O Canada!

Was Canada’s national anthem written in Vancouver? No.

To get the facts, come back with us to a gloriously sunny day in July, 1908 in Quebec City.

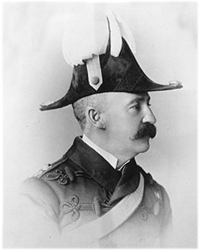

Brigadier-General Lawrence Buchan (left) was in command of the garrison at Quebec, at the head of 12,000 troops taking part in ceremonies marking the 300th anniversary of the city’s founding. The Prince of Wales (later King George V) was reviewing the troops.

At one point the massed bands of the garrison played a stirring, patriotic air composed in 1875 by Quebec’s Calixa Lavallee (right). The prince was so impressed by it that he asked, “What is that magnificent composition?” He was informed that the piece had no formal title and was known simply as “Chant Nationale.” (Note that this was 33 years after the tune’s composition.)

Lawrence Buchan was impressed with the music, too. He got a copy of the sheet music, which included the French lyrics by Adolphe-Basile Routhier (sung to this day by Canadian Francophones), and had them translated into English. He sent them to his brother, Ewing Buchan, then manager of the Bank of Hamilton in Vancouver. Ewing Buchan was very taken by the air and he and his family often sang it in their home at 1114 Barclay Street. Daughter Olive provided the piano accompaniment. But Buchan was dissatisfied with the English translation of the French words to the tune and decided to write his own, a single stanza.

The opening four notes suggested to Buchan an obvious first line: “O Canada.”

The same two words began the French lyrics to the song. The air’s first four notes, in fact, inspired a small mob of Canadians outside Quebec to begin their versions of the song with the same two words. But it must be said that not all the lyrics were inspired by pure patriotism: it seems a Toronto-based magazine, Collier’s, an offshoot of the American publication, had offered a prize for the best three-stanza song in English, set to the Lavallee air.

It gets confusing here: The Canadian Encyclopedia of Music, in a long article, says: “The winner, announced August 7, 1909, was Mrs. Mercy E. Powell McCulloch, one of some 350 competitors. The English version most widely used, however, is the one by Robert Stanley Weir, published in November 1908 . . .”

It is Weir’s words, with recent modifications, we sing to this day.

Ewing Buchan (left) hadn’t known about the Collier’s contest but, says his son Percy, he would have felt no urge to enter if he had. “Having fallen in love with the beauty of the music, he had a conviction that his fellow citizens would likewise respond to the spirit of the air and would sing it if they had appropriate words.”

In 1947, at the urging of Vancouver’s city archivist Major J.S. Matthews, Percy Buchan wrote a pamphlet on his father’s creation of those now forgotten lyrics.

“It happened,” Percy wrote, “that in 1908-09 my father was second vice-president of the Canadian Club of Vancouver. The custom of the club was to open its luncheon proceedings with a toast to the King (Edward VII), followed by singing of the National Anthem, God Save the King, and to close with the first verse of The Maple Leaf Forever. Having O Canada in mind, he resolved to urge its substitution for The Maple Leaf Forever at all functions of the club and to that end devoted a considerable part of his leisure during the winter evenings of 1908 to quiet reflection on the matter.”

In the spring of 1909 Ewing sent the nine-line result to his brother in Quebec. Lawrence Buchan and a friend, Brenton A. MacNab of the Montreal Star, made a few minor changes, then Lawrence ran off a number of copies on small printed slips. He sent some to Ewing in Vancouver. A brief introductory paragraph stated that the words of the verse were the work of Ewing Buchan, rearranged by MacNab and Lawrence Buchan.

In the fall of 1909 the two brothers met for the last time in Vancouver, Lawrence Buchan contracted pneumonia during his western trip and died at 62 in October, a short time after his return to Montreal. “This event,” wrote Percy Buchan, “was a severe blow to Ewing and resolved him to bestow the entire credit for the Buchan version of O Canada on the general as a memorial in the minds of the Canadian people. That is the reason the stanza must forever bear the name of Lawrence Buchan.

“The song,” Percy continues, “had its introduction at the close of a luncheon meeting (of the Vancouver Canadian Club) on Wednesday, February 9, 1910, in old Pender Hall, situated on the upper floor of the present two-storey building at the southwest corner of Pender and Howe streets. [Remember he’s writing this in 1947.] After some brief introductory remarks by Captain William Hart-McHarg, a quartette, accompanied by Miss Grace Hastings at the piano, led the first singing of O Canada by a Vancouver audience and the first performance of the Buchan version within the Dominion . . . Eventually it became the custom of the club to close its meetings with the singing of O Canada instead of The Maple Leaf Forever.”

Ewing destroyed from his private files every trace of his authorship of the verse. But a letter to Percy from the general, written a few months before he died, makes it clear where the major credit lies.

Supporters of the Buchan version distributed some 40,000 copies to Vancouver school children and kept up steady efforts on its behalf for years. By 1929 the fight between the two factions, one pushing for Buchan’s words, the other for Weir’s, broke into print. (Some backers of the Buchan version referred to the competitive lyrics as “the Weird version.”)

Then Prime Minister W.L. MacKenzie King, visiting the coast, heard the Buchan version sung at a meeting of the Vancouver Board of Trade . . . and liked it a lot. Better than all the others he’d heard, in fact. That really got the fur flying.

Which version would prevail?

Well, this is one story to which every Canadian knows the end. But, for the record, here are the words to “the Buchan version” of O Canada:

O Canada, our heritage, our love

Thy worth we praise all other lands above

From sea to sea, throughout thy length,

From pole to borderland

At Britain’s side, whate’er betide,

Unflinchingly we’ll stand.

With heart we sing, “God Save the King”

“Guide thou the Empire wide,” do we implore

“And prosper Canada from shore to shore.”

![Board of Trade Luncheon, Hotel Vancouver [Aug. 19, 1949]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2c2eae1f-1857-4e74-8fe2-5dd67b00689c-LEG1701.1.jpg)

![The trans-continental train, The Canadia. [Image: Derek Low]](https://vancouverhistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/6-3-390x205.jpg)