, you would take about 1 minute to cross the bridge.”

What makes his report particularly outstanding is the interviews he conducted with some of the survivors. On February 28, 2004 he visited Lucien Lessard, then 76, at his home in Langley. Lessard was a 30-year-old foreman in 1958.

Daichi: First of all, how did you survive?

Lessard: When the bridge came down, I fell in the water on the side of the bridge, so I didn’t hit any of the structures on the bridge. I was lucky. When I came out, I grabbed some floating planks and managed to see, floating until somebody on a boat picked me up to put me to the shore . . .

Daichi: Were you one of the twenty people who got injured and sent to the hospital?

Lessard: Yes. When the bridge collapsed I broke my arm and my leg and hurt my back and my face, and I got all my intestines mixed up because when you drop 200 feet and hit the water you get hurt, right? I might have passed out and ended up on the bottom of the ocean. Steel is heavier than human beings. The bridge was coming down faster and we were coming down slower. When I hit the bottom, the steel was already on the bottom. It was dirty and black, so I could see nothing . . . I managed to work my way up and tried to pick a plank, but I found out I had a broken arm and a broken leg, so I managed to get a plank and float for a while until somebody picked me up and brought me to the shore.

Daichi: That was a big disaster. You’ll never forget this.

Lessard: I’ll never forget that. That’s why I feel there’s an obligation for me. That’s why I’m doing this with you. Only a few of us left alive now. I’m seventy-six years old. I’m an old man. I’ve got only a few more years to live. So any time I have a chance to help out our new generation, I think I’ve got an obligation to do it . . . There are only five survivors left alive now, and only two or three of us can walk.

Daichi: I’m really glad you’re one of the lucky ones.

Lessard: I’m very fortunate. That’s why I appreciate my life now. I’ve been in a good life. After the collapse, I was in hospital for five months. I was a lucky one who survived.

One of the interviews Daichi conducted was with Patrick Glendinning, who was a child at the time, and whose father Colin—severely injured—was one of the survivors.

Daichi: Did you actually go and see the disaster?

Glendinning: Not at all. As kids, even when they were rebuilding it, we never ever went to the site. But Dad went back on the bridge 6 months later. He had a broken leg, right? So it healed and then a year later, when they were rebuilding it, same day, same month, he broke his leg again. He got treated by the same nurse and the same doctor at the same hospital . . . Everything else was the same except it was the opposite leg!

Incidentally, Glendinning’s wage at the time was $3.85 an hour.

Daichi includes newspaper clippings, news shots of the collapsed span, photographs that illustrate different types of bridges, photos of himself and his family on the bridge, and much other supporting material. It’s a terrific piece of work.

![The Royal Party [King George VI and Queen Elizabeth]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/f28034b5-2600-4dec-916a-6a68073057ad-CVA289-005.463-390x205.jpg)